* 22 entries including: Dawkins' THE BLIND WATCHMAKER, smart sensor networks, a history of barbed wire, Arabs less keen on terrorism, Iraq elections, possible exaggerations of flu scare, robot surgery, oceanic oil rigs & nodding donkey pumps, clean coal power, a colder Europe, shifting magnetic poles, adjusting years by seconds, terrorism as a business, Iraq exit, superfreighters, Detroit seeks fuel-efficient cars, Brazil's EMBRAER, airliner defensive systems, UN relief needs money, businesslike NGOs, estimates of oil peak.

* THE BLIND WATCHMAKER (11): Continuing our diversion through Paul Davies' THE FIFTH MIRACLE, we move back to a coarser view of the origins of life. The Earth seems to be about 4.5 billion years old, with the earliest traces of life being about 3.5 billion years old and our oxygen atmosphere about two billion years old -- though it wouldn't resemble the modern atmosphere for about another half-billion years.

The first billion years of the Earth's existence, as suggested by the cratered surface of our Moon, were characterized by asteroid and comet impacts -- sometimes really big impacts, powerful enough to boil off the oceans, with things not returning to normal for a millennium. The odd thing is that once this "hard rain" slackened off, ending its periodic sterilizations of the surface of the planet, life arose within a few hundred million years. As mentioned, some of the optimists believe that this suggests the inevitability of the rise of life, but there is an interesting alternate point of view that suggests life began well before the end of the hard rain era.

The hint comes from microorganisms known as "extremophiles". One of the first to be known was the bacterium Thiobacillus thiooxidans, which likes to live in solutions so acidic that they will dissolve metals, and certainly will kill off any competitors. Other extremophiles have been found that liked very salty, or alkaline, or hot environments. It is the heat-loving extremophiles or "thermophiles" that are of interest here. Some are capable of thriving in environments at temperatures of a hundred degrees Celsius or more, hot enough to boil water. Ideas that such thermophiles might be able to live deep underground go back to the 1920s, but it wasn't until the 1980s that live samples were obtained from drill cores. There was considerable skepticism at first, the critics claiming the bacteria were contaminants that originated in the surface world, but the evidence piled up and the critics had to admit defeat. Deep-underground thermophiles have been cultured in pressure cookers, something no surface world contaminant is likely to find a benign environment. It is now generally believed that such thermophiles form a layer into the surface of the Earth at least half a kilometer deep, and possibly well deeper.

The interesting idea is: maybe life began underground. The heat there would provide all the energy needed, all the required elements would be available as well, and even the most massive impacts would not disturb the underground world much. The concept was first put forth by Jack Corliss of the University of Maryland in 1981, to be promoted further by a paper written by astrophysicist Tommy Gold in 1992. The idea was not greeted enthusiastically at first, but it is gaining converts. One interesting fact in its favor is that some deep-underground bacteria have unusual, seemingly archaic, features in their metabolic cycles, as if they were precursors to surface bacteria. [TO BE CONTINUED]

START | PREV | NEXT* Anybody who doesn't follow military affairs might be surprised to find how environmentally conscious the US armed services are, but the Pentagon has been trying to adopt a "greener" image for some time, and not just for camouflage. According to THE ECONOMIST, the military did have to be dragged into their new mindset, by being slapped with massive costs for toxic cleanups on military reservations. However, the report card for the brass does include being responsive to public interests, and now the environment is part of the game plan for the services.

The US Army is building energy-efficient buildings, modifying their lawn irrigation systems to use less water, and recycling solvents. The US Air Force is a major user of renewable energy, with two of their bases largely powered by wind turbines -- a useful side benefit of the fact that military bases are often sited in desolate and wind-swept places. This exercise not only demonstrates the responsiveness of the services to the public will, but it often turns out to be cost-effective as well.

Some green activists have been skeptical, but the US Environmental Protection Agency has judged that the US Army's Fort Lewis, in the thoroughly green northwest state of Washington, is clean enough to no longer require any extraordinary level of monitoring. The Pentagon has specific, long-range environmental plans and seems determined to achieve their goals. There has even been direct cooperation with environmental groups: the military has collaborated with the Nature Conservancy to buy up lands, which can be used for the occasional wargame but otherwise set aside as natural habitat.

* According to a NEWSWEEK article, a group of MIT engineers named "Design That Matters" working on "appropriate technologies" for the undeveloped world has come up with an interesting idea: an educational slide projector called the "Kinkajou", named after a South American relative of the raccoon that has excellent night vision.

In undeveloped countries, books may be expensive and facilities may be primitive. The solar-powered Kinkajou can project slides from a spool with up to 10,000 entries onto any flat surface. The Kinkajou design was based on that of a Fisher-Price projector for small children, which had to be cheap, as well as durable to put up with the kind of abuse that toddlers can dish out. The Kinkajou uses plastic parts, including lenses, and costs about $50 USD in quantity; a slide spool costs about $12 USD. Aid agencies and nongovernmental organizations are very interested in the Kinkajou and see thousands of them in use within a few years.

* One of the interesting recent developments of the digital audio revolution is the rise of "podcasting", in which spoken-word audio presentations are downloaded from the Internet for "consumption" in a Mac iPod or other audio player. According to a NEWSWEEK article ("Professor In Your Pocket" by Peg Tyre, 28 November 2005), podcasting is starting to arrive on campus. Students who miss lectures can download them later and catch up with what's going on.

Critics suggest that podcasting courses undermines the interaction between instructor and student, and parents shelling out tuition wonder if this is what they are paying money for. However, for freshman 101-series courses, where the course material is not that demanding and the lectures are usually to packed halls, it's hard to see that podcasting makes much of a difference, except to students who find it much more convenient.

In the face of podcasting, some profs are becoming more like disk jockeys, preparing multimedia presentations with musical intros, sound effects, and citations from other profs or from primary sources. A few are even trying to drop the formal lecture session completely, simply telling their students to listen to the lecture on their iPods, with the class reserved for group discussion.

BACK_TO_TOP* SECOND THOUGHTS: The terrorist bombings on 9 November 2005 of American-owned hotels in Amman, Jordan, killed 60 people and wounded many others. According to an article in THE ECONOMIST ("Unfamiliar Questions In The Arab Air", 26 November 2005), the fact that the dead and maimed were all innocent bystanders -- most significantly, a wedding party of Palestinians -- has unsurprisingly done much to dampen public enthusiasm for holy war or "jihad" among the public in Arab lands. The mastermind of the attack, Jordanian Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, once a folk hero to Jordanians for his resistance to the US occupation of Iraq, is now all but universally despised in Jordan, even loudly disowned by his clan.

Few Arabs were too upset at jihadi attacks on Americans. Americans are not popular in the lands of Islam, and their popularity is not likely to increase all that much in any hurry even when -- there is no question of "if", it's just a question of "when" -- US troops get out of Iraq. Jihadi attacks that killed Shiite Iraqis also did not do too much to upset many Sunni Muslims; the Americans are a recent invention, the feud between Sunni and Shiite has been going on for 1,300 years. Now jihadi terrorism is getting too close to home. It was all very well to enjoy watching one's enemies torn by wild dogs, but it was foolish to think that wild dogs are particularly discriminating in who they attack.

Jordan was not the first Arab nation to feel the bite. The kidnapping and occasional execution of diplomats from Morocco, Algeria, and Egypt in Iraq provoked mass outrage in those countries. The Saudis have been fighting jihadis at home for about two years now; Saudi security officials claim that most of the progress against the terrorists is due to public disillusionment with acts of mindless and indiscriminate violence.

Westerners may take some satisfaction in this, but there is a dark side to the shift in position as well. Arab nations have traditionally tried to hush up terrorist actions on their soil, since such attacks suggest that local governments are neither universally popular nor completely in control, and the violence also scares off tourists. Now terrorist atrocities are played up, in order to justify the heavy-handed actions of "mukhabarats (state security services)".

