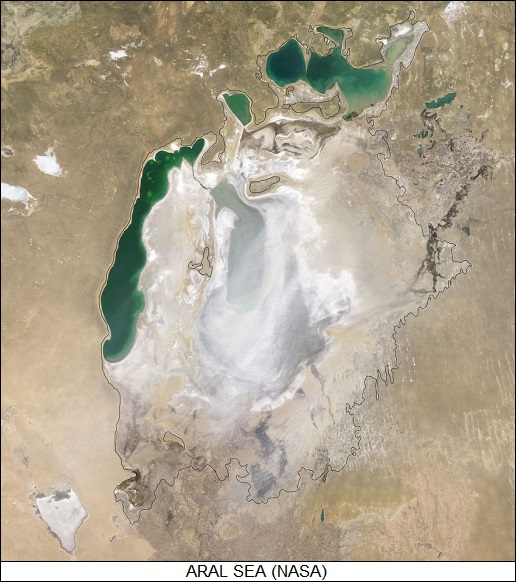

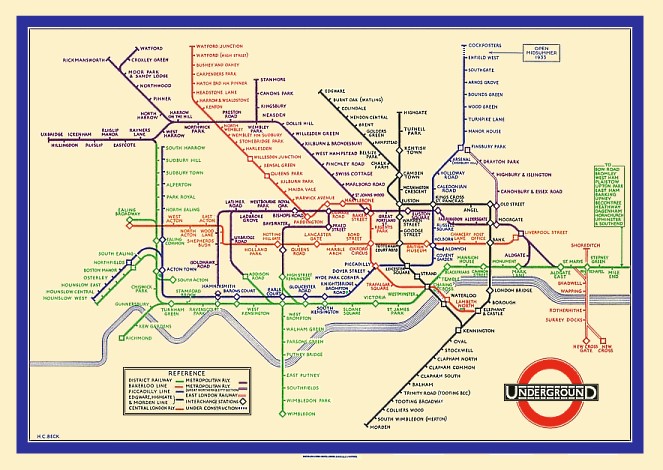

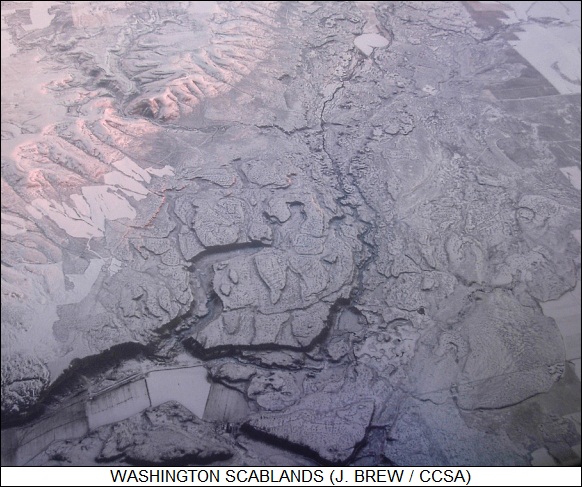

* 21 entries including: Dawkins' THE BLIND WATCHMAKER, global water supply, the Black Death, resurgent volcanic calderas, 1918 flu deciphered, figuring out crowd crush, supercapacitors, banana horticulture, battle of Palmdale 1956, Afghan opium, virtual machines against digital decay, Japans rises, Democrats be careful, underground coal fires, London Underground map, Dick Feynman, Bretz floods, and suburban wildlife problems.

* THE BLACK DEATH (1): As discussed in an article from some years back in SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN ("The Bubonic Plague" by Colin McEvedy, February 1988), in the year 1346, Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East had a population of about 100 million people. By 1352 a quarter of these people were dead, struck down by a wave of pestilence, caused by bubonic plague. The outbreak from 1346 to 1352 became known as the "Great Dying" or the "Great Pestilence", but it has come down through history as the "Black Death".

The plague had swept through Europe during the reign of the emperor Justinian, 800 years earlier, with milder recurrences for the two centuries after that; similar recurrences occurred for four centuries after the Black Death. The disease has not been a major health threat since then, though it still occurs infrequently in many parts of the world.

About three-quarters of those infected by bubonic plague during the Black Death died from it, usually within about five days. One of the early signs of the disease were the "buboes" that gave the disease its name: gross and painful swellings of the lymph nodes in the armpits, neck, and groin. Three days after the appearance of the buboes, victims were generally struck down by high fever, becoming delirious, and afflicted with black splotches from hemorrhaging under the skin. The buboes continued to swell during the course of the disease, and if the victim lived long enough, they would burst, causing agonizing pain. That was actually an encouraging sign because it meant the victim was still putting up a fight; half of those who died were gone before this phase.

The disease appeared in two forms. In "septicemic plague", the victim's blood was infected directly, leading to massive hemorrhaging, septic shock, and rapid death. In "pneumonic plague" the victim's lungs were infected, leading to quick collapse and death.

Nobody had any clear idea of what caused the Black Death. People were inclined to think of it as the consequence of unfavorable astrological combinations, or "miasmas" -- malignant vapors in the air. There were more paranoid explanations. Some believed that it was the result of spells cast by evil witches. Some Christians believed it was caused by poisons spread by Moslems, and some Moslems believed it was caused by poisons spread by Christians. Some Moslems and Christians blamed the Jews; in some cases, Jews were burned alive in their houses. It is to some credit of the Church, noted in medieval times for persecution of the Jewry, protested against such pogroms. The pope, who was corrupt but not inhumane, protested that the Jews were suffering as badly from the disease as the Gentiles and so were unlikely to have been its authors.

* The disease remained mysterious until 1894, when the French bacteriologist Alexandre Yersin discovered the cause, a rod-shaped bacterium that became known as Yersinia pestis after him. This bacterium infects wild rodent populations around the world, with the infection transmitted from one rodent to another through fleas.

The rat and its associated fleas were the primary disease vectors for the Black Death. If a flea bites an infected rat, the plague bacteria multiply in the flea's gut until it cannot digest blood any longer. The flea then goes wild, biting continuously in a futile attempt to obtain sustenance. This helps spread the infection through the host rat, which then normally dies. The flea then moves on to another host. If the fleas can't find another rat, they attack other hosts, such as humans and their domesticated animals, which lived in close proximity to rats in medieval times. Humans could sometimes pass the disease to one another from the inhalation of infected respiratory droplets, but otherwise the plague was not particularly contagious as such. Once the rodents died off, so did the plague. [TO BE CONTINUED]

NEXT* THE BLIND WATCHMAKER (2): Most critics concede the truth of simple examples of evolution such as the emergence of antibiotic resistance, but call them "microevolution". They insist it is a jump to think that modern evolutionary theory could account for all the elaborations of forms cited by Paley, or "macroevolution". There are those who simply refuse to believe it, claiming that there is no way organisms could spontaneously achieve such levels of elaboration. Some suggest that the only way macroevolution could happen is by supernatural means -- "supernatural" very literally meaning events not known in the rules of nature as we have observed and understand them.

Dawkins points out bats as an example of this seeming design elaboration. Many (though not all) bats rely on sonar for navigation, in which a sound is emitted and its echo then heard to range and identify an object. Radar works on the same general concept, though it uses radio waves instead of sound. The interesting thing is that bat sonar has so many technical similarities to human radar.

For example, if a jet fighter is operating a radar to search the sky for an opponent, it sends out radio pulses on a fairly long interval -- what radar engineers call a "low pulse repetition frequency (PRF)". This allows a pulse to go a long ways before a second pulse is sent out, giving the radar more range. If a target is identified and locked, the PRF jumps up drastically, allowing the target to be "seen" in more detail and tracked closely. The common brown bat Myotis will chirp at a rate of about 10 times per second when searching for insects, but this rate will go to 200 times a second when an insect is spotted.

Similarly, a radar usually has a single antenna for both transmit and receive. Since the radio echo is faint, the receiver is sensitive and the powerful transmit pulse will tend to fry it. The trick is to use a "diplexer" that shuts off the receiver path while the transmit pulse is being sent. The Myotis bat has sensitive ears to pick up its ultrasonic chirps; a special bone mechanism shuts down the ear channels while a chirp is being emitted.

* There are several other ways in which bat sonar strongly resembles human radar systems, but these two examples get the point across. Is it even possible to imagine that something so sophisticated could arise by natural selection? Of course, if provable small changes can occur over a short period of time -- or maybe even not so small, such as the transition from wolf to pekinese -- then it's not unreasonable to think that many small changes over a long period of time could add up to big changes. Besides, what is improbable over a short period of time will become a certainty over a long period of time: if we didn't age and were indestructible, then we could expect to be struck by lighting every rare now and then.

