* Entries include: JFK assassination, intracellular immune mechanisms, parasitic wasp genome, history of the pacemaker, silent mutations not so silent after all, advances in optical metamaterials, neural connectomics, extensive amounts of computer code in cars, Craig Venter focuses on algae biofuels & other biofuel efforts, democracy in question, Chagas disease and schistosomiasis, and carbon planets.

* NEWS COMMENTARY FOR MARCH 2010: The Obama Administration finally managed to push a US national health-care plan through Congress this last month. The plan mandates that all Americans will have health insurance, with lower income citizens subsidized by the taxpayers. Insurers will no longer be able to reject applicants because of "pre-existing conditions". Anybody who doesn't get insurance will be fined.

As Vice President Joe Biden put it: "This is a big %$#?&*! deal." It certainly is, but from the sidelines it's a bit hard to know what to make of it. Even advocates admit that the legislation is inadequate, with no provisions for actually limiting health-care cost escalation. However, the critics were in a weak position, since the US health care system is clearly broken and the government had to get involved. Simply going into denial and saying the government should do little or nothing wasn't realistic; like it or not, something was going to be done. For the moment, simply passing the legislation seems to have scored points for the Obama administration with the public, though the resistance continues -- there's talk of challenging the constitutionality of legally coercing people to buy health insurance.

In any case, the US government was already involved in national health care, with Medicare and Medicaid dollars being the single biggest source of funds for the US medical industry, and it defies simple logic to say the government should not have a strong say over the industry when the government's providing so much of the money. The government has made its move, and with the camel's nose in the tent, more of the camel is likely to follow. It's safe to predict that the result will be more or less a nightmare; the only problem is that a nightmare is what we have now, and the question is only whether the change is going to be in the direction of "more" or in the direction of "less".

* Speaking of nightmares, the long-running fiasco over the US Air Force's attempt to obtain a new inflight refueling tanker aircraft, discussed most recently here in 2008, took a somewhat startling turn in early March the Northrop Grumman / EADS team that was offering a tanker based on the Airbus A330 decided to abandon their effort to win the award, leaving the field to Boeing with a tanker based on the 767 or 777 jetliners.

That was surprising since there was so much money at stake, but apparently the Northrop Grumman / EADS team decided that there was no way they were going to win the way the politics were going; and even if they did get the award, it would be challenged again. The obvious conclusion was that it was futile to keep throwing away their resources chasing after a carrot that would always remain out of reach. Some observers believed this left the USAF with an inferior solution that only existed on paper, but there's no particular reason to think the service will be particularly worse off with the Boeing product, which is mostly based on existing technology. Boeing already sells 767-based tankers, and the USAF solution is essentially a different mix-and-match of tech already in hand.

However, the failure of the competition is an embarrassment for the US government that will taint relations with Europe. It cannot really be blamed on the Obama Administration since the program and its rocky history go back so many years, but the Obama Administration now has to rethink defense procurement policies so the same thing doesn't happen again any time soon.

As lousy as the deal is, it looks like it's what everyone's just going to live with: EADS walks away, Boeing picks up the pot, the Air Force accepts the solution, and the State Department tries to placate irritated Europeans. Well, at least Boeing won't have any problem with it -- and no doubt Air Force brass are relieved to finally have a resolution to an endless fiasco, even if it's not a perfect one.