Still, the increasing revulsion of the Arab public for acts of terror is real and sincere. Arab editors who are quick to criticize Western imperialism, both real and imagined, are now also condemning the jihadis for their excesses. Muslim preachers who once called for battle are now asking for restraint. Saudi TV -- broadcast through the Arab world by the Saudi-controlled ArabSat network -- has run series about jihadis and their victims. Some of the works have been cartoonish and propagandistic, but others have been well-written, showing the jihadis as misguided souls whose choices have turned out to be the wrong ones.

With support for jihadis drying up Arab governments, previously unwilling to work to help America out of its jam in Iraq lest they seem like stooges, are now more interested in fixing things. The awareness that an Iraq turned into a nest of jihadis means more attacks elsewhere has also been an incentive to provide help. Egypt and Saudi Arabia have been working on diplomatic efforts to bring Iraq's squabbling factions to the bargaining table.

Iraq remains the center of jihadi activity, and there seems no prospect of an end to bombings and killings any time soon. Still, there are signs of hope: many Sunni and Shiite Iraqis are sick of the bloodshed, and the Sunnis are beginning to see over the long term that attacks on Shiites may be unconstructive. The Americans will go, but Iran is right next door, and the refusal of Sunnis to make a deal may end up leaving them with an iron-fisted Iraqi Shiite government backed up heavily by Iran. Such a prospect makes at least a degree of discussion with the Shiites and even the Americans seem more acceptable.

A Saudi editor has suggested that Islam has been pulled between two poles -- one absolutist and emotional, the other pragmatic and realistic. He concluded that while the realistic approach may not win you everything you want, the absolutist approach risks losing all that you have.

George Orwell once made an observation that pacifists don't like seeing boys playing with toy soldiers, but couldn't think of an acceptable substitute: toy pacifists just wouldn't do. His conclusion from this was that humans have a certain innate enthusiasm for war, not always merely wanting good schools and roads and, in general, common sense, but at least on occasion flag-waving and victory parades as well. The corollary, of course, is that wars are by nature unpredictably destructive, and after performing a costs-benefits analysis and trying to fix the damage, common sense begins to seem more appealing after all.

* The Iraqi elections this month were another hopeful sign that there may be an end, someday, to the chaos there. Out of 15 million eligible voters, at least 10 million voted -- including many Sunni Iraqis, even in Sunni strongholds such as Fallujah and Ramadi -- and observers concluded the election process was "generally" satisfactory. However, al-Qaeda in Iraq denounced the election and promised attacks. The ground rules for the election included:

Despite the threats, election day was more or less peaceful, by the simple process of shutting down all ground and air traffic for two days. 150,000 Iraqi troops and police were deployed to keep order; foreign forces stayed in the background.

* In semi-related news, the Bush II Administration finally gave up their resistance to Congressional insistence on a blanket torture ban. Pressure for the move was so nearly unanimous that it is a bit surprising that the administration didn't give in before. President Bush and Senator John McCain, the prime mover behind the bill, shook hands before the cameras, though Senator McCain came across as unenthusiastic about the exercise.

The Bush II administration is now clearly in retreat on the demand for extraordinary rights to prosecute the war on terror. The US Senate promptly followed Bush's concession by refusing to extend the Patriot Act, the package of powers handed to the president after the 9-11 attacks. There are a number of other issues that will likely come to the surface very quickly, such as the status of prisoners being held indefinitely without charge or trial, the prison at Guantanamo Bay in Cuba, and Red Cross access to prisoners. It would seem unlikely that refusing to go the rest of the way and restore conventional concepts of justice would damage the administration's credibility beyond all repair. It is difficult to believe they would do so.

The matter of the alleged secret CIA flights around Europe remains open, if increasingly muddied. US Secretary of State Condi Rice -- who one suspects of having been an internal prime mover behind the change in administration policy -- made loud and clear public declarations that the US is going to act within the law, and also gave assurances behind closed doors to EU ministers that they generally pronounced satisfactory. The EU has a split mind on the matter, with one faction claiming the allegations are "credible" and another insisting that the denials made by the various states said to be involved should not be challenged without evidence. If really damaging facts come to the surface, the issue is likely to explode; if not, it will simply bore itself to death.

Finally, Bush has also conceded the apparent facts that the occupation of Iraq has been more troublesome than expected, and that the intelligence that led to the intervention was faulty. He does continue to insist that the intervention was justified. The administration has sensibly pulled back their lines to provide a more defensible position, but the momentum of the political battle is for the moment against them -- under fire, the president has just admitted that he authorized wiretaps of American citizens following 9-11, though he insists he was within his rights to do so -- and it will take more effort to restore the balance.

BACK_TO_TOP* FAKE FLU SCARE? As reported by an article in AAAS SCIENCE ("Pandemic Skeptics Warn Against Crying Wolf" by Dennis Normile, 18 November 2005), much fuss has been raised over the last year about the H5N1 avian flu virus and the threat that this pathogen may lead to a global human pandemic. Now a faction of biomedical researchers is asking if the threat is really that serious. They do agree that a major flu pandemic is likely to occur sometime in the coming decades and that defenses should be set up, but they wonder if H5N1 is the bogeyman that it is being made out to be. If it turns out that it isn't, the public may feel future warnings of dangerous flu strains can be safely ignored. Peter Palese of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City suggests that there is "some hysteria" over H5N1, and adds that though the virus may lead to a human pandemic, that isn't "as much of a certainty as some of my colleagues make it seem."

Of course, H5N1 has had devastating effects in the poultry industry, with about 150 million birds culled worldwide since 2003. The disease has afflicted a number of poultry workers and others who deal closely with birds, with 64 of the 125 known human victims of the pathogen killed by it. If H5N1 mutates into a form that can be easily transmitted from human to human, it could cause immense suffering around the globe.

But will it? Paul Offit -- an immunologist and virologist at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia and University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine and a prominent defender of vaccination -- points out: "The virus is clearly not highly contagious among mammals, and I just don't think it's going to be." More controversially, Paul Ewald, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Louisville, Kentucky, believes that if H5N1 mutated into a form that could vectored from human to human, it would become a fairly mild flu.

The designation system for flu strains is derived from the names of two surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). The H protein is more important because it amounts to a "key" that allows the influenza virus to "unlock" a host cell for infection. Offit points out that while flu strains featuring H5, H7, and H9 can infect humans, no pandemic has been identified that featured these strains. H5N1 has been known for about eight years, and in that time it has never mutated into a strain that can jump easily from human to human.

Palese and Offit freely admit that simply because something hasn't happened in the past doesn't mean that it can't happen in the future, but Offit points out that the six pandemics that have occurred since the late 19th century have all been based on H2, H3, and H1 -- which even more interestingly have followed each other in precisely that sequence, with about 68 years between the recurrence of any one of them. Offit cites the late Maurice Hilleman, a flu virologist at the US Army Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in Silver Spring, Maryland, who suggested in 2002 paper that this cyclical period corresponded to the amount of time it took for the original human population that was immune to that family of strains to die off by other causes, leaving a "naive" human population behind that can be attacked all over again. Based on these arguments, Offit speculates that the next pandemic will occur about 2025 and will be based on an H2 family strain.

As for Ewald's belief that a mutant H5N1 virus that could be transmitted from human to human won't be all that deadly, he bases his convictions on the fact that a pathogen that kills off its host tends to destroy the vectors needed to carry it before it can spread too far. He further suggests that the murderous 1918 virus was a freak, that the crowded conditions of the trenches of World War I and field hospitals allowed a particularly dangerous strain to propagate widely when it would have faded out under more normal conditions. Ewald believes that the next flu pandemic will be more like those of 1957 or 1968 -- which were hardly a trip to Disney World, but were certainly not in the same league as the ghastly 1918 pandemic.

Ewald's ideas have gotten press in the mainstream media, sparking off angry rebuttals by critics who say his ideas are merely speculative, and shouldn't be cited as scientific fact. Yoshihiro Kawaoka of the University of Tokyo feels that the data is too sketchy to come to far-reaching conclusions: "We don't know what viruses circulated [among humans] in the past except for the most recent 150 years." He also points out that H5N1 is unusual among avian viruses, having proven highly lethal to birds and continuing to propagate for years, and with the virus so widespread, the likelihood of a dangerous mutation is rising accordingly. Kawaoka feels our level of knowledge of influenza and pandemics has so many gaps that "there is no scientific knowledge to predict anything."