The critics use the failure to observe macroevolution in action as the basis for their accusation of the non-falsifiability of MET. Of course it isn't possible to observe it in action, because it would require observation over millions of years. Advocates reply that this is willfully setting the bar of truth to an unrealistically high level -- like insisting that astrophysicists know nothing about how stars work because they can't build a star, and claiming that small-scale experiments in particle accelerators are irrelevant. If modern evolutionary theory isn't science, then neither is astrophysics.

Certainly, it seems arbitrary to say that MET works up to a certain level, but then stops abruptly at a certain level -- with the level being conveniently adjusted higher as the evidence becomes more substantial. Dawkins created an interesting computer simulation that suggests just how powerful the force of natural selection really is. To simplify the discussion, consider my name spelled as follows:

GREG GOEBEL

That string consists of 11 characters, including a space. If I were to write a computer program to simply throw together characters and see if the result matches my name, how long would it take to come up with a winner? Given 26 capital letters and a space character, the number of possible strings of 11 characters is 27^11 = 5.56E15. Assuming that a computer could generate and test a million strings a second, going through the entire sequence, which would be the worst case for finding my name, would take over 175 years. For every character added to the string to be searched for, the time would increase by a factor of 27.

Now let's try another approach as follows:

It converges to an answer in less than a minute. Even if it were an hour, which I wouldn't think for a second, what's that compared to 175 years? This is what is known as a "genetic" algorithm, and it's nothing more than a crude simulation of a selection process -- natural or artificial, it works as well either way. This is a toy example, but the US National Aeronautics & Space Administration (NASA) wrote a genetic program to determine the optimum design for a small radio antenna, ending up with a piece of bent wire that looked like something a hopelessly bored schoolkid would make out of a big paper clip.

It is certainly very improbable -- to be precise, 1 chance in 5.56E15 -- that a computer program would be able to throw together combinations of 11 characters and come up with the string GREG GOEBEL. It is straightforward for a computer to make small changes at random, test them, and quickly converge on the answer. Engineers call this a "cut and try" design approach. Dawkins takes the concept farther, writing a program to create animal-like graphical designs he calls "biomorphs", and observes their explosion into a range of forms as the program cycles on.

In any case, Dawkins' "weasel program" has become a classic simple example in evolutionary science, and to no surprise it has been endlessly criticized One criticism is that it actually represents a model of artificial selection, not natural selection, because it works toward a prespecified goal. Actually, Dawkins pointed that out to begin with, saying the program was "misleading in important ways", most significantly in that it did work towards a prespecified goal, while evolution does not. The weasel program was never intended to be a realistic model of evolution; its purpose was simply to demonstrate the power of a selective process over random assembly -- the bogus "monkeys blindly pounding on typewriters" model of evolution.

More sophisticated programs have been created following the weasel program that model evolution much more accurately, but the critics remain unsatisfied and have come up with more criticisms -- one of the most popular being that the weasel program (and other evolutionary simulations) prove the work of a designer in nature, because the programs are designed themselves.

This sounds plausible for a few seconds -- until it is realized that it's simply reasoning by analogy, with no evidence to show the analogy is valid. This kind of reasoning is confusing a representation of a thing with the thing itself, and ends up being something like the old cartoon of painting a tunnel mouth into the side of a mountain -- to having a train come thundering out. Any natural process, like a hurricane, can be simulated, but nobody could sensibly say that means hurricanes are a complete mystery to science that can only be explained by the action of a Designer. Humans can make fires; that hardly implies that fires are Designed, and so the sciences cannot account for them. [TO BE CONTINUED]

START | PREV | NEXT* 1918 FLU DECIPHERED: As discussed in an article from AAAS SCIENCE ("Resurrected Influenza Virus Yields Secrets Of Deadly 1918 Pandemic" by Jocelyn Kaiser, 7 October 2005), in 1918 and 1919, an influenza pandemic swept the globe, killing tens of millions of people. The 1918 flu was extremely virulent and destructive, reducing the lungs of victims to what examiners described as something like "red currant jelly" and, bizarrely, killing people in their prime much more readily than the sickly and elderly. Flu pandemics have occurred then, but the 1918 pandemic remains something of a grim benchmark, raising the specter that a new flu virus might arise that would be even more destructive. That has made the nature of the 1918 flu virus an interesting subject for researchers.

Now a collaborative team of researchers -- from the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in Atlanta, Georgia; the US Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) in Washington DC; Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City; and the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) -- have resurrected the 1918 flu virus and examined its effects. The project was begun by AFIP pathologist named Jeffrey Taubenberger in 1995. The researchers obtained tissue samples from an Alaskan victim who had been buried in permafrost. The team used the samples to reconstruct the critical parts of the eight genes of the virus, which were then replicated and spliced into modern flu genes for replication in target cells, and used on lab mice.

The effort was conducted under a high level of biosecurity -- Biosafety Level 3 (BSL-3), with additional precautions -- as well it might be: the revived virus hit the lab mice in exactly the same ferocious way it swept through human populations in 1918 and 1919. The mice died in 3 to 5 days, and were found to have the gruesome lung inflammation described by medical researchers trying, without success, to fight the pandemic.

Analysis of the 1918 flu showed that it had an unusually effective hemaggluttinin (HA) surface protein, which the virus uses to "lock on" to host cells for infection. Inserting the gene for that particular variant of HA into mild strains of flu virus made them just as nasty as the 1918 flu; splicing in other genes from the 1918 flu had little effect. However, the 1918 flu also was not dependent on host cells providing the protease (protein enzyme) trypsin to activate the HA protein before the virus was released from the victim cell. That implies that the 1918 flu was not limited to infecting trypsin-loaded lung cells.

Knowledge of the 1918 flu will help development of defenses against other violent flu strains in the future. Although there were suspicions that the 1918 flu strain was a swine flu, genetically it appears to have been a bird flu that managed to perform a species jump to humans. Understanding the specific mutations that allowed this flu virus to successfully jump to humans will help give some alert against future dangerous strains, as well as help in the development of countermeasures.

The important genetic data from the 1918 strain were published in the scientific press. There were concerns that this data might be used by developers of "doomsday bugs" to synthesize nastier biowarfare agents that could end up in the hands of terrorists, but a new US Federal review board judged that the benefits to researchers outweighed the risks. Suppressing data without leaks is difficult, and terrorists might not be too quick to make use of a virus if the ability to create countermeasures was obviously available.

BACK_TO_TOP* WALK DON'T RUN: As discussed in an article in AAAS SCIENCE ("Directing The Herd: Crowds & The Science Of Evacuation by John Bohannon, 14 October 2005), on the morning of 11 September 2001, an airliner hijacked by Islamic terrorists flew into one of the towers of the World Trade Center in New York City. Another airliner soon followed, hitting the other tower. Less than two hours after the first impact, the towers collapsed. About 500 people were killed by the impacts themselves; about 1,500 died in the collapse of the towers, because they were unable to evacuate the buildings. Things might have been vastly worse: one estimate states that if both towers had their full capacity of 20,000 people each, the casualties would have run to about 14,000 dead.

This leads to the question of how to design buildings and create procedures so such structures can be evacuated quickly. To this time, skyscrapers haven't been designed with full, rapid evacuation in mind, with regulations specifying only that the design factor in the evacuation of a few floors in response to a localized fire. That approach is now seen as inadequate.

One of the first tasks is to understand the group psychology and dynamics of crowds in an emergency. Two researchers from Monaco have been quietly filming pedestrian traffic in ten different cities around the world, trying to identify common elements as well as differences. They have found that pedestrians in London walk faster than pedestrians in New York City. One British researcher points out that even on busy dense city sidewalks, people rarely collide with each other, a group dynamic that invites further investigation.

When a panic occurs, dynamics change. For example, in an emergency everyone tries to dash for the exit. The end result is a traffic jam that prevents most of them from getting out; it turns out that the optimum speed for escape in an emergency is a brisk walk. People can become packed into a herd that flows right by marked exits. In the worst case, people will be suffocated by "crowd crush", packed together so tightly that they cannot breathe. Crowd crush can be so powerful that it will bend steel barriers, and since the victims can't breathe, they can't cry for help, so nobody realizes what is going on until it is too late. Incidentally, people are rarely trampled in such panics.