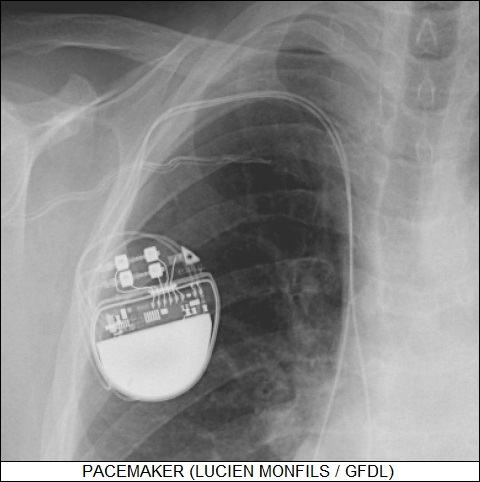

COMMENT ON ARTICLE* A HISTORY OF THE PACEMAKER: As discussed in an article from THE ECONOMIST ("The Rhythm Of Life", 5 March 2009), in 1889 John Alexander MacWilliam, a young Scots physiologist, discovered that he could control the heartbeat of a cat. Using a metronome and a needle electrode inserted into the cat's heart, MacWilliam found that he could speed up and restore normal heart rhythms by applying timed electrical shocks. That might have seemed like a somewhat sadistic experiment, particularly to cat lovers, but a half century ago MacWilliam's research led to the first implantable heart pacemaker, which was followed a few decades later by the implantable defibrillator. Now the "heart rhythm management" industry is big business. The basic principles of the technology haven't changed over the decades, but smaller, smarter devices promise to be easier to implant and provide more precise control over the pacing of the heart. The list of conditions that can be addressed by implantable pacemakers and defibrillators keeps growing, with more than a half million patients fitted with them every year.

The first patient to receive a fully implantable artificial pacemaker was a 43-year-old Swede named Arne Larsson. He was facing death from a heart condition; his wife, Else-Marie, had heard about cardiac pacing technology being tested on animals, and decided to see if she could save her husband's life. Else-Marie convinced Ake Senning, a surgeon at the Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm, and Rune Elmqvist, a medically trained engineer, to build an implantable pacemaker for Arne. What did he have to lose?

The initial prototype was built in Elmqvist's kitchen and was implanted in Arne Larsson on 8 October 1958. It only lasted three hours, but the next morning Larsson was fitted with a second, identical device that lasted two days. Larsson became the "leading edge adopter" of pacemaker technology, being implanted with a total of 26 up to his death at age 85, from causes unrelated to his heart condition.

* An artificial pacemaker works by restoring the function of a faulty "sinoatrial node", the heart's normal pacemaker. Normally, the sinoatrial node produces steady electrical pulses that spread across the heart, causing it to beat in synchrony. When the sinoatrial node malfunctions, it can produce dangerously slow or erratic rhythms. By inserting electrodes into one or more of the chambers of the heart, via a large vein, it is possible to mimic the action of the sinoatrial node by applying small electrical shocks at regular intervals. Power leads link the electrodes to a small hermetically sealed metal box, called the "generator", that contains the battery and electronics. Modern generators are slightly bigger than a matchbox.

Arne Larsson's first pacemakers were the size of a can of shoe polish, which is what Elmqvist used as molds for his epoxy-resin generators. However, most pacemakers that followed were well bigger than that. Elmqvist's early device was designed to be recharged from outside the body, using an electrical induction loop, but the need to periodically recharge the generator was judged unsafe, due to worries that patients might fumble the job or forget to do it. That meant packing batteries into the generator that could keep it going for years at a time, and so pacemakers ended up being five times bigger than they are now. Mercury-zinc batteries were selected early on; they could provide power for two years, but they also produced hydrogen gas that could diffuse into the body. As imperfect as the early pacemakers were, they were still a huge benefit: before their development, patients had to be paced by external devices so big they had to be rolled around on carts.

In the mid-1960s, a company named Nuclear Materials & Equipment Corporation, of Apollo, Pennsylvania, developed an atomic pacemaker, using a tiny bit of radioactive plutonium-238 isotope to generate heat through radioactive decay, with a thermocouple converting the heat into electricity. The battery was sealed with three layers of casing that could stand up to a rifle bullet. The design lifespan of the device was ten years. The first atomic pacemaker was implanted in France in 1970. Some atomic pacemakers actually survived for almost two decades, but they had significant drawbacks, even beyond the potential threat to the patient. When a device was removed, it had to be handled as nuclear waste, with disposal being a troublesome and expensive process. Eventually, lithium-iodine batteries provided lifetimes of eight to ten years with no need to worry about disposal of radioactive materials; the new batteries also didn't produce hydrogen or other exhaust gases.