Even the skeptics believe that it is prudent to take defensive measures, keeping track of H5N1's progress and correcting the long-term decline in the world's production capacity of vaccines. H5N1 may not be the killer virus many are making it out to be, but if it's not the real thing, we need to be prepared when the real thing does come along.

BACK_TO_TOP* SMART SENSOR NETWORKS (2): Trying to manually configure a smart sensor computer network with over a hundred motes would be impractical, not merely because of the number of motes but because in many applications the network would be constantly changing. TinyOS supports a dynamic, self-organizing network organized as a hierarchical "tree". When a mote is powered up, it links itself into the network and determines the best path of "hops" through the motes in the network to a server. If motes are added to or removed from a network, the other motes adapt appropriately.

TinyOS was developed at UCB and is in the public domain as "open source" code. It is a very compact real-time OS (RTOS) that is built in a modular fashion; a node only uses the TinyOS modules that it requires, freeing more memory for sensor data. Mote communications and network organization are under the control of TinyOS and a distributed application program. TinyOS also provides power management functions for the motes.

Of course, the next generation of smart sensor networks will feature thousands of motes, with following generations growing by the same order of magnitude. Techniques used to manage a smart sensor network consisting of a hundred motes may not be adequate for controlling one with a thousand. Design of the overall system will need to keep pace with the growth of network size.

Future smart sensor networks will also provide enhanced capabilities, of course. UCB-Intel researchers have developed "TinyDB" software for smart sensor networks that makes the network operate something very much like a database. A user might query a network for, say, motes where the temperature is in a certain range; motes that have temperature sensors and are sensing temperatures in that will respond, with the results plugged into a spreadsheetlike list that gives the locations of the nodes and displays their data.

Manually updating software for a smart sensor network with hundreds or thousands of nodes would be troublesome, and so an automated scheme has been devised that takes its cues from internet viruses and worms. The update is packaged up and passed through the network, "infecting" motes to give them the software update, with the motes then passing the update on to other motes. The process is more controlled than a virus or worm epidemic, however, with the updates performed in a fashion that minimizes network overhead.

This leads to the next concern, of how to protect a smart sensor network from intrusion and attack. We are well past the time where anyone would ask why anyone would want to do this: we know now without question that if a system can be attacked, it will be, sometimes just for the fun of it. TinyOS has authentication procedures to help lock out intruders, but this is a troublesome issue, since it requires distribution of a large number of authentication keys in a secure but convenient fashion. Of course, security is an evolutionary game: attackers evolve their tactics, and defenses will have to evolve to keep up with threats.

Along with man-made threats, the health of a smart sensor network will be affected by hardware and software bugs, corrupt data, and so on. Since smart sensor networks are a new idea, researchers working on them find they pose unfamiliar problems. Work is underway to improve diagnostics and processes for dealing with smart sensor network failures.

Single-chip motes are now available in prototype form. UCB's "Smartdust" chip incorporates a low-power ADC and RF transceiver, as well as hardware subsystems that perform functions previously implemented in a less efficient form in software. The chip's power requirements are very small, giving it a very long battery life, or the ability to run off ambient light or heat. Given such improved technologies, motes will be built into other electronics systems or even packages, linking the world of smart sensor networks to that of RF identification tags. A smart sensor RFID system would be able to track packages from shipment to delivery, with the motes using accelerometers and other sensors to detect if the packages have been moved. This would help pinpoint theft or sabotage.

The prospect of a "wired world" based on smart sensor networks does raise privacy concerns that need to be addressed, but on the whole smart sensor networks should be a benefit to the public. [END OF SERIES]

PREV* THE BLIND WATCHMAKER (10): Richard Dawkins' THE BLIND WATCHMAKER is somewhat out of date in terms of what is known, or maybe better put what isn't known, about the spontaneous origin of life. It is worthwhile to take a diversion through another book, THE FIFTH MIRACLE, by the Australian-British physicist Paul Davies, which gives a good survey of what is known as present.

The big problem with pinning down the question of the origins of life is that molecules don't leave very good fossils, and there's little that can be determined by examining the evidence left in the stones. To be sure, it is possible to show that the Earth's environment did go through changes after life became established, in the form of the introduction of an oxygen atmosphere, and it is also interesting that for the bulk of the history of the Earth following the introduction of an oxygen atmosphere, the Earth's life-forms were single-celled creatures. Multicellular organisms are a relatively recent invention.

Darwin himself was the first to guess at how it all got started by famously suggesting that life might have arisen in some "warm little pond" full of a stew of chemical ingredients, though he admitted that this was a pure speculation and didn't take it any farther than that. Nobody tried to do much more until the 1920s, when the British scientist J.B.S. Haldane and the Russian scientist Alexander Oparin proposed some relatively detailed models for how life might have arisen. Haldane followed Darwin's suggestion directly, postulating the rise of biomolecules in an expanded "warm little pond", which Haldane called the "primordial soup". Oparin started out with a similar environment, but suggested that oily blobs could have led to the creation of simple cellular creatures.

Nobody paid too much attention to the ideas of Haldane and Oparin, mostly because the era's knowledge of biochemistry was so very primitive. However, an American chemist named Harold Urey was impressed and eventually decided to perform a simple test of the matter. In 1953, he set a graduate researcher named Stanley Miller to the task, with Miller recirculating what Urey believed to be a sample of the primordial atmosphere -- consisting of hydrogen, ammonia, and methane -- in a flask that was subjected to electric sparks. After a few weeks of this treatment, organic materials, including the amino acids used to build up proteins, appeared in the flask.

The Miller-Urey experiment was trumpeted up in the textbooks as evidence that the spontaneous origin of life, but that was clearly overstating the case. Hydrogen is a light gas and tends to dissipate into space from the atmospheres of relatively small planets with low gravity like the Earth, and as far as is believed today, the primordial atmosphere was composed of carbon dioxide and nitrogen, which won't produce amino acids anywhere near as easily.

Even the production of amino acids wasn't a big deal. They're easy to make, actually being found in interstellar gas clouds. The process that produces them is exothermic -- it releases energy -- and so it's thermodynamically straightforward. Assembling amino acids into proteins is an endothermic reaction -- it requires energy. That doesn't rule out the self-assembly of proteins, but it makes it much more troublesome to consider. However, the Miller-Urey experiment has its place of honor as the first attempt to actually perform an experiment to investigate the origins of life. It has been followed by other experiments investigating a wider range of conditions that have opened up further possibilities.

* Along with the experiments, various models have been put forward to describe scenarios for the origin of life. One of the central themes to theories of the spontaneous origins of life on Earth is that the complex, self-replicating molecular system of life as we know it was preceded by one or more simpler, less efficient molecular systems that, in good evolutionary fashion, led to the modern system, which in turn drove the parent system to complete extinction.

One of the pioneers in this line of thought was the Scots chemist Graham Cairns-Smith, who postulated that the original system might have been based on crystals of inorganic materials as often found in clays or mud with crystalline compositions. Cairns-Smith suggests that such a system might gradually lead to more complicated systems until the one we know now came out on top. The dominance of the DNA-based system meant that all the earlier systems disappeared, unable to compete.

The Cairns-Smith idea has its attractions. Everybody knows that crystal structures can grow spontaneously, and it's no jump to think they might be able to achieve higher levels of complexity. Not all think his particular model is credible, but his basic approach has been inspirational.

Another approach, with its roots in the 1960s with Leslie Orgel of the Salk Institute in the US, postulates a pioneering molecular system based completely on RNA, DNA's "partner" molecule, that eventually gave rise to the DNA-based system. The DNA-based system inherently requires both DNA and proteins to work, since DNA requires proteins to catalyze its replication, but RNA is capable of acting as an (admittedly inefficient) catalyst itself.