A team at the US National Institute of Standards & Technology (NIST) was ordered by the US Congress to investigate the evacuation of the Trade Towers on 9-11, while a British group under fire safety engineer Ed Galea at the University of Greenwich performed a similar study in parallel. Interviews were performed and computer models written. One interesting fact was that many people didn't try to evacuate until well after the emergency; 77% of the survivors interviewed packed up in five minutes or so, 19% took an hour, and 4% took over an hour -- people were uncertain and wanted to save their computers.

Galea wrote a computer model named EXODUS, which both teams used to model the evacuation. When NIST ran the model with the full occupancy of 40,000 people, they came up with the 14,000 deaths, mostly of people trapped in the stairwells. Nobody was surprised at this, since the stairwells weren't designed to handle that kind of traffic, and in fact no skyscraper is designed that way. NIST is pushing for new building codes for skyscrapers when they are reviewed in 2008. Builders are not enthusiastic, claiming that the 9-11 catastrophe was an event not likely to be repeated any time soon. NIST officials reply that since a skyscraper may well last a century or more, the probability of any one such structure eventually suffering a catastrophic disaster, from natural or man-made causes, is pretty high.

Obviously, even if new building codes are implemented, since skyscrapers last for a long time, we'll still be stuck with buildings not designed to those specifications. That means that over the short to mid term, the emphasis has to be on procedures and, where possible, retrofits. The evacuation rate from the second Trade Tower was much better than from the first, since the elevators were still working until the impact of the second airliner. New elevator systems can be installed that have their own power supplies and sensors so they won't open on floors where a fire is in progress. Models show that sky bridges to neighboring buildings would have also greatly aided an evacuation of the towers.

All sorts of other escape schemes have been proposed, such as external "slides" made of fabric, or sliding down exterior poles while wearing a vest with an electromagnetic braking system, or even "ballutes" -- balloon-parachutes in the shape of shallow cones -- that could pop open immediately after deployment. For the moment, however, the focus will have to be on modifying stairs and elevators, and taking fire drills much more seriously.

BACK_TO_TOP* SUPER CAPACITORS: As discussed in an article from IEEE SPECTRUM ("Super Charged" by Glenn Zorpette, January 2005), engineers at the NessCap Company in Yongin, South Korea, have a bright idea: they want to replace batteries with "supercapacitors" that can hold far more charge than any capacitors built to date. NessCap now produces a supercapacitor about the size of a soda pop bottle that can store 5,000 farads at 27 volts, and company officials think they can do a lot better. Ultimately, they want to replace automotive batteries with supercapacitors.

The idea has a lot going for it, on paper at least. Supercapacitors can provide greater power on demand, can be charged rapidly, can function at wider ranges of temperatures, and compared to batteries have an unlimited number of charge-discharge cycles. The only problem is that current supercapacitors are expensive and have energy densities -- charge per unit weight -- about 20 times smaller than that of, say, lead-acid batteries. This means that for the moment supercapacitors are only really applicable for niche applications, where their long life compared to batteries is an asset, only small amounts of electricity have to be stored, and the cost of the supercapacitor is small relative to the overall cost of the system.

Makers of high-end battery-operated stereo gear have used them to provide peak power for musical crescendos that can't be provided quickly enough by the battery itself. A particularly interesting application is in solar-powered lighting tiles that can be embedded into a walkway or staircase. The tiles acquire power during the day and use an LED to provide a safety guide at night; battery operation wouldn't last long enough to be workable. Since supercapacitors charge and discharge so fast, they are regarded as potentially ideal for hybrid-electric or fuel-cell cars.

* The traditional notion of a capacitor is two conducting plates separated by a nonconducting "dielectric", composed of molecules that can be electrically polarized. Opposite electric charges are placed on the two plates; the amount of charge is proportional to the area of the plates and the "dielectric constant" of the dielectric filler, with this constant giving how much more charge the capacitor can store than it would if there were simply empty space between the plates. In addition, reducing the spacing between the plates gives more charge storage for a given voltage.

In the early 1980s, researchers at Standard Oil of Ohio (SOHIO) discovered that if carbon granules, or "activated" carbon, were immersed in a conductive liquid solution or "electrolyte", the result was a really impressive capacitor. The reason was that the activated carbon granules had such an enormous surface area relative to their weight. Nippon Electric (NEC) of Japan signed a license with SOHIO for the technology in 1971; a decade later Panasonic of Japan picked it up in a big way, with the US Department of Energy (DOE) then performing a number of further studies.

The basic recipe for a supercapacitor is to take two metal-foil electrodes; coat them with activated carbon; sandwich a paper separator between the two foil layers; and immerse the sandwich in a liquid electrolyte -- these days, typically acetonitrile, which has excellent electrolytic properties but suffers from the flaw that when it burns, it can produce cyanide gas. Manufacturers would like to have something that works as well but is safer. Electrical leads are connected to each of the foil electrodes. If the supercapacitor is then connected to a DC voltage source, electrons will begin to accumulate on the negative electrode, while being depleted on the positive electrode.

The electrolyte provides positive and negative ions. The positive ions migrate to the carbon granules bonded to the negative electrode, while the negative ions migrate to the carbon granules bonded to the positive electrode. Although the paper separator is nonconductive, preventing the electrodes from shorting out, it is porous and ions migrate through it freely in both directions. The result is a thin capacitive layer on each carbon-coated electrode, and so supercapacitors are sometimes called "double-layer capacitors".

Few of the processing steps for building a supercapacitor are trivial. Obtaining high-quality activated carbon is a significant critical path. Currently, activated carbon has a surface area of about 1,500 square meters per gram. That sounds very impressive, but improving energy density means achieving much higher ratios of surface area to mass. One interesting but highly speculative approach is to build supercapacitors with electrodes coated with carbon nanotubes that are fabricated and laid down to optimize the ability to trap electrolyte ions.

If this scheme could be made to work, it might well represent a revolution in energy-storage technology. However, research is still focusing on basic technologies and hasn't even advanced to a proof-of-concept prototype yet. Even if it can be shown to work, cost-effectively producing such supercapacitors will be a challenge. In the meantime, supercapacitor makers like NessCorp are trying to refine and cost-reduce their existing product and find new applications niches to keep them afloat.

BACK_TO_TOP* RESURGENT CALDERAS (3): Evidence indicates that the catastrophic eruptions that form resurgent caldera are surprisingly short lived. Studies of sea-floor cores with ash layers associated with the eruption that created the 28 kilometer (17.4 mile) wide Atitlan caldera in Guatemala 84,000 years ago -- which spewed out 300 cubic kilometers (70 cubic miles) of ash -- only lasted 20 to 27 days. Apparently a plinian column rose and fell a number of times in that interval. Evidence also indicates that the eruption that created the huge Toba caldera spewed out more than 1,000 cubic kilometers (240 cubic miles) of ash in as little as 9 days.

After the eruption, typically a lake fills the new caldera; sediment erodes the caldera wall and accumulates at the bottom of the lake. Then the caldera floor begins its slow resurgence -- though the resurgence doesn't normally occur in the center of the caldera, and its motion is usually skewed from the vertical. In some cases, including Yellowstone, two separate centers of resurgence are present in one caldera.

It was the recognition that young lake sediments had been raised hundreds of meters that allowed van Bemmelen to show that the resurgence of the floor of the Toba caldera had formed the 640 square kilometer (250 square mile) island of Samosir. Since the Toba caldera is only about 75,000 years old, the resurgence may not yet be complete. At Cerro Galan, resurgence of more than one kilometer (0.6 mile) has raised the center of the caldera to an altitude of more than 6 kilometers (3.75 miles) above sea level, making it one of the highest mountains in Argentina.

After resurgence come the final stages in the evolution of a caldera: the relatively quiet effusion of dacitic or rhyolitic lava from a necklace of vents along the ring fracture. Typically, the volume of material released is small, but the effusions continue intermittently long after the catastrophic caldera-forming eruption. At Long Valley, distinct episodes of effusion took place 500,000, 300,000 and 100,000 years ago.

The volcanic events associated with the formation of a caldera may continue with little violence for up to a million years. Hot springs and geysers, the result of geothermally heated water that finds its way to the surface, may be present for much longer than that.

* A caldera-forming eruption would be cataclysmic. Consider a 1,000 cubic kilometer (240 cubic mile) eruption. A tract of land with a surface area of possibly 500 square kilometers (195 square miles) would sink, and the resulting caldera would be filled entirely by ignimbrite. A surrounding area of up to 30,000 square kilometers (11,575 square miles) would also be covered by ignimbrite; the depth of the cover would range from more than 100 meters (330 feet) on the caldera rim to a few meters at the farthest extent of the ignimbrite. Destruction within this area would be complete.