Better power sources also led to a beefed-up version of a pacemaker that could restart the heart or correct "fibrillations" -- irregular or dangerously fast heartbeats. These devices, also known as "implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs)", hit the heart with a shock to get it beating or correct fibrillations. A team of researchers at Sinai Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, began work on the ICD in the late 1950s, with the first ICD implanted in 1980 at Johns Hopkins Hospital by Dr. Levi Watkins.

ICDs are much "smarter" devices than pacemakers, with an ICD using a computer processor chip to monitor heart activity and determine when and how to administer a proper shock. The latest ICDs have wireless telemetry capability that allows doctors to monitor their operation. ICDs are now very popular, and implantation has become a routine outpatient procedure that can take less than a half hour.

* Heart pacemakers and ICDs are one of medical technology's real success stories, and there's room for improvement. The power leads of the implants tend to be the weak link in the technology. There have been recalls due to manufacturing defects, and estimates have been produced that suggest 20% of ICDs will suffer from lead failures within ten years. In one case from Boston in 2001, a doctor was running a routine check on a 79-year-old patient whose IDC exploded during a test, generating a blue flash and a loud pop. The patient, though alarmed, was unharmed. The insulation on a lead had worn away, resulting in a short circuit. That was an unusual failure mode, but there are plenty of others.

Usually lead failures give plenty of advance warning, but replacing the implant itself is dangerous. The ends of the leads are barbed to ensure a secure purchase in the beating heart, and getting them out can be tricky. If they don't come out easily, which happens about once in every 50 cases, the only recourse is open-heart surgery, with a fair chance of killing the patient. Replacing the generator, incidentally, is straightforward, involving only a small incision in the chest, with complications in only about 1 out of 100 operations.

Work is underway to develop implants that don't require leads to be stuck into the heart. A California company named Cameron Health has developed a "subcutaneous ICD (S-ICD)", which features electrodes placed outside the heart, just under the skin, making the device easier and safer to implant or replace. The S-ICD is also less prone to false alarms due to electrical noise. Being on the receiving end of an ICD shock is like being kicked in the chest, and with current ICD technology about a third of the firings are due to false alarms.

Another California firm named EBR Systems eliminates electric shocks entirely, using a generator module that focuses ultrasonic waves on a receiver implanted in the heart that generates a physical shock in response. Details are confidential; company officials say they are only working a pacemaker for the moment, defibrillation having proven too much of a challenge. Researchers at the German Heart Center in Essen are working on a comparable wireless approach, but instead of ultrasound they are using electromagnetic induction to stimulate a receiver implanted in the heart. It took a 70 years to turn MacWilliam's pioneering technology into the implantable heart pacemaker, but in the next 50 years the technology has matured dramatically, and it seems poised for significant advances in the 21st century.

COMMENT ON ARTICLE* ENEMY RECOGNITION (2): Once our cytoplasmic defenses spot an intruder, the cell has several options for response:

Of course, where there are measures, there are likely to be countermeasures, and some pathogens have acquired means to undermine cellular defenses. The hepatitis C virus produces an enzyme that breaks the molecular mechanism by which RIG-I sounds the alarm against the virus, while the bacterium that causes Legionnaire's disease can resist autophagy, and the tuberculosis bacterium has acquired some mysterious mechanism to head off an inflammation response.

* Even though not much is known about our cytoplasmic immune defenses just yet, researchers have still found the knowledge acquired so far to be useful. It has helped deal with the extremely rare "fever syndromes", which afflict a few hundred people worldwide and afflict them with a fever, skin rash, and joint pain if they go outside on a cold day. It turns out that the fever syndromes are due to a mutant NLR gene. This particular NLR, NLRP3, helps promote an inflammation response involving a cytokine named "interleukin-1 (IL-1)". Based on this realization, patients were treated with a drug named "anakinara" that effective disables the immune response provoked by IL-1. Although anakinara was originally developed to treat rheumatoid arthritis, it proved perfectly effective in dealing with fever syndrome.