Intriguing test-tube experiments show that a system of replicating RNA molecules will actually evolve to nullify the effects of a toxin that jams up their works, just as bacteria will evolve to nullify an antibiotic. In other experiments, competition between the replication of different strands of RNA led to a natural selection process, in which one type of RNA, stripped down to its absolute minimum, ended up predominating. Even more intriguingly, test-tube experiments show that if the components of RNA are mixed in solution with a metal to act as a catalyst, they will slowly form up full RNA molecules.

Even the scientists who conducted these experiments admit they are contrived and, in terms of what could have happened in nature, not very realistic. They don't provide any solid proof of the spontaneous origin of life, they just suggest that it's not such a wild idea as it might sound at first. More recent experiments with RNA have made the idea sound ever less wilder.

There have been other suggestions about the spontaneous origin of life, for example that it began with small self-replicating proteins. Right now there's no consensus on the matter, but there's no shortage of interesting ideas and researchers are feeling increasingly optimistic. [TO BE CONTINUED]

START | PREV | NEXT* DOCTOR ROBOT: The growth during the 1990s of "laparoscopy" -- surgery using a camera-tipped probe and extended surgical tools, inserted through small incisions in the body -- was a medical revolution, allowing surgeries to be performed with far less trauma and side effects. The approach was obviously well suited to automation; a NEWSWEEK article ("Cutting Edge" by Jennifer Barrett, 12 December 2005) shows that the combination of laparoscopy and robotics is now well established.

The pathfinder for the technique is the Intuitive Surgery "da Vinci" robotic surgery system, which was approved by the US Food & Drug Administration (FDA) in July 2000; so far it is the only robot surgical system that the FDA has approved. Over 350 da Vincis have been sold -- at $1.3 million USD each -- to the end of 2005, with about 36,600 robotic procedures performed in 2005. The number of procedures is expected to double in 2006.

A patient going "under the knife" on the da Vinci operating table might be forgiven for finding it a bit intimidating, the setup suggesting something like an examination room on a UFO. There are three robot arms -- one tipped with a dual / stereo camera and tiny spotlights, two that are fitted with surgical tools such as forceps, scissors, and scalpel. A surgical assistant fits the proper tool and keeps an eye on the patient; the surgeon is actually across the room, peering inside the patient using a color dual / stereo display system that gives a magnification-10 view of the interior. The surgeon controls the movement of the arms with twin hand controls, using a "dejitter" function when necessary to reduce vibration, and performs other operations -- camera focus, electrocautery, and disengaging the tools -- with foot pedals.

The da Vinci has hit it big in prostate surgery, with 20% of all prostatectomies performed in the US in 2005 handled with the machine. It only requires five tiny incisions, and patients are up and around in days, even gradually regaining full sexual function -- a dodgy thing with traditional methods. The da Vinci is now being used for other operations, even heart bypass surgery.

While few have any doubts that, at least once procedures have matured, the da Vinci is superior to most traditional surgical methods, the high price and complexity of the system is an obstacle to acceptance. There are those who also think it will result in more surgeries than would have been recommended in the past, both to pay off the expense and because it makes surgeries easier on the patient. However, it is clear that robot surgeons are here to stay, and will only continue to become more sophisticated and effective.

BACK_TO_TOP* PUMPING OIL: The rapid rise of oil prices over the last few years has of course been good news to some of the population, including -- as described by an article in THE ECONOMIST ("Jacking Up", 19 November 2005) -- makers of oceanic oil rigs. There's effectively only two, Keppel and SembCorp Marine, both in Singapore. After the end of the last oil crisis, US and European shipyards dropped out of the business, but the Singaporean government felt the need to keep the city-state deeply involved in marine services. Right now that decision is paying off: Keppel and SembCorp Marine have about $7.6 billion USD in orders for rigs -- including "jack-ups" and "semi-submersibles" -- and don't expect to get the orders fulfilled until 2010 at earliest.

A related article on BBC.com reports how oil pumps are at work again in the Los Angeles area. The region is dotted with the pumps -- called "nodding donkeys" because of their rocking action -- but they were shut down in the 1980s with the fall of oil prices. The oil rigs actually predate Los Angeles in the modern sense; some like to say that "they ruined a perfectly good oilfield by building a city on top of it." Now the oil pumps and rigs are being started back up, and improvements are being implemented. Some near-offshore rigs are camouflaged as little tropical islands, complete with palm trees and waterfalls.

* ED: The little Beeb article brought back a strange memory of the early 1960s, when our family went to Disneyland. I have the vaguest and very surreal recollection of seeing the pumps -- I call them "hammerheads" myself -- rocking up and down as we drove through the twilight. It seemed like an odd sort of thing to have in a big city.

I didn't return to Disneyland until I went there for a tradeshow in the late 1990s, and took a day off to circuit the theme park. I was at the Matterhorn Bobsled attraction, which I believe was the world's first steel roller-coaster, and told an attendant that the last time I had been in Disneyland that attraction hadn't even come on line yet.

* CLEAN COAL: The notion of coal as a major supply of energy gives forth images of steam locomotives pouring out soot as they roll down the track, and dark satanic mills. According to a BBC.com article ("How Coal Is Cleaning Up Its Act" by Mark Kinver), the reality is more complicated.

Anyone who knows anything about modern energy technology realizes that coal-fired power plants are a major source of energy. That's not very surprising: there's a lot of coal, and it's cheap. According to the World Coal Institute, the reserves of fossil fuels, given current rates of production from currently known reserves, amount to:

coal: 164 years gas: 67 years oil: 41 years

Coal still has a dirty image, and there was a time in the 1990s that clean-burning natural gas was being pursued as the "better idea". However, rising energy demand has pushed coal back onto center stage. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that coal use will ramp up by 1.4% a year until 2030, when yearly demand will amount to 7.3 billion tonnes, a billion tonnes more than the present.

China is building coal-fired plants at a staggering rate, with about 55 gigawatts (GW) of new production coming online in 2005, most of it in the form of coal-fired plants. China expects to have at least 900 GW of capacity by 2020. Says one IEA official: "If you are in China or India where you have huge resources of coal, and you have elements of the population that do not have access to electricity, then your driver is to build and operate power stations as quickly and as effectively as possible."

Since coal looks like it's going to be around in a big way for some time, the question becomes one of not whether we burn coal, but how. The answer is "clean coal technology (CCT)". CCT is generally interpreted to mean converting coal to a gas for burning to drive a power turbine -- as opposed to the traditional scheme of burning coal to produce steam from a boiler -- with the carbon dioxide and other emissions "sequestered" underground.

However, traditional boiler technology has been improving rapidly, and can now rival "gasification" in terms of efficiency and cleanliness. The latest "supercritical" boiler systems have an operating efficiency of 42%, compared to 30% for traditional boilers. Higher efficiency means burning less coal to get the same amount of power, and so fewer emissions. The latest boilers also allow biomass fuel to be added to the fuel mix, bringing in an element of "renewable" energy to coal power production.

Each approach has its partisans. Gasification advocates point out that modern gasification systems, such as "Integrated Gasification Combined Cycle (IGCC)", can be used for "poly-generation": the gas can be burned to generate power immediately, or piped off and stored for later use in vehicles or industrial plants. Supercritical boiler advocates point out in return that the technology is available now, and can be retrofitted to existing coal-fired power plants at a fraction of the cost of building a new coal gasification plant.

Of course, with either approach the result of combustion is carbon dioxide (CO2), which could contribute to global warming, but enthusiasts believe CO2 can be sequestered underground. The US is spending a billion USD on the "FutureGen" program, which will build a demonstrator plant with IGCC and CO2 sequestration. Critics are not quite convinced yet, and the advocates know they have some proving to do.

* As a footnote to this article, in a clean coal plant using IGCC, the coal is first placed through a tumbler washer to remove surface impurities. The coal is then pulverized and fed to a "gasifier", where it is heated and combined with oxygen and steam to produce "syngas", which is mostly hydrogen. The process generates slag, which has to be removed from the gasifier and disposed of. The syngas is cooled and cleaned, then burned to drive a power turbine. It can also be burned to drive a steam-driven turbine, or stored for use, as mentioned, with vehicles or industrial plants.