Fine co-ignimbrite ashes would be dispersed over a major portion of the Earth's surface. This would interfere with ground and air traffic over the short run, and the disruption of at least a year's crop over the dispersal area. The ash would also modify the Earth's climate for a number of years.

A caldera-forming eruption might be predicted by the "leakage" of dacitic or rhyolitic magma to the surface as a ring fracture develops. Seismic signals might indicate the movement of magma into a chamber a few kilometers below the surface. The site of the chamber would be confirmed by a local anomaly in the Earth's gravitational field, since the density of magma is less than the density of solid crustal rock. Another important indicator would be the rise of the terrain and, particularly, an increase in the rate of rise. This could be revealed by conventional surveying techniques. Such signals do not indicate any timetable for an eruption, but they should not be ignored.

Resurgent calderas have benefits; the geysers and hot water may persist for two or three million years after the eruption and could be a useful source of energy. Resurgent calderas also may deposit useful minerals; the Kari Kari caldera eruption left silver lodes, whose mining made the city of Potosi on the caldera's rim the largest city in the Western Hemisphere in the 17th century.

It is fortunate that eruptions that form resurgent calderas are rare. We are beneficiaries of the catastrophes of the past. We may not feel so fortunate if such eruptions take place in the future. [END OF SERIES]

START | PREV* THE BLIND WATCHMAKER (1): I've long tried to ignore the squabbling over modern evolutionary theory (MET), but the squabbling got loud enough to make me finally wonder: Do the criticisms have any basis in fact? That led me to a book, Richard Dawkins' THE BLIND WATCHMAKER, that I found stimulating enough to summarize here. It's roughly half on evolutionary biology and half on debunking creationism, which despite the fact that it was written in the mid-1980s is still much on the mark -- not surprising, since creationists always recycle the same old arguments.

* Dawkins introduces his work with a subtitle comment: "Why The Evidence Of Evolution Reveals A Universe Without Design". He takes as his starting point the book NATURAL THEOLOGY, an 1802 work by English theologian William Paley. The focus of Paley's book was to show that the elaborations of the forms and details of life on Earth implied the action of a higher power, a Designer. Dawkins gives Paley a respectful treatment: in 1802 his thinking was state-of-the-art, and his writing was clean and persuasive.

In 1859 Charles Darwin published THE ORIGIN OF THE SPECIES and overturned Paley's ideas. In Darwin's view, creatures weren't designed as such. Species were mutable, with individuals being born with small variations in traits. The traits of individuals that survived and propagated were passed on; the traits of those who died out without leaving progeny died out. According to Darwin, "natural selection" was enough to account for the entire diversity of nature. Later generations of researchers would elaborate on Darwin's ideas, but his work still remains at the core of MET.

Critics sometimes contrive arguments that MET is not scientific because it is "non-falsifiable", meaning that it is a simple assertion that cannot be proven wrong but has no evidence to back it up. However, much of what MET states is supported by plenty of evidence. The variety of dogs demonstrates the mutability of species and the way their forms can be modified by a process of selective breeding. They are all clearly human-made, or at least human-modified, forms: no pekinese could survive in the wild. Crop plants have in some cases gone through similar drastic modifications: it is startling to realize that a few thousand years ago, corn looked pretty much like an ordinary sort of grass. Now it features hugely distorted heads with heavy stalks to support them. It can no longer disperse seeds on its own and would die out in a year or two if humans didn't take care of it.

Species are so mutable that zoo-keepers trying to preserve rare animals find it difficult to maintain captives that really match their wild cousins. Animals that are happy with being captives tend to breed much more easily than those that aren't, and so zoo animals tend to become increasingly tame from one generation to the next -- which still doesn't mean that it's a good idea to walk into a tiger cage. A Russian silver fox farm made an effort to breed more docile foxes, and within twenty years came up with animals that clearly seemed more like dogs than foxes in their appearance and behavior.

Of course, these are examples of artificial selection, but natural selection can be demonstrated easily enough. Take a culture of harmless bacteria, and then douse it with a toxin that kills the culture off 100% -- no survivors. Repeat this action as many times as desired and get the same results. Now take ten cultures of the same bacteria and administer the toxin in graded doses, from a very small dose to the maximum dose. Take the culture that was given the biggest dose for which some of the bacteria survived, then use these survivors to create ten more cultures, which are given the same treatment. Keep repeating this procedure, and eventually the result will be cultures of bacteria that shrug off the maximum dose of the toxin.

This is a lab experiment, but much the same can be seen in nature. The most notorious example is the emergence of "antibiotic-resistant bacteria". The introduction of antibiotic drugs in the middle of the 20th century provided medicine with a powerful set of weapons against dangerous bacterial infections, but even at the time the inventors of antibiotics knew that bacteria would evolve to defeat the antibiotics as they were, and now we are suffering from an ever-rising tide of bacteria that shrug off drugs that would have killed them off neatly thirty years ago.

Ironically, one possible solution for this problem is an exercise in biological selection as well. The Soviet Union long bred strains of "bacteriophages" -- viruses that infect and kill bacteria -- to deal with bacterial infections, with new strains of bacteria dealt with by selective breeding of new strains of bacteriophages. The modern Russian state still uses the approach and has been trying to export it.

As far as more complicated organisms go, metal electric power towers that are clad in zinc to resist corrosion will form zinc deposits that kill normal grasses and other plants. In fact, most such plants grow perfectly well around the towers -- but on examination they are strains that can tolerate high levels of zinc. Try to bring in plants that grew up far away from a tower, and they will die. [TO BE CONTINUED]

NEXT* NO BANANAS? According to an ECONOMIST article ("Going Bananas", 22 October 2005), bananas are the fourth largest food crop in the world, after wheat, rice, and maize. Bananas are a staple of the diet of about 400 million people, and are commonly raised on small farms in the tropics. In the US, bananas are a sweet, put on breakfast cereal, but they mean survival in many areas of the world, with the starchy plantain banana in particular acting as an analogue to the potato.

Another interesting fact about bananas is how they grow. All banana strains in existence today are derived from two strains, Musa acuminata, originally from what is now Malaysia, and Musa balbiana, from what is now India. Bananas don't grow on trees, the plant instead being a very structurally robust herbal, with a "pseudostem" erupting from the ground in a whorl of fronds that, eventually, end up as bunches of bananas. The acuminata banana is only about the size of an okra pod or a sweet pickle, with the fruit carrying peppercorn-sized seeds; the balbiana banana is about four times bigger and the fruit is crammed with seeds. The plantain is a hybrid of the two types.

Somewhere along the line, a farming culture found a mutant line of bananas that had vestigial seeds and decided to cultivate it. The lack of seeds in domesticated bananas is a very important fact, because it means that banana plants have to propagated by replanting cuttings taken from the base of a parent plant. That means that the genetic diversity of bananas is not very great, and so the global banana crop is highly vulnerable to diseases.

In the 1950s, nearly all bananas grown commercially were of a single strain, the Gros Michel, which was said to have been unusually tasty. It was all but wiped out by a fungus named "fusarium" that came from Panama. The Gros Michel now only survives in remote areas of Uganda and Jamaica. The current commercial banana strain is the Cavendish -- about the only type of banana sold in the West out of the wide range of strains, a bizarre situation compared to, say, apples -- but it is now threatened: a mutant strain of fusarium arose in 1992 and wiped out banana plantations in Malaysia. The disease remains local to Asia for now, but nobody expects this state of affairs to last much longer. Other strains of bananas grown as staples in Africa and Asia are also presented with serious fungal and other threats.

Banana research is dominated by the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium. Although Belgium might seem to be a strange place to be growing bananas, the university has cultivated 1,175 different strains, learning how to cryogenically freeze samples so they can be preserved. The location has advantages for banana research: since bananas are not grown there, the specimens can neither pass diseases nor pests to local crops, nor pick them up in turn.

Hybridization of domesticated banana strains is difficult, since they have little ability to reproduce sexually -- but they can do so with a lot of help in the form of researchers accumulating pollen from male plants to inseminate female plants, and then sorting through the fruit that results for seeds. A tonne of such bananas will produce a handful of seeds, only about half of which will germinate. Researchers there are also working on transferring genes between strains to improve disease resistance, and a disease-resistant strain is now being field-tested in Africa. There is a certain irony in that humans, having decided to preserve a plant line that would have died out on its own, are now forced to directly intervene in its evolution so that it does not die out in the future.