An improved understanding of our cytoplasmic defenses could also lead to better vaccines. Vaccine mixes often include "adjuvants", which are substances that help promote a strong immune response. The only adjuvant currently authorized for use in the USA is aluminum hydroxide, or alum; it's effective, but it can also cause fevers and other side effects. Recent research suggests that alum can provoke cytoplasmic defenses to produce an inflammation response. Better knowledge of our defenses may lead to the development of adjuvants with fewer side effects.

Finally, it is important that we understand exactly what our immune system, all of it, can and cannot do. Our immune system is a marvelously elaborate mechanism that has impressive capabilities, but it's faced with formidable adversaries. Pathogens can be marvelously elaborate themselves, and their life cycles are far shorter than our own, meaning they have an edge in this evolutionary struggle. Says one researcher: "Because the bugs evolve faster, they are always going to stay a few steps ahead." We need to be able to figure out how to outsmart them. [END OF SERIES]

PREV | COMMENT ON ARTICLE* THE KILLING OF JFK -- LEE HARVEY OSWALD (7): On 25 January 1963, Lee Harvey Oswald mailed off the last installment on his loan from the State Department. Out of debt at last, on 27 January he was able to then send $10 USD in cash to Seaport Traders of Los Angeles to buy a Smith & Wesson 0.38 caliber revolver. The order was placed in the name of "A.J. Hidell"; the form required a witness, with the name filled in as "D.F. Drittal". Later analysis showed both names to be in Oswald's handwriting. The pistol was shipped via Railway Express, with the balance of $19.95 USD plus shipping charges to be paid COD.

By this time, he was becoming persistently brutal to Marina. She stayed with him because she really didn't have anyplace else to go -- she couldn't speak much English and Lee refused to let anyone teach her, she did not want to return to the USSR, and in fact he used the threat of getting her sent home to intimidate her. The fact that she was pregnant again by this time only increased her dependence.

On 14 February, Oswald saw a story in the DALLAS MORNING NEWS about retired US Army General Edwin Walker, a prominent local Rightist who was active in the ultra-right John Birch Society. Oswald talked about Walker to de Mohrenschildt, who expressed no liking for Walker, suggesting to Oswald that anyone who "knocked off Walker" would be doing society a favor.

Later that month, the Oswalds ran into a couple named Michael and Ruth Paine at a dinner party. The Paines were both American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) members, liberal activists in conservative Texas. At the time, the couple was separated and Michael had moved out of the house, but they were on fair terms, with Michael often coming by to play with their two small kids and make himself useful with household errands. Ruth, a Quaker, was trying to learn Russian and took a strong, sympathetic interest in Marina Oswald. The Paines would get to know the Oswalds about as well as anyone ever did.

Conspiracy theorists like to paint lurid pictures of the Paines, proclaiming that they were Red agents or part of a US government conspiracy -- one or the other. One of the particularly bizarre notions circulated by conspiracy theorists about the Paines was the fact that Michael was employed at Bell Aircraft in the Fort Worth area and was supposed to have worked for Walter Dornberger, a German expatriate who was employed by Bell.

Dornberger had led the German V-2 rocket program during World War 2, being the boss of the well-known Wernher von Braun, famous in the 1960s for his work on the space rockets for the US National Aeronautics & Space Administration (NASA) that would put Americans on the Moon. Conspiracy theorists describe Dornberger as a "Nazi war criminal", which is a stretch, if not a really big one -- he was indeed a faithful Nazi and his hands were hardly clean, though Dornberger had never been arraigned for and certainly not convicted of war crimes. Almost the same could be said of von Braun, and there was just as much or as little cause to link Dornberger to a sinister conspiracy as there was to link von Braun to one.

More significantly, there was no close link between Paine and Dornberger other than the fact they both worked for Bell. The Bell Fort Worth plant built helicopters -- it was not surprising Michael worked there, since his stepfather was Arthur Young, inventor of the famous Bell Model 47 "MASH" helicopter, one of the key players in the development of the helicopter, and a prime mover in Bell's helicopter business. However, Dornberger was a rocket and space systems engineer who worked at the Bell plant in Buffalo, New York. A personal relationship between a Nazi and a Left-leaning pacifist seems a bit unlikely on the face of it. Conspiracy theorists have a tendency to grasp at straws and build great houses out of them.