In current coal-fired plants, a number of methods are used to eliminate "flue gas" emissions. A "wet scrubber" can be used to perform "flue gas desulfurization", eliminating up to 99% of the sulfur dioxide (SO2) in the flue gas; SO2 tends to be transformed into sulfuric acid in the environment and is a major contributor to "acid rain". In the wet scrubber, the flue gas is sprayed with water and calcium carbonate, which is transformed into gypsum (calcium sulfate). The gypsum can be used to fabricate drywall for the construction industry.

Another pollutant is "NOX" -- nitrous oxide -- which is due generally to incomplete combustion. New "low-NOX burners" restrict the amount of oxygen flow to the hottest part of the combustor, reducing the creation of NOX.

Finally, coal burning produces particulates, such as soot. They can be removed by an "electrostatic precipitator", in which an electrical charge is induced on the particulates, which are then trapped by electrically charged plates. Fabric filters and wet scrubber systems can also be used to deal with particulates.

BACK_TO_TOP* HOT & COLD: The weather is a notoriously complicated physical system; the well-known concept of the "butterfly effect" was originally invented to describe the contrariness of the Earth's weather system, suggesting that the motion of a butterfly's wings in China could lead in time to tornados in Texas. According to a NEWSWEEK article ("Is Europe Due For A Big Chill?" by Michael D. Lemonick), one of the contrary effects of global warming may be to make Northern Europe much colder. Few realize that London is well north of Montreal; the fact that the winters in the UK rarely look much like those of the northern parts of Canada is due to the presence of the "North Atlantic Current", a spur off the warm Gulf Stream that cycles around the Atlantic to the south.

In 2004, Britain's National Oceanography Center set up a network of 22 moored strings of undersea instrument across the North Atlantic, roughly along the latitude of 25 degrees north, between northern Africa and Florida. Each string held current meters and a sensor package that crawled up and down the string on a two-day cycle. The results of the study have now been published and suggest that the currents that drive the Gulf Stream have slowed about 30% since 1992.

Global warming is suspected as the culprit because it results in melting of sea ice, which contains pure water and so dilutes the salinity of the oceans. That would make it harder for cold water to sink and form the return currents needed to keep the oceanic "conveyor belt" operating. The concept is not new: in the 1980s Wallace Broecker -- a geophysicist at Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory -- came up with the notion to explain why Greenland's temperatures dropped precipitously several times over the last 70,000 years.

Once again, the Earth's weather is a complicated thing, and nobody has all the pieces of this puzzle. Computer models show that a shift in oceanic currents and attendant changes in the climate won't happen overnight, and there is some skepticism among climatologists that the rate of change reported is for real. Researchers say there is no need to get panicky. However, the matter certainly deserves further examination.

* POLAR SHIFT: The Earth's fluid core acts as a dynamo, with the rotating electric currents generating a magnetic field that causes compasses to point north. Almost everyone knows that the magnetic poles aren't on the same site as the true poles, on the axis of the Earth's rotation; what is a bit more surprising is (as reported by a BBC.com article) that the magnetic pole is drifting rapidly. The north magnetic pole currently resides in Canada's far north, but within 50 years it may be in Siberia. Some researchers suggest that the current polar shift may be part of a normal oscillation.

Researchers can determine the location of the poles in the past from magnetized materials in sedimentary deposits. Over the last thousand years, the north magnetic pole has wandered repeatedly between northern Canada and Siberia, though it has made a few excursions in other directions as well. Over the past 150 years, the north magnetic pole wandered 1,100 kilometers north and has decreased in intensity by about 10%.

The fluid motions in the Earth's core are chaotic and can change in unpredictable ways, affecting the Earth's magnetic field. Every few hundred thousands of years, the magnetic poles actually reverse. The gradual weakening of the field suggests to some researchers that another polar flip is in progress as we speak. The average time between polar flips is 250,000 years, but it's been about 750,000 years since the last flip, so we're statistically overdue. It may take thousands of years to complete the transition, but other than rendering magnetic compasses useless for the duration, the temporary loss of magnetic field should cause no problems for life on Earth. After all, it's happened plenty of times before.

* SPARE SECOND: According to SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN ("Wait A Second" by Wendy M. Grossman, November 2005), the year 2005 was a bit longer than normal, since a "leap second" had been factored in to keep the clocks in tidy synchronization with the Earth's rotation, which is not only slowing down but does so irregularly, due to complex effects of tides, turbulence in the Earth's core, and shifts of water around the Earth's surface.

The 2005 leap second wasn't that unusual; 22 have been added since 1972, on December 31 or June 30. However, the practice is beginning to become controversial. Since most households might be doing well to keep their clocks accurate to the minute, most citizens don't notice the leap second, However, a leap second can cause "hiccups" in such things as the Global Positioning System (GPS) satellite network and real-time software. What makes leap seconds particularly troublesome is that they don't occur on a regular basis, and they are also implemented at the same time everywhere around the world, causing glitches in say, stock market systems during peak trading hours.

The alternative to leap seconds is to simply perform an overall adjustment once every century or so. Astronomers are not happy about getting rid of the leap second, since they want to be able to point at the same target at the proper time, night by night. However, some astronomers shrug, saying that it wouldn't be difficult to factor out leap seconds in their own software. The International Earth Rotation & Reference Systems Service (IERRSS) is now considering the change.

BACK_TO_TOP* SMART SENSOR NETWORKS (1): As discussed in an article in SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN ("Smart Sensors To Network The World" by David E. Cutler & Hans Mulder, SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN, June 2004), the development of computer networking has had an impact on sensor technology. It is now commonplace for factories or comparable systems to feature networked sensors systems, with sensor "nodes" on the network communicating with each other and with central controllers to do their work.

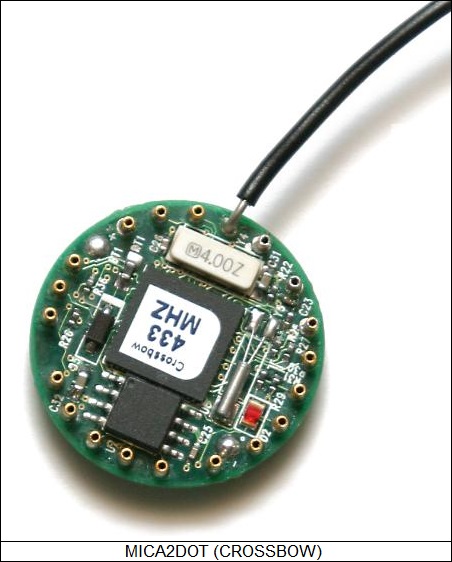

The same concept can be applied to a much wider range of environments. A collaboration between researchers at the University of California at Berkeley (UCB) and Intel Corporation has resulted in the development of "smart sensor" technology that can be used to implement a sensor network to monitor, say, an ecosystem. Each of the battery-powered nodes, or "motes", in the smart sensor network is autonomous, featuring its own processor, analog-to-digital converter (ADC), and a radio frequency (RF) transceiver for communications with other motes. The motes are designed to be cheap but rugged, protected by a tough plastic shell. Each mote is controlled by an operating system named "TinyOS"; on power-up, TinyOS directs the mote to get in touch with its neighbors and establish its networking links. The network is robust, able to work around motes that break down.

For an example of such a smart sensor network in operation, in 2002 a smart sensor network that eventually totaled 150 motes was set up on Great Duck Island, off the coast of the US state of Maine, to help biologists monitor the population of about 18,000 petrels that roost in burrows there during the summer. The motes in this case had to monitor "micro-environmental" conditions such as temperature, humidity, and atmospheric pressure, and also track the presence of birds and chicks using passive infrared sensors. The mote had to be small. The original mote designed by the UCB-Intel team, the "Mica", was smaller than a pack of cigarettes, but still too big for this application. Further work led to the "Mica2Dot", about the size of a large coin.