BACK_TO_TOP* BATTLE OF PALMDALE: America during the height of the Cold War was a different place than it is now, with one of the particular features being the fact that the authorities could get away with a lot more. A case in point was the day when the US Air Force bombarded a southern California town.

During the 1950s, interceptor aircraft often used salvos of unguided rockets to shoot down intruders. At least, that was the plan; the idea wasn't all that practical, though during the Vietnam War there was a case or two in which US aircraft shot down North Vietnamese MiG fighters with unguided rockets. These incidents were pure freaks of chance: strike aircraft carrying unguided rockets for ground attack loosed them at a MiG to scare it off, and managed to score a hit.

The standard US unguided rocket, then and now, was the 70-millimeter (2.75-inch) diameter "Folding Fin Air Rocket (FFAR)", which was carried in pods, with the rockets popping out spring-loaded tailfins after launch. The rockets jinked all over until they stabilized, which wasn't too much of a problem for blasting a spread of rockets at a truck convoy or the like on the ground, but seemed unlikely to score a hit on an aircraft unless it was a big one. The usual comment of those familiar with supposed use of unguided rockets in interceptions was: "It was a wonder they could hit anything with them."

The Germans had used unguided rockets successfully during World War II to break up American bomber formations, but the target in that case was a large number of bombers flying in a small chunk of sky, huddled up for the mutual protection of their defensive guns. In the nuclear age of the 1950s, a single bomber could destroy an entire city, and the nice fat target of a big bomber formation was history.

However, there was a reason for going with unguided rockets in the 1950s: collision-course intercepts. Traditionally, to shoot down a bomber, an interceptor got on its tail and blew the intruder out of the sky with automatic cannon, but with the development of modern radar and electronics, it was possible to vector an interceptor on a "collision course" against an intruder from the front or side. The problem was that the two aircraft flashed past each other at high relative speed -- so quickly that bomber crews on the receiving end of practice intercepts might not even see the interceptor coming and going -- meaning that there was very little time to score hits with automatic cannon. The only way to do that at the time was to loose a salvo of unguided rockets at the target; one hit by a rocket, with its relatively big warhead, would be lethal. There was also the problem that combat aircraft could often soak up many cannon hits, and so using rockets even for traditional tail-chase intercepts made a certain amount of sense. The real solution was the guided air-to-air missile (AAM), but such weapons were only under development at the time. They wouldn't come into widespread service until the 1960s, and wouldn't become really effective until well into the 1970s.

In any case, in the 1950s there were several interceptor aircraft that were armed only with unguided rockets -- no cannon. I had heard a vague story that two such interceptors had tried to shoot down a target drone that had lost radio control -- "slipped the leash" -- and failed to destroy it despite using up all their rockets. I finally got all the details from an article in AIR & SPACE magazine ("Fast, Cheap, & Out Of Control" by Peter W. Merlin, August-September 2005). The story turned out to be interesting, and it's no surprise it was obscure: the military would have preferred to forget about it.

* On 16 August 1956, a Grumman F6F-5K Hellcat target drone was sent aloft from the Point Mugu Naval Air Station, in southern California up the Pacific coast from Los Angeles. The Hellcat had been one of the great US Navy fighters of the Second World War, but now it was reduced to the status of a target, painted red and flying under radio control.

Or at least it was supposed to be flying under radio control. Although the target area was over the Pacific, the Hellcat decided to head towards Los Angeles instead. Nobody wanted the unpiloted aircraft to crash into a school or whatever, so two US Air Force Northrop F-89D Scorpion interceptors were scrambled from Oxnard Air Force Base, not far from Point Mugu, to destroy the wandering drone. The Scorpion was a subsonic jet aircraft, with a two-man crew and a sophisticated (by the standards of the time) all-weather radar fire control system, armed with a pod of 52 FFARs on each wingtip. The two F-89Ds carried a total of 208 rockets in all.

The Hellcat actually passed over Los Angeles; of course, shooting it down over the city would have been lunacy, and the interceptor crews could only hold their breath and wait for the drone to get clear. It finally decided to orbit over the town of Santa Paula, where the interceptor crews tried to get opportunities to take a shot at it. They were using an automatic fire-control mode, but as was not unusual for high tech avionics in those days, the fire-control system malfunctioned, and they didn't get a single rocket off.

Then the Hellcat decided to meander for a time, eventually turning back towards Los Angeles. The Scorpion crews switched to manual fire control and loosed salvos of rockets at the drone. They missed the Hellcat, the rockets falling to the ground to start a raging brush fire. They tried again, with no better luck, starting two more brush fires, one of them fueled by oil rigs in the unintended target area. Finally, as the drone headed toward Palmdale, the Scorpions fired their last rockets at it. They missed again.

This time, the rockets fell into Palmdale. A piece of shrapnel smashed through the living-room window of one house, passing through a wall to end up in a cupboard. Another fragment passed through a garage and home. A car's front end was shredded when a rocket fell in front of it. Astoundingly, nobody was hurt. Explosive ordnance disposal teams from Edwards Air Force Base picked up 13 dud rockets from around Palmdale. It took hundreds of firefighters two days to put out the three brush fires, after the blazes had consumed hundreds of acres.

The Hellcat finally wandered over the Mojave Desert near Palmdale, where it ran out of fuel, falling to earth in an uninhabited area but cutting three power lines doing it. By the records, the incident seems to have attracted very little public attention. Later models of the F-89 carried Falcon guided AAMs and were likely more effective. They could also carry the Genie missile, which was unguided but carried a small nuclear warhead -- leading to the passing thought that Palmdale might have got off lucky.

The author found fragments of the aircraft in that area in 1997. He also cited the names of the aircrews of the Scorpions in the article; I was reluctant myself to pass them on, but I do have to mention that the last name of one of them was "Einstein".

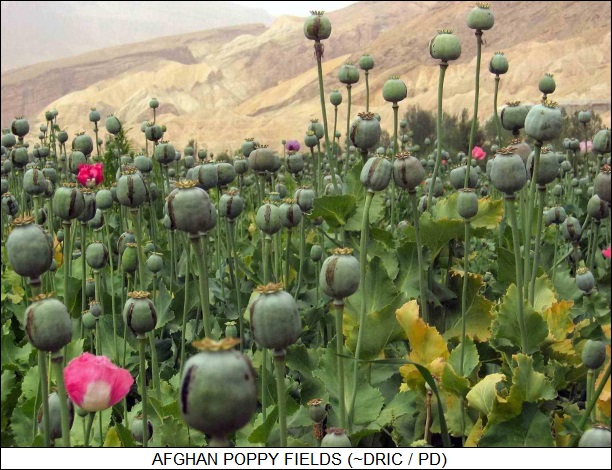

BACK_TO_TOP* POPPY FIELDS: An article in THE ECONOMIST ("Not What The Doctor Ordered", 8 October 2005) points out that the international effort to destroy Afghanistan's opium poppy agriculture is trapped in an ugly dilemma: the majority of Afghan farmers don't have any other cash crop to raise, and it will take a long time to fundamentally change the system.

The French-based Senlis Council suggests an alternative: legalize growing opium poppies. This is not as backwards as it sounds, since opium poppies are legally grown in Australia, India, Turkey, and France for production of legitimate pharmaceutical opiates. Given that medicines are in short supply in poor countries, large-volume opium production from Afghanistan might be what the doctor ordered.

The problem is that, in countries where opium poppies are grown legally, the business is under very tight control. Nothing in Afghanistan is under much control at all. Since illegal drugs in general fetch a higher price than legal ones, the temptation to divert opium production to the black market would be very high. Senlis acknowledges this, but claims that legalization would be the best of all the bad alternatives. Westerners involved in opium eradication in Afghanistan fear that the idea will muddy the waters and are giving it short shrift.

* VIRTUAL MACHINES: An ECONOMIST article ("A New Way To Stop Digital Decay", 17 September 2005) reports on efforts to preserve data stored on digital media. It might seem like data stored on a plastic CD-ROM is much more permanent than that printed on paper, but technological progress means that in ten or twenty years, the technology to read that CD-ROM may be long obsolete and hard to come by. In 1986, for example, the BBC built a multimedia database for Britain and distributed it on laserdiscs that could be read by a BBC Micro home computer. This was essentially a proprietary system, and all the material was nearly lost; somebody spent over two years using a creaky old BBC Micro to port the database to a PC format.