Incidentally, some conspiracy theorists have linked Wernher von Braun to the conspiracy. A "William Torbitt" released a document titled "Nomenclature of an Assassination Cabal" in 1970 that claimed von Braun was the boss of the "NASA Security Division". The document was written in a schizophrenic style, consisting of little more than lists of claims and assertions involving almost everything and everybody in the assassination "cabal", without any pretense of validation or even a coherent story. While some conspiracy theorists have taken it at face value, others have found it so preposterous that they suspected it was actually "disinformation" created by the conspiracy to discredit them. [TO BE CONTINUED]

START | PREV | NEXT | COMMENT ON ARTICLE* GIMMICKS & GADGETS: WIRED.com reported on a transportable water cleaning system the US Army is now deploying to Afghanistan that uses bacteria to purify water. That sounds startling on the face of it, but that's essentially how sewage treatment plants clean up their sludge. However, members of the group at Sam Houston State University (SHSU) in Texas say their system is by no means simply a portable sewage treatment plant. The researchers came up with a mix of common bacteria, found in any handful of dirt, that can purify water in less than 24 hours without producing toxic byproducts, in a system packed in an ordinary shipping container. A sewage treatment plant takes much longer and doesn't do anywhere near as tidy a job. The military definitely has use for water cleaning systems in Afghanistan, where lack of access to clean water means having to haul water to field installations. Of course, such systems have obvious use for disaster relief efforts, with consideration being given to getting a prototype to Haiti. The SHSU group claims their "revolutionary" scheme easily scales up to larger installations.

* POPULAR SCIENCE had a note on "Mobile Digital TV (MDTV)", a new digital TV broadcast service now operating in 17 major US cities. Previously, the only way to get video on a mobile wireless device was via download, which could be expensive, but MDTV is a free service, supported by advertising just like regular broadcast. MDTV does of course require that devices have an MDTV receiver chip; MDTV-enabled devices are expected to be available later in 2010, with USB plug-in modules available for laptops and the like.

[ED: As of 2022, MDTV is almost invisible, but apparently there are MDTV stations in big cities.]

* BBC.com had an audio slideshow on a project to refurbish New York City's famous Empire State Building to improve its energy efficiency. The upgrade, which is to cost about $550 million USD, involves replacing all 6,500 windows in the building with insulating windows, and temporarily yanking all the radiators to permit installation of an insulating barrier that will block heat transfer through the walls. One of the big factors in the exercise was that about a third of the building currently isn't air-conditioned, which makes finding tenants more difficult. The plan was to air condition all the public spaces in the structure, with the first thought being to replace the chiller plant. Then somebody suggested "work smart not hard" -- and first determine how energy efficiency planning going on in parallel affected the air conditioning issue. As it turned out, the energy efficiency updates would be enough to permit full air conditioning without replacing the chiller plant. That saved $17 million USD that would have been required to replace the plant, if at the expense of pumping more money into energy efficiency. On the balance, it was a bargain.

* In really off-the-wall gimmick news, DISCOVERY.com reported on a passive near-field communications (NFC) data module named "RosettaStone" from a company named Objecs. NFC is used in RFID systems; the RFID module doesn't require power, the power being obtained from an electromagnetic field generated by the reader device.

The RosettaStone is intended to be embedded in a tombstone; presuming a visitor has an NFC-enabled cellphone, it can be then used to obtain a file of information on the, uh, "occupant". On first sight this seems like a completely ridiculous idea, but then again we're reaching the era of "internet of things" in which any conceivable product will have a digital ID tag, in which refrigerators will be able to query milk cartons to see if they're past their expiration date. Okay, so why wouldn't tombstones be part of the atomized internet as well?

Of course there's a long list of practical issues to be considered, for example how long a RosettaStone could be expected to last when exposed to the elements outdoors and, maybe more importantly, if NFC schemes in use now will have any compatibility with the communications tech of the future. Still, it sounds considerably more practical a way to leave a personal memento for the future than having one's head frozen -- though that's admittedly a very low standard of comparison.