Since solar cells would have been too big for the mote, and of course in this case the mote was placed in a burrow and couldn't get direct sunlight anyway, lithium battery power was used. Even using micropower processors, operating at just a few percent of the clock rate of a typical power-hungry processor in a desktop PC, and other low-power components, the mote would have drained a battery within a few days, and so the mote spent 99% of its time in a "sleep mode", with all systems shut down except for a timer that provided a wake-up call at a specified interval. The mote checked for network radio communications several times a second and took sensor readings once every few minutes, remaining asleep the rest of the time. Data readings were normally buffered up in memory and only sent when needed, in a compressed format, to reduce communications overhead.

The Duck Island smart sensor network, which its inventors called a "macroscope", was something of an operational prototype, used to validate technologies and processes. A more recent smart sensor effort involved setting up 120 motes in a redwood forest near Sonoma, in northern California. Placement of the motes required some care, since their range is only about 30 meters (100 feet) under optimum conditions, and a redwood forest was by no means an optimum environment for unobstructed radio communications. Some motes were placed simply to act as relays. The motes all ultimately dumped their data into a central server node that radio-relayed the information to UCB, 70 kilometers (43 miles) away.

Other potential applications of smart sensor networks include monitoring factory processes, orchards and other agricultural sites, and buildings or other structures. The military is very interested in the technology. One scheme, being developed by the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and Vanderbilt University, envisions a smart sensor network set up in an urban combat environment. The motes would listen for gunshots and determine the position of shooters. Another scheme being investigated by DARPA involves antitank mines built as motes. The antitank mines would be able to crawl around, deploying or redeploying themselves in the most optimum pattern. [TO BE CONTINUED]

NEXT* THE BLIND WATCHMAKER (9): There's plenty of reason to feel confident that modern evolutionary theory can account for all the diversity of life, but that still leaves one big question unanswered: How did it all get started? The molecular machinery of even the simplest bacterium is, to put it simply, hideously complicated. That leads to Richard Dawkins' next point: Could this complicated system have arisen spontaneously? Just how likely is that? Some claim it is so improbable that life could have only arisen through a supernatural event, that is an event that cannot ever really be explained.

In fact, we have no basis for determining just how likely the spontaneous origin of life actually is. It may be very likely or not be likely at all. Of all the planets in the Universe, we know of only one that supports life, our own, and it's hard to make inferences from a sample size of one. Life may be common in the Universe, but as far as we know, Earth may be the only planet that supports life. We can't perform a credible calculation of the odds, and any opinions that it's common or that it's not are just that -- raw opinions with absolutely no support in the evidence.

There are scientists, usually physicists, who believe that the emergence of life is inevitable given the right conditions. This belief is based on the general notion that the Earth doesn't occupy a privileged position in the Universe, an idea which has often proved sensible and useful in the past -- once upon a time, people thought the Earth was at the center of the Universe, but we've learned better. There's also the fact that life arose on Earth relatively soon after the planet settled down enough to make it possible; if it hadn't been likely, so the thinking goes, the Earth would have remained barren for a much longer time. However, other scientists, usually biologists, point out that there is little basis in known science for thinking that life is anything but a wild freak accident.

Some advocates have pointed to the notion of "self-assembly" in defense, for example the automatic construction of a neatly symmetrical snowflake, but that's a far reach from postulating the spontaneous emergence of a self-replicating system. It is very simple to write little computer programs to draw more or less realistic snowflakes, but it requires a lot of work to write a program to simulate a living entity in any but the most trivially useless way. A living system contains a certain amount of information about how it is to be replicated and the systems for using that information to perform the replication. It's like the difference between wind chimes and a music box that plays Bach.

Is there life elsewhere in the Universe? We do have an idea that technological civilizations aren't common in our galaxy, since we've performed some fairly extensive radio searches of the sky and found nothing resembling a radio transmission from another planet. It must be added that the radio searches conducted so far aren't remotely comprehensive, and there's also no saying that other technological civilizations are using radio systems. Radio silence indicates a lack of radios, possibly a lack of those capable of building radios, but says nothing about the prevalence of life.

The technology for observing planets in other star systems is likely to be available in a few decades. If we start finding planets that have oxygen in their atmospheres, that would be a pretty good hint that they support life along the lines of our own, since free oxygen tends to oxidize with other elements, removing it from the atmosphere. We only have an oxygen atmosphere because the plants on Earth keep replenishing it.

Anyway, back to the question of whether life could have arisen spontaneously at the molecular level. The British astronomer Fred Hoyle, a noted contrarian, once famously compared the idea of the spontaneous origin of life to the idea that a 747 jumbo jetliner might be assembled by a tornado passing through a junkyard, calculating that the probability of the spontaneous origin of life was 1 in 10^40. While is skepticism may have some basis in reality, his specific calculation of the odds was a joke, since he was calculating the probability of an event when he had no substantial information about the nature of the event.

The genetic algorithm discussed earlier in this series was able to perform in seconds what a brute-force search would take up to 175-plus years to work out. Extend the string submitted to the program to a mere 28 characters and the likelihood of simply guessing the right string will jump to 1 in 27^28 = 1.2E40, effectively the same as Hoyle's number. With a million tests per second, the worst-case brute-force search would take 3.8E26 years, which is 2.7E16 times the age of the Universe. The program will make short work of it.

The probability of the creation of a salt crystal 10 atoms on a side is, given the assumption of random assembly, (2^1000)/24 = 4.17E300. The reality is that the rules of chemistry ensure that such a tiny salt crystal is perfectly ordinary. Calculating the probability of life arising by a supernatural event would be amusing; the probability could be calculated on the basis of the rate at which supernatural events are provably known to occur, which is ZERO. The exercise would have to be for entertainment value, but it would at least have the virtue of being silly on purpose. [TO BE CONTINUED]

START | PREV | NEXT* TERROR AS BUSINESS: The emergence of global Islamic terror over the past few decades took the world somewhat by surprise, and it has taken time to acquire an understanding of the threat. One interesting aspect, discussed in a US NEWS & WORLD REPORT article ("Paying For Terror" by David E. Kaplan, 5 December 2005), is the linkage between international terrorism and international crime.

At 1:25 PM on 12 March 1993, a bomb went off in the Mumbai Stock Exchange. Other explosions and attacks followed for almost two hours at other prime targets in the Indian metropolis. Ten bombs went off in all, with 257 people killed and over 700 injured. The carefully-planned assault was performed by Islamic extremists, in retaliation for riots provoked by Hindu extremists that had killed over a thousand Muslims. The Mumbai bombings were only a sample of what might have been. Indian police soon found a cache of tonnes of explosives, along with large stocks of weapons and ammunition. Then the examination of an abandoned van full of weapons gave the big break in the case, pointing to a gangster boss named Dawood Ibrahim.

The police knew who Dawood Ibrahim was. Everybody in India did. He was a celebrity gangster, simply known as "Dawood" in the news media. One of eight sons of a Muslim Indian policeman, Dawood started out as a petty crook and then worked his way up. By the 1980s his gang, just known as "D Company", mostly staffed by other Indian Muslims, was the biggest and most feared gang in Mumbai. Smuggling was D Company's bread and butter, but Dawood had fingers in everything, including Bollywood movie productions.

Pressure from the law and gang wars forced him to move to Dubai, in the United Arab Emirates, in 1985. Dubai is a gleaming, glittering, modern city on the Persian Gulf, with relaxed rules and a commercial mindset that makes it a hub for commerce from the Middle East to Southeast Asia. That includes, not too surprisingly, illegal commerce. From Dubai, Dawood was able to spread his empire over 14 countries.

The anti-Muslim riots in India in 1993 led Dawood to help Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), the Pakistani intelligence apparatus, smuggle explosives into India. After Dawood's involvement in the attacks became apparent, he jumped to first place on India's "most wanted" list. He fled to Pakistan, where he has continued in command of his criminal empire under the protection of the ISI. He is believed to have complicity in several more attacks by Islamic terrorists in India, and to have had contacts with al-Qaeda operatives.

* Dawood's involvement with terrorism does clearly show that linkages have arisen between gangsters and terrorists, but many authorities say that the two groups keep each other at arm's length. Gangsters generally want to make profits, not strike blows for political and religious causes. Terrorist attacks usually don't make much money, and they attract far too much unwanted attention from the authorities. On their part, terrorists know that gangsters will quickly betray them if there's a profit in doing it, and that too much involvement by "holy warriors" in crime may lead them to gradually become less like holy warriors and more like gangsters.