The only way around this problem is to make sure that archival materials are updated to current media on a regular basis. However, even if that's done, there's another problem: file formats. For example, the popular GIF image file format is now being replaced by the more capable PNG format, and so in a decade or two or three, it may be hard to find anything that can read the GIF format.

The National Library of the Netherlands has a solution: file decoders written for a "virtual machine", essentially a computer implemented in software that runs on top of real computer hardware. The idea is not new; old videogames are often run on PCs without any changes to the game software, simply by implementing software that operates like the game machines that originally ran the games. If a new type of computer is introduced, all that has to be done to run the file decoders is to port the virtual machine to the computer.

The implementation is actually being performed by IBM. Work is now being done on decoders for GIF and JPEG image files, with a decoder for Adobe PDF document files next on the queue. IBM is also talking with pharmaceutical companies to develop decoders for data files storing results of clinical trials.

BACK_TO_TOP* RESURGENT CALDERAS (2): It might seem the most likely place for an eruption that forms a resurgent caldera would be a subduction zone, the boundary on the surface of the Earth where a plate of oceanic crust slides under a continental plate and plunges into the underlying mantle. Subduction zones are normally sites of intense seismic and volcanic activity; the Toba caldera in Sumatra is near a subduction zone. However, it's not always that simple. Most of the younger calderas in the US, for example, are hundreds of kilometers from any modern subduction zone.

Still, resurgent calderas are not randomly distributed around the globe. The ignimbrites that characterize them result from the eruption of dacitic or rhyolitic magma, which is viscous, rich in silica, and typically produced where the continental crust is thick. As a result, resurgent calderas may form in regions of the continental crust where a thermal plume (a "hot spot") in the mantle of the Earth is large enough and long-lasting enough to melt huge volumes of rock. The plume does not melt the continental crust directly; instead, it melts part of the mantle to create a basaltic magma. The basaltic magma rises, melting the rock at shallower levels.

In the US, the Yellowstone caldera lies at the northeastern end of a trail of volcanic activity that begins in Idaho in the basaltic rock of the Snake River plain. Over the past 15 million years, the focus of volcanic activity has shifted along the trail to its present position in Wyoming, possibly in response to the movement of the plate that includes the North American continental crust over a stationary thermal plume in the mantle.

A number of other calderas, no more than a few tens of millions of years old, are found in a zone many hundreds of kilometers wide in Nevada, Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico. The youngest caldera in the group is on the flanks of the Rio Grande Rift, which runs for hundreds of kilometers northward through New Mexico into Colorado. It is thought the continental crust at the Rio Grande Rift has somehow been thinned, producing the rift itself. A similar process is thought to have caused rifts in the oceanic crust near many of the island arcs in the Pacific.

In Argentina and Bolivia, resurgent calderas have formed not only along the main volcanic cordillera of the Andes, but also in a second cordillera more than 200 kilometers farther inland. Here there is no evidence of crustal thinning; on the contrary, the continental crust may be as much as 40 to 50 kilometers (25 to 30 miles) thick under the Cerro Galan and Kari Kari calderas. It is thought magma conduits to the surface of the inland cordillera may have developed by fracturing of the crust caused by the pressure of moving magma.

* Formation of a typical caldera follows a series of steps: precaldera forming, caldera collapse, eruption of air-fall material and pyroclastic flows, postcaldera resurgence, and finally late-stage extrusions of lava.

Precaldera doming is the rise of the Earth's surface that precedes a massive eruption. It happens when a great volume of magma intrudes itself into a shallow level of the continental crust, creating a "pluton", or magma chamber, whose top may lie only a few kilometers beneath the surface. The doming causes stress that leads to the next step, the collapse of the caldera -- it is thought either through upward pressure on the crust, or by subsidence of the crust into the magma.

The magma at the top of the pluton has a temperature of 700 to 1,000 degrees Celsius (1,200 to 1,700 degrees Fahrenheit) and is rich in dissolved gases, mostly water vapor. The magma rises toward the surface along the newly-opened ring fracture. As it rises, the pressure on it lessens, until at a depth of about a kilometer the gases come out of solution, much as they do when the cork on a bottle of champagne is popped. Dacitic or rhyolitic magma is much more viscous than champagne (or even basaltic magma), however, and so the gases do not merely bubble away. Instead, they blow the magma apart. The magma escaping from the pluton toward the surface expands into pumice and explosively fragments into incandescent solid particles ranging in size from micrometers to meters.

If the rate of the eruption is great and the vent is relatively small -- possibly 50 or 100 meters (165 or 330 feet) in diameter -- an eruption column develops, rising tens of kilometers into the atmosphere. The eruption column of Mount St. Helens reached about 20 kilometers (12 miles). The pumice in the column is not simply blasted upward from the vent like buckshot from a shotgun. Directly above the vent, the upward velocities are hundreds of meters per second. As the pumice rises, however, it rapidly decelerates; it is slowed not only by gravity but by aerodynamic drag. Then a second process begins to add energy: the decelerating mass of incandescent pumice, ash, and gas captures and heats up air from around the column.

As a result, the mass becomes buoyant and begins to rise convectively; it may even accelerate upward again. Such convective eruption columns are known as "plinian columns", after Pliny the Elder, whose description of Vesuvius in 79 AD is the first documented example. Convection can send a plinian column to as high as 50 kilometers (30 miles).

* Massive plinian columns may indicate the beginning of a catastrophic collapse that creates a caldera. As the eruption proceeds, however, the plinian columns typically give way to pyroclastic flows, which make up by far the greatest part of the volume of the eruption. The transition from plinian column to pyroclastic flows is caused by the increasing size of the vent as the eruption proceeds and loss of gas in the magma in the pluton, which robs the column of the heat needed to keep it going.

As the materials fall back to the ground, they surge forward rapidly. It is known from the distribution of the ignimbrites they deposit that they can sweep over hills as much as a kilometer high and travel distances of up to 150 kilometers (95 miles) at velocities of 100 meters per second (360 KPH / 225 MPH). The flow travels fast because it is in a partially fluidized condition, still loaded with hot gases and fine particles that act as a lubricant -- as well as the fact that the mass of the flow has fallen several kilometers from the sky, giving it considerable kinetic energy.

The remains of a pyroclastic flow is a blanket of pumice and smaller particles that can be several meters thick more than 50 kilometers (30 miles) from the vent. In addition, the fine particles trapped by the flow typically form a secondary ash cloud that rises many kilometers by convection. The subsequent fall of particles from the cloud can deposit a thin layer of ash over a region much larger that the one covered by the ignimbrite of the pyroclastic flow itself. In fact, the layer, which is called "co-ignimbrite" ash, can amount to as much as a third of the entire volume of the ignimbrite.

The eruptions that form resurgent calderas are always eruptions of dacitic or rhyolitic magma, not basaltic magma. Basaltic magma has lower viscosity, and gases coming out of it easily escape, preventing a catastrophic explosion. Basaltic magma also doesn't produce much in the way of fine ash; fine particles more easily lose heat than large ones because of the higher ratio of surface area to volume, and in the absence of such particles convective currents don't arise in the atmosphere. Basaltic magmas do not form plinian columns.

The "fire fountains" seen on the active volcanoes of the Hawaiian Islands provide an excellent example. In a fire fountain, great volumes of lava are sprayed high into the air, but the lava, which is basaltic, emerges as large liquid gobbets, sometimes a meter or more across, and is simply spattered around the vent. [TO BE CONTINUED]

START | PREV | NEXT* LIQUID TREASURE (6): There are success stories in the water supply business, including Chile, South Africa, and Australia. Chile has achieved near-universal water supply, with an efficient operation run under contract to Suez. Everyone is charged for the full costs of their water, with poor people able to obtain a rebate.

South Africa has been another star. Under the apartheid regime, water utilities were focused on providing water to the white elite in the cities, while blacks in the countryside were neglected. When the African National Congress took power in 1994, about 14 million South Africans, a third of the population, lacked access to clean water. Now 9 million of those people have access, and the rest are expected to obtain access by 2008. "Access" in this case is defined as piped water in cities, or an outlet within 200 meters (650 feet) of every home in villages.

South Africa passed a comprehensive water bill in 1998 that cleaned the slate on the old water rights laws, made water allocations temporary and tradeable -- more on these concepts below -- and dictated that all users, except for the most poor, bear the actual costs of their water. Originally the poor were given an allocation of 25 liters (6.6 US gallons) of water a day at a minimal rate, but even that was more than the poor could bear, so now the poor get 25 liters a day free. Although the government is clearly in control, private contractors are welcome and encouraged.

The real superstar is Australia. Water is clearly a problem DownUnder, and originally the nation took something along the lines of the American route, building dams and providing water to farmers at subsidized rates. That has now all changed. Now the government claims ownership of all the water, with users granted access rights. A system of water trading was introduced, in which those with more water than they could use could transfer rights to it to others for a fee, discouraging waste and encouraging competition. In the cities, all water is metered, with users paying by volume instead of the wasteful flat rate. The system is designed to take into consideration all uses and costs of the water.

Laggards are starting to get wise as well. Even in California, at the very soul of tangled American water bureaucracy, people are taking a more realistic view of water use, and considering innovations such as water trading. More progress will require revising the laws that backed up the old system, but nobody thinks that will happen soon.

In India, where the government bureaucracy is at least as tangled but the resources are far more scarce, there are rays of light as well. A non-governmental organization (NGO) named "Tarun Barat Sangh", led by Rajendra Singh, is working with villages to build up their "rainwater harvesting" infrastructure, building up systems using old cisterns and other hydrotechnologies linked with new installations to allow them to suffer through droughts with less pain. The enthusiastic Singh, called the "Water Man" by the media, claims to have helped set up thousands of rainwater harvesting systems not only in villages but in cities. He's strongly skeptical of the central government's scheme to interlink all the country's rivers, not just because he sees it as overkill but because it's a bureaucratic plan in which the "little people" have little say. Rainwater harvesting might not be the answer to all of India's water problems -- but in devolving authority and ownership to villages, it sets a precedent for the future.

* In summary, modern water planning is based on three assumptions:

Green activists don't like water misuse or big water projects, but they are very reluctant to accept market mechanisms; that water should be universally metered; and that people should pay the actual costs of the water, including environmental costs. Such attitudes promote waste, and, as discussed, in places where water prices are kept unrealistically low, the poor are usually not the beneficiaries, with the system focusing on the big users and lacking the funds or the interest in providing services to the small fish. Even if full rates are charged, there are ways of ensuring that the poor will not be shut out, such as the Chilean use of rebates and the South African provision of a free daily minimum.

Market mechanisms also mean cleaning up legal tangles over rights and ownership, and setting up trading mechanisms. Private firms will play a vital role in any market-based water system, though as has been repeatedly emphasized in this survey, private firms will not own the water and they will remain under overall government oversight.

Technology of course has a role to play. Drip irrigation, popular in Israel, is much more efficient than spray or flood irrigation, but it not widely used in other desert lands yet. Big technologies such as dams still remain important, though they have to be handled carefully, and there is no sense in turning to an elaborate and expensive solution when a simpler and cheaper one will do the job. It is not clear if the Johannesburg goal of halving the number of people without access to water by 2015 will actually happen, but if it doesn't, it won't be for any lack of good ideas for making it happen. [END OF SERIES]

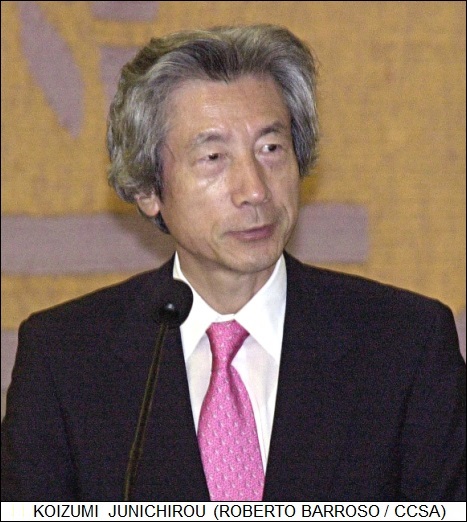

START | PREV* SUNRISE: A survey in THE ECONOMIST of contemporary Japan ("The Sun Also Rises" by Bill Emmott, 8 October 2005) used the recent elections in Japan as a springboard. Koizumi Junichirou, prime minister since 2001, had tried to push a bill privatizing the Japan Post service through the Japanese Diet (Parliament), and when it was rejected he took drastic action, dissolving the Diet and calling for new elections. In the election, he did all he could to block the reelection of members of his Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) who had voted against the Japan Post bill, putting his own candidates in their place. There were those who suspected this was an act of political "seppuku" -- ritual disembowelment -- but this September Koizumi pulled it off.

Privatizing the postal service might not sound like the stuff of political revolutions. In itself, it wasn't, but it was a landmark in a process of gradual social and political turnaround that seems likely to continue. Why this is so requires a bit of background.

During the boom years of the 1980s, Japan's industries were the object of global admiration, as well as jealousy and fear. Even when things were at their best, however, there was somewhat more appearance than substance to things. Where this was most true was in the belief that wise government policies had created this economic miracle. To be sure, the Japanese government did some things right, but success was more in spite of the political system than because of it. In truth, while Japan's industries were world-class, Japan's government was second-rate.

Politics were dominated by the LDP, creating an effective one-party state. Politics were almost completely cynical, based on the acquisition of power and influence, with factions in the LDP maneuvering with each other for control. When the economic bubble finally popped in the 1990s, the deficiencies of the government were laid bare -- too addicted to pork-barrel contracts; politicians whose ethics would get them into big trouble in most Western states; and a financial system that was rotten with bad loans, granted mindlessly during the boom times and resulting in a mountain of debt.

There was high unemployment, even poverty and homelessness. Suicides soared, not too surprising in a nation where suicide is wired in various ways into cultural traditions, but crime rose somewhat too. The Japanese, once regarded as frugal, now only save about 5% of their income. Still, the economic changes were not all bad, at least on the macroscale, though not necessarily all that comfortable to the people on the bottom of the economic pyramid. In the good times, Japanese industry had a tradition of paternalistic "lifetime employment", though this was something more of a custom than a hard and fast rule. Still, there was resistance to firing personnel even when they were excess. In the new regime, companies hired on large numbers of "furiba" -- from the German "frei arbeiter (part-time worker)" -- resulting in much greater labor flexibility.

With the economy now finally starting to pick up again, thanks in good part to exports to China, full-time employment is starting to pick up, but the industries have become used to the idea of a more flexible approach to labor, and aren't unhappy about the fact that Japanese labor is, these days, not all that expensive. There is a looming problem that the population is graying and the labor market will shrink, but Japanese companies have been pathfinders in the use of industrial robots, and current social circumstances are encouraging for further automation. The companies may not find keeping up with a declining labor market all that difficult, ensuring a high GDP per head.

In the meantime, the ghastly debt, kept afloat by the reluctance of the government and banks to pull the plug on "zombie" companies that couldn't make good their repayments, has started to fall drastically, to less than half the level of 2001. This reduction was mostly due to mergers that finally allowed the bad loans to be properly written off. The banks are feeling much healthier.

Changing times have also meant macroscale improvements and microscale discomforts for businesses. Although Japan is stereotyped as over-regulated, formally speaking the regulatory environment has traditionally been loose, governed mostly by traditions and obnoxiously vague laws that government bureaucracies could implement as they saw fit. Now corporate entities are being required to conform to more specific laws ensuring transparency and accountability, like they would in the West. To be sure, the new laws are a mixed lot, with some making life easier for company presidents, and enforcement is still weak, but things seem to be headed in the right direction.

The government itself is undergoing a comparable form of discipline. Koizumi's privatization of Japan Post is one of the centerpieces. Japan Post, it turns out, is no mere postal service, it also operates as the biggest personal-deposits banker and personal insurer in the country. This not only meant the government obstructed the operations of private companies in those fields, it also gave LDP politicians an immense source of "black budget" that could be siphoned off without accountability. Japan Post was indeed a distinctively Japanese institution.

The reform that Koizumi pushed through was also distinctively Japanese, since it will privatize Japan Post over ten years, in gradual stages; the Japanese do not like to do things abruptly. There was unusually large turnout for the special election, with voters clearly preferring the gradual approach to the more drastic prescriptions of the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), the LDP's main rival: the DPJ was crushed in the polls.

The privatization of Japan Post was, however, somewhat symbolic of changes, many of which had already been underway. The government had been cutting pork-barrel contracts, in particular working to get public works projects under control. Building projects had been a particular source of patronage, with the absurd result of seeming to pave the country over completely, ruining much of Japan's natural splendor of mountains, streams, and forests. Now there's an effort emerging to deal with the worst eyesores. Finally, new laws are imposing greater accountability and transparency on the government itself, while changes in the LDP are undermining the power of party factionalism.