What is more significant is that terrorist groups are becoming criminal gangs in their own right, funding their movement through drug dealing, product counterfeiting, and human trafficking. The "jihadis" -- Islamic terrorists -- that performed the 11 March 2004 bombings in Madrid supported themselves by selling hashish and ecstasy, with Spanish police seizing large stocks of drugs and money from the group. The Southeast Asian Jemaah Islamiyah group likes credit card fraud, as well as robbing banks and jewelry stores. There is a rising acceptance of such purely criminal activities among the jihadis. It is believed that Abu Bakir Bashir, the alleged spiritual head of Jemaah Islamiyah, put it neatly: "You can take their blood; then why not take their property?"

The authorities in Western Europe see increasing jihadi control over the drug trade in their countries. In Morocco, a major source of hashish sent north, jihadis are believed to control about a third of the trade. Jihadis have a clear attraction to small-scale scams -- credit-card fraud, identity theft, cellphone pirating -- that provide all the funds they need but don't attract too much attention from the authorities. Jihadis also seem to be involved in human trafficking in Europe, though they are not the big players.

Many jihadis got their training in crime in prison. It is believed that up to half the inmates in French prison are Muslims, and in that environment zealots come into contact with criminals who can give them ideas. Jihadis can also form networks during their prison days that persist once they get out into the world again.

Afghanistan has proven to be another meeting ground between criminals and terrorists. Although Osama bin Laden has discouraged his followers from getting involved in the Afghan heroin trade, other Islamist groups in the region aren't so cautious. It is an enormous business, with drugs flooding into neighboring countries, breeding junkies and corrupt officials. Even arch-conservative Iran has been afflicted, with high rates of addiction and evidence of collusion with drug traffickers at high levels of government. The penetration of the trade into the former southern Soviet republics leads to an unpleasant prospect of two-way trade: heroin for sophisticated Soviet weaponry that could be used in terrorist attacks, such as man-portable anti-aircraft missiles or even nuclear munitions.

In Iraq, it is almost impossible to distinguish between gangsters and insurgents. Kidnappings for ransom are commonplace. Corruption is common, and it is now becoming apparent that money provided by the US government is ending up in the hands of insurgents to perform attacks on American forces and Iraqis.

* Criminal activities have downsides for the jihadis. As mentioned, a life of criminal profit can undermine radical dedication, and bring jihadis into linkages with criminals who don't hesitate much to sell them out. Crimes also attract attention to jihadi groups, and give more opportunities for getting caught. An alleged jihadi group in California that was sticking up gas stations was nailed when one of their number left his cellphone at the scene of the crime. A local cop found it.

Internationally, law enforcement organizations around the world have been able to pull in some big fish in international crime, but the division between criminal investigation and antiterrorist operations has made matters more difficult. There are efforts to improve coordination, but there is a real difficulty in that domestic criminal investigation agencies have a necessary separation of powers from international intelligence agencies.

As for Dawood Ibrahim, he appears to be suffering from the effects of his own notoriety. The shrewdest gangsters learn to keep a low profile; but everyone knows who Dawood is, and that makes him an international target. US law-enforcement agencies have been pressuring Pakistan about him. Although the Pakistanis officially deny that he is even there, he may be becoming more of a liability than an asset to his hosts. There is an outstanding Interpol warrant for his arrest, which makes it difficult for him to transfer his operation elsewhere. The authorities are looking forward to the time when they will be able to reel him in.

BACK_TO_TOP* IRAQ EXIT: Over what is now going on three years, the US invasion of Iraq, which seemed to start out as a spectacular success, has gone from one calamity to the next, while members of the Bush II Administration attempted to reassure that public that all was well. Right now, given the dismal history, even conservatives have good reason to be less than optimistic.

It is now clear that administration's plans for regime change in Iraq, to put it tactfully, lacked realism. However, an article in NEWSWEEK magazine ("The New Way Out" by Michael Hirsch, Scott Johnson, and Kevin Perano) suggests that, finally, there may be grounds for cautious optimism: the Bush II administration seems to be piecing together a workable strategy to get American soldiers out of Iraq without leaving chaos behind. The fact that NEWSWEEK is no particular friend of the administration gives the article some credibility.

Last spring, things were so out of control in Baghdad that even driving from the airport to the Green Zone was a "Mad Max" adventure in terror. However, since that time special checkpoints, manned by a few dozen Iraqi Special Police and backed up by two Iraqi National Guard infantry platoons, have turned the notorious "Ambush Alley" into, at least by Iraqi standards, a peaceful lane. The key was getting rid of checkpoints manned by American soldiers; as US Army officer involved put it: "It would have simply produced more targets."

Of course, the Baghdad airport road is only one small piece of a big country, and violence continues at full burn, with American soldiers killed every week and far more Iraqis killed every day. Still, it does seem that the administration has a real blueprint: suppress the insurgents and pass control over to Iraqi forces, while handing carrots to Sunni leaders to get them to stop supporting the insurgency. To ensure US domestic support, American troops are to be slowly drawn down, hopefully to less than 100,000 by the time midterm 2006 elections roll around.

The troop drawdown is not entirely driven by the need to maintain public support; it is also completely obvious that the presence of US occupation forces is a major provocation that keeps on fueling the insurgency. That leads to the obvious question of why the US simply doesn't pull out now.

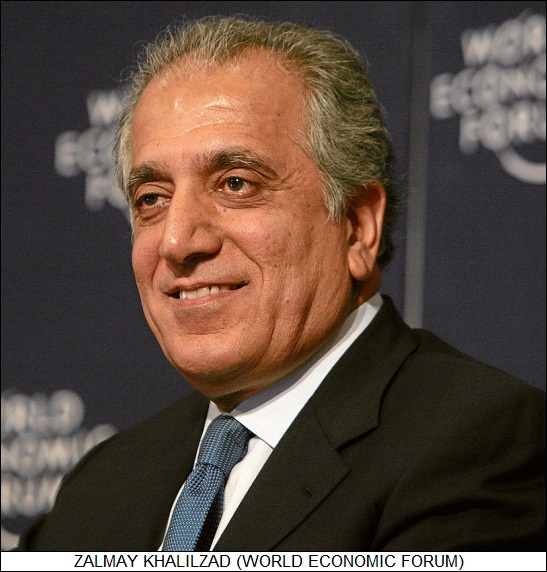

Zalmay Khalilzad, the highly respected Afghan-born US ambassador to Iraq, has the answer: "People need to be clear what the stakes are here. If we were to do a premature withdrawal, there could be a Shia-Sunni war that could spread beyond Iraq. And you could have Iran backing the Shias and Sunni Arab states backing the Sunnis. You could have a regional war that could go on for a very long time, and affect the security of oil supplies. Terrorists could take over part of the country and expand from here. And given the resources of Iraq, given the technical expertise of its people, it will make Afghanistan look like child's play." The US Army War College put the matter neatly in a refreshing bit of military directness: "We can't stay, we can't leave, and we can't fail."

Since pulling out troops completely is not practical over the short term, the current concept is to pull most of them out of sight in rear-area bases where they can deploy to provide heavy firepower when needed. The normal frontline military presence will consist of special operations teams, officer-advisers, and reconstruction specialists working discreetly inside Iraqi units. Ambassador Khalilzad is working on the creation of "provincial reconstruction teams (PRTs)" made up of both civilians and soldiers, with up to 100 personnel.

There are about 160,000 US troops in Iraq, now focused on providing security for elections. About 22,000 will leave early in 2006; optimistically, 20,000 to 30,000 will be gone by midyear; and troop levels should be under 100,000, even well under that limit, by the end of 2006. Getting the troops out means swallowing some bitter medicine, for example coming to terms with Iran, once described as a charter member of the "Axis of Evil". Khalilzad had quiet talks with the Iranians while he was ambassador to Afghanistan after the overthrow of the Taliban regime, and he plans to meet again with Iranian officials. It's hard to imagine two much more antagonistic groups on the sides of the bargaining table, but the US and Iran have common interests in Iraq. The US wants a democratic Iraq, which means to Iranians that their Shiite Iraqi brethren will carry a great deal of weight in the new order.