Finally, there is the question of Japan's relationship with the outside world. The alliance with the US remains strong, surprisingly so with the differences in mindset and sometimes unhappy history between the two nations; it gives Japanese some confidence in their dealings with their rising trade rivals -- China, Taiwan, and South Korea -- and potential enemies -- meaning the unbalanced North Korean regime. North Korea has pushed Japan to measures that would have been unthinkable in the 1980s, such as launching spy satellites, built with American blessing and support.

Indeed, there is a touch of belligerence in Japanese leadership these days. Koizumi has caused controversy by going to the Yasukuni shrine, a memorial to the nation's war dead. Being a war memorial is not a bad thing in itself, of course, but Yasukuni also enshrines convicted war criminals as heroes, which is grating, and even claims that Japan's war was a crusade of national liberation of Asian nations from Western colonialism. This claim merely annoys Americans and other Westerners, but generates rage in China, Korea, and the Philippines, where the war is generally remembered in terms of Japanese barbarities. There are alternate options for remembering the war dead that are less controversial. Japan still remains basically pacifistic, and in fact has been gradually working towards the construction of regional economic and security alliances.

Koizumi plans to leave office for private life in September 2006. He is 63 and wants to have time to listen to music and go out to dinner. He is a political loner and will have little to keep him involved in politics once his time in office is done. The best-odds candidate for his successor is 51-year-old Chief Cabinet Secretary Abe Shinzou, a member of the politically prominent Abe clan and a strong supporter of Koizumi's reforms. Whether the momentum for reform accumulated under Koizumi will persist after he leaves office remains to be seen.

BACK_TO_TOP* NO BUBBLY: An essay in THE ECONOMIST ("Hold The Champagne", 8 October 2005) points out the generally quiet pleasure of Democrats in the Bush II administration's bad case of second-term blues: a troubled and unpopular intervention in Iraq, a flatfooted reaction to national disasters, high officials indicted for leaking the name of a secret CIA agent to the media. Bush now is starting to get flak from the Right -- the Left has always sniped at him, that's not news -- since conservatives who have been unhappy about the Bush II administration's lack of fiscal discipline and efforts to override the other branches of government are not as willing as they were to swallow their misgivings.

That gives Democrats some hope of believing the next president won't be a Republican. However, as the essayist pointed out, that's getting way ahead of things. The Democrats do not seem to be benefiting much from the problems of the Republicans. As House Speaker J. Dennis Hastert put it in a recent meeting of fellow GOP politicians: "I submit to you that even today, as tough as things seem, it is much better to be us than them."

The problem is that simply having an adversary in disarray is not enough: the Democratic Party needs to have good ideas, and such good ideas seem to be in short supply, with the party unable to resolve differences of opinion between moderates -- willing to meet conservatives in the middle -- and extremists -- who regard conservatives as agents of evil and are energetic in denouncing them in their blogs.

Bill Clinton had his unarguable, even well-documented, faults, but he was able to win the presidency, twice, by moving the Democrats towards the center. This important lesson is lost on the extreme Democrats, who regard concessions to moderation as a betrayal of basic principles. So far, no Democratic leader has emerged who seems acceptable to both factions, much less to the generally moderate independents who increasingly hold the balance of power in presidential elections -- and unless somebody emerges who is acceptable, the chances of the Democrats of winning the White House in 2008 don't make for a good bet. [ED: Twaddle, Obama won handily in 2008.]

BACK_TO_TOP* SMOLDERING EARTH: I had heard stories of underground coal fires that went on for years, but it wasn't until I read an article in SMITHSONIAN ("Fire Hole" by Kevin Krajick, May 2005), that I learned the fantastical details of the phenomenon.

Welcome to Centralia, Pennsylvania, in coal-mining country. Many decades of mining left the town and its surrounding area sitting over a lattice of unused mining tunnels, many of which had caved in. In May 1962, local sanitation workers began to burn trash over the entrance to an old mine just outside of town. Soon afterward, smoke began to seep up out of the ground as fire slowly crept its way through the coal seams.

At first, firefighters tried to dig trenches to cut off the fires, but the fires infiltrated beyond the trenches. Then they tried boring holes and pouring down wet sand, gravel, slurries of concrete, and fly ash, but traditionally "flushing" doesn't work, and it didn't in Centralia. State and Federal officials tried to dig another trench, a big one this time, and it didn't work either. Flooding was considered but rejected, because the area was too well drained. Digging a pit that would have had a good chance of isolating the entire fire area would have cost $660 million USD, more than all the property in Centralia was worth even if the ground hadn't been oozing up smoke.

The authorities gave up trying to put out the fire, and it is still burning. At last count, it covered 1.6 square kilometers (400 acres) and was spreading along four arms at 23 meters (75 feet) a year in each direction. It is believed that the fire will burn itself out after covering about 9.25 more square kilometers (3,700 acres) -- which could take over two centuries.

At first, the residents found the situation more strange than frightening; they could harvest tomatoes for Christmas in their heated gardens. Then people began to pass out in their homes from carbon monoxide poisoning. Sections of road began to subside into the ground as the coal beneath turned to ash, and in 1981 the ground opened up and swallowed a 12-year-old boy, who managed to save himself by grabbing onto a tree root. The Federal government finally bought out most of the 1,100 inhabitants of the town -- it was much cheaper than trying to stop the fire -- and leveled their residences with bulldozers. About 600 buildings were destroyed.

About a dozen die-hards, mostly old folks with no place else they want to go, cling on. The government doesn't want to evict them, though they could be poisoned in their homes, or even swallowed up into the ground along with their residences. Wild turkeys, deer, rabbits, and even the occasional bear walk down the streets where there were once houses; tourists drop in on occasion to see the little town out of the Twilight Zone.

There are dozens of other underground coal fires in the coal mining regions of the US. Pennsylvania has 38, the largest number for any one state; one's been burning since 1915. China has the most of any one country; one that had been burning for a century was just put out in 2003 after four years of effort. The coal fires amount to a substantial source of air pollution and a waste of an otherwise valuable resource, but in so many cases trying to extinguish the blazes has proven so difficult that people adopt the same solution as was applied to Centralia: let it burn.

BACK_TO_TOP* RESURGENT CALDERAS (1): As discussed in an article from some years back in SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN ( "Giant Volcanic Calderas" by Peter Francis, June 1983), the eruption of Mount St. Helens in southern Washington on 18 May 1980 ejected 0.6 cubic kilometers (0.14 cubic miles) of magma and volcanic ash, and left a crater two kilometers (1.25 miles) in diameter. It was regarded as an awesome event.

However, some 600,000 years ago, a volcanic eruption occurred 950 kilometers (590 miles) to the east, ejecting 1,000 cubic kilometers (240 cubic miles) of pumice and ash and leaving an elongated caldera (the name for a large volcanic crater) 70 kilometers (43 miles) across its longest dimension. The growth of vegetation and effects of glaciation have hidden the main features of that eruption; the most obvious remnant is the Old Faithful geyser in Yellowstone National Park. Yellowstone is a product of one of the largest-scale volcanic processes: it is a resurgent caldera, a caldera whose floor has slowly domed upward in the millennia since the eruption. Volcanic eruptions such as the one that formed the Yellowstone caldera are one of the greatest natural catastrophes, possibly equivalent to the impact of an asteroid.

Fortunately, they're rare. None have taken place through the few thousand years of recorded history, and in the US only three are known to have happened in the last million years. In addition to the one in Yellowstone, an eruption 700,000 years ago formed the Long Valley caldera in California, and an eruption a million years ago formed the Valles caldera in New Mexico.

Calderas of similar age may eventually be uncovered in other parts of the world. Still, it will probably turn out that in the past million years, no more than 10 eruptions of calderas have occurred world-wide. However, studies of the San Juan mountains in Colorado have revealed at least 18 calderas between 20 and 30 million years old, and many others of similar age have been recognized in southern New Mexico, Arizona, and Nevada. In the past decades, vulcanologists have made rapid progress in understanding the origins of giant, resurgent calderas and the catastrophic eruptions that form them.

* The fundamental mechanism of caldera formation was outlined early in the 20th century. The sudden ejection of large volumes of magma from a magma chamber a few kilometers below the surface of the Earth abruptly removes the support of the roof of the chamber, and the roof collapses, leaving a caldera at the surface. Calderas can range in diameter from a few kilometers to 50 kilometers (30 miles) or more.