Nothing is guaranteed to work; there is much violence, chaos, corruption, and treachery in Iraq. If the Iraqi National Guard won't fight the insurgents, things cannot possibly work out. Worse, since the Iraqi National Guard will take time to build up a logistical support apparatus, it will be dependent on US military support units for some time, and those US soldiers will be dependent in turn on the protection of the Iraqi National Guard. The insurgents have also proven adaptable, and have done much to frustrate attempts to improve Iraq's stability.

BACK_TO_TOP* SUPER SHIPS: Transport of goods over the world's oceans by freighter vessels is something that most people know about but generally take for granted. A BBC.com report ("Ships Power Into Faster Future" by Tracey Logan) shows that international maritime shipping is now growing rapidly and in a state of rapid change.

One observer points out that about 90% of the world's trade goes by sea, and that the amount of goods shipped may well double in the next few decades. One of the biggest drivers of change is the increasing presence of China in world markets. Ships have to carry the flood of goods from China to other nations, with the volume steadily increasing. The rise in the importance of shipping means bigger, faster, and greener ships.

The world's biggest container ship, the MSC PAMELA, launched in 2005, can carry 9,200 containers on the route between China and Western Europe. A few decades back, such a huge ship would have been unthinkable, but supersized container ships are now becoming the norm. A new container ship, the EMMA MAERSK, is in the works and will be able to carry 11,000 containers. By 2020, almost a third of the world's container ships will be too big to fit through the Panama Canal.

The government of Panama is considering a plan to widen the canal. The ultimate size limit is believed to be about 18,000 containers, since any vessel larger than that would have too deep a draught to pass through the Straits of Malacca, the chokepoint between the Pacific and Indian Oceans. However, nobody thinks container ships will get near to that big, since above about 12,500 containers, no port would have the capacity to load and unload them in any reasonable fashion.

* The economy of scale provided by container shipping means that it only costs a US dollar or so to ship a refrigerator across an ocean, but there is a drawback. A big container ship can only steam at about 25 KPH (16 MPH), and it takes about a month to deliver an automobile from the factory in Europe to a customer in the US. That isn't a problem in many cases, but a naval architect named Nigel Gee thinks that there is definitely a place for a fast cargo transport that can get a car across the Atlantic in a week, at higher cost than normal shipping but much lower cost than air freight. Gee's "Pentamaran" design will carry 1,000 containers at a speed of about 85 KPH (53 MPH). It features a torpedolike main hull, with twin thin side hulls on each side to provide stability.

The other factor in cargo ship design is of course fuel economy. The British and French defense ministries are now conducting an "All Electric Ship Demonstrator" project, with gas turbines providing electricity for an electrically driven propeller that doesn't need a long and heavy shaft and is computer controlled to eliminate the need for a rudder. The electric drive makes the prop far more efficient and agile; coupled with improved ship design, shippers would be able to save considerable amounts of fuel.

Some naval architects even believe that future cargo vessels may be nuclear-powered. There were attempts in the past to build nuclear-powered commercial vessels, but they weren't economical, particularly because they weren't welcome in many ports. Whether there will be huge, nuclear-powered container ships remains to be seen.

* REDISCOVERING EFFICIENCY: Lulled into complacency by a long period of low gasoline prices, both American consumers and the US automobile industry were caught by surprise when gas prices shot up over the past few years. Consumers had demanded big sports-utility vehicles (SUVs) and Detroit had built them in response, but SUV sales have now crashed. Although foreign competitors had also built SUVs, they hadn't ignored fuel efficient vehicles either, and they have been better able to take advantage of the new order.

According to a NEWSWEEK article ("Go The Extra Mile" by Keith Naughton, 21 November 2005), Detroit has learned the lesson. US car makers are working on hybrids, but they're too expensive to capture much of the market, and so the real push is on making conventional automobiles more efficient.

One of the big buzzes these days is "displacement on demand (DOD)", in which an engine only uses the cylinders it needs to keep the car rolling. In other words, a car with a V8 engine would run on four cylinders when it was cruising down the highway. GM actually tried this idea during the last gas crisis a quarter-century ago, but the Cadillac "8-6-4" engine was a disaster, proving very unreliable.

There has also been some push towards "continuously variable transmissions (CVTs)", but though they are in theory a good idea, capable of cutting fuel consumption by 10%, there has been resistance to them, some drivers complaining that they are noisy, shaky, and have a tendency to shift in a fashion that seems unnatural and aggravating. Chrysler is retuning their CVT to act more like a regular transmission, but for the moment the push is on a more conventional six-speed transmission that can give similar economies.

Automobile makers are now researching "homogeneous charge compression ignition (HCCI)", in which the spark plugs are eliminated and simple compression is used to ignite the fuel-air mixture, much like in a diesel engine. This could improve fuel economy by 30% or more and burns clean, but right now the scheme doesn't work well on cold start and at high speeds. One idea is a dual-mode engine that uses spark plugs only when needed.

Right now, car makers are shipping "variable valve" engines whose valve displacement cycles are adjusted to improve efficiency. Other efficiencies are being obtained from even simpler technologies: a "mileage meter", currently common on hybrids, to tell the driver when fuel economy is optimum; lighter components and assemblies; and in particular streamlining and aerodynamics. Ford engineers have been tinkering with shutters that will block off the front grille at high speeds to improve airflow. Mercedes engineers took a hint from nature and designed a "Bionic" concept car that took its streamlining cues from the appropriately-named "boxfish". Fuel economy is sexy again. Hopefully, this time around the romance will be here to stay.

BACK_TO_TOP* A HISTORY OF BARBED WIRE (2): In 1876, a large Eastern firm named Washburn & Moen bought out Glidden's interest in the Barbed Fence Company for $60,000 USD and royalty payments, and Ellwood became a partner in Washburn & Moen. The new company went to court to establish the priority of the patents and control the competition. The patent fight went on for 16 years, with a good chunk of the profits for the thriving businesses ending up in the pockets of lawyers.

The original patents were attacked on the basis that they lacked originality, barbed wire being nothing more than an artificial equivalent of thornbushes. There was also the issue of who had priority, with sleazy operators fabricating hoaxes of earlier inventions of barbed wire, designing their own patterns of barbed wire and burying them in dungpiles to make them look aged and rusty. In fact, barbed wire had apparently been invented several times in several places in previous decades but hadn't caught on, so there were legitimate priority challenges as well.

The courts ruled in favor of the Glidden patent in 1880. The Washburn & Moen company used the judgement to harass competitors, either forcing them to pay license fees, or driving them out of business. Jacob Haish was a stubborn man, but Washburn & Moen was just too big for him, and he quit the barbed wire business. Making barbed wire was so easy and cheap, however, that product pirates appeared -- typically manufacturing a big batch of "moonshine wire", selling it at a cut-rate price, pocketing the money, and moving on. Their actions were enthusiastically supported by consumers. In 1881, an Iowa farmer's association blasted Washburn & Moen as "the most gigantic and despotic monopoly of modern times."

The Federal government was much weaker in 1880 than it is now, but the courts still didn't like monopolies. However, a monopoly was not legally objectionable if it didn't operate in restraint of trade, and Washburn & Moen's lawyers argued that their organization provided market stability, a consistent level of quality, and economies of scale that benefited the consumer. The US Supreme Court finally judged decisively in favor of the Glidden patent and Washburn and Moen.

In 1898, Wasburn & Moen re-formed the barbed wire organization into the American Steel & Wire Company of Illinois, with the principals controlling a little under half the company. American Steel & Wire controlled 96% of the market and possessed its own mines and railways. Ellwood and the others at the top were all very wealthy, millionaires when a million dollars was a princely fortune and not just a tidy sum. Although Haish and Glidden were generally out of the business by that time, barbed wire had been kind to them as well. Haish proved a generous benefactor to the town of DeKalb, funding schools, libraries, and even an opera house. Glidden opened a grand luxury hotel.