COMMENT ON ARTICLE* NOT SO SILENT MUTATIONS: The proteins that help construct our body consist of chains of molecular "building blocks" known as "amino acids", with the pattern of the chains defined by the DNA sequences in our genes. DNA is structured around a set of four molecular building blocks of its own, known as "bases", with "triplets" of bases defining specific the amino acids in a protein chain. There are 20 different amino acids and 4 x 4 x 4 = 64 possible DNA triplets to specify the amino acids; there are generally multiple triplets to specify a particular amino acid.

As discussed in an article in SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN ("The Price Of Silent Mutations" by J.V. Chamary & Laurence D. Hurst, June 2009), it was long thought that any genetic mutation that modified a specific DNA triplet in such a way that it coded for the same amino acid before and after the mutation made no change in an organism, and so such "synonymous mutations" were often equivalently called "silent mutations". However, in the 1980s evidence began to accumulate that synonymous mutations weren't necessarily silent.

The first clue that "broke the silence" was statistical. If it didn't matter which of several triplets coded for the same amino acid, then by the simple odds of the matter, all the different triplets that coded for the same amino acid would be roughly as common. In bacteria and yeasts, that didn't turn out to be the case, with some triplets being much more common than others. Investigation showed that though two triplets might code for the same amino acid, the cellular machinery used to synthesize proteins might well work much more efficiently with one triplet than with another.

The difference in efficiency was traceable to an issue of supply. The DNA molecule, as is well known, consists of a "double helix", with two matching chains linked together like a long twisted ladder. The cellular machinery that produces proteins first splits the double chain down the rungs of the "ladder" to produce a half-chain, and then uses one of the half-chains as a template to produce a half-chain of a similar molecule known as "messenger RNA (mRNA)". The mRNA is fed to a cellular organelle known as a "ribosome" that reads the "memory tape" provided by the half-chain of mRNA to assemble the protein, being fed amino acids by triplet chunks of RNA linked to their corresponding amino acids, known as "transfer RNA (tRNA)". As it turns out, a bacterial or yeast cell may contain far fewer tRNAs for one triplet than it does for a second, meaning that protein assembly is much more troublesome for the first triplet than it is for the second. For this reason, proteins that the cell synthesizes in large quantity have genetic codes with a greater bias towards one triplet than those that are synthesized in small quantity.

Later studies for other organisms, such as plants, flies, and worms, revealed that many have similar biases in triplet codings. Mammals feature biases in triplet codings as well, but they don't follow the same pattern: the mammalian genome is roughly organized in blocks, and the biases tend to differ between blocks. Even now, nobody's quite sure what that means, but in any case the general assumption was that, as far as mammals were concerned, synonymous mutations were irrelevant -- truly silent.

Then, in the early 2000s, analysis of the rates of evolutionary change in the genomes of mammals suggested this assumption was wrong. Evolutionary selection pressures tend to "fine tune" the genomes of organisms to make them better adapted to their environment, with "bad" mutations tending to die out while "good" mutations are retrained. If synonymous mutations were truly silent, neither "bad" nor "good", they would be indiscriminately retained -- but the studies showed that they weren't, selection pressures did have an effect on which triplets were retained. That meant the synonymous mutations did have effects.

It required some effort to figure out exactly what. Our genes do not necessarily run continuously on our genome; they may include "noncoding" segments called "introns" that our cellular machinery has to toss out to splice the coding sections of the gene, the "exons", together for producing a protein. Some DNA triplets lead to higher error rates in splicing than other triplets that code for the same amino acid. Dozens of genetic disorders have now been traced, in part or in some cases in all, to synonymous mutations that were once believed to be silent -- for example, synonymous mutations appear to contribute to cystic fibrosis.

Even disregarding the splicing issue, synonymous mutations can make a difference in the folding of a protein. The effectiveness of a protein is not just due to the sequence of amino acids in the protein chain, but also to the way the three-dimensional structure it folds up into. Synonymous mutations can cause a delay in the folding of a protein as it is synthesized, resulting in a misfolded protein that can have disastrous consequences for the organism.

Scientists see the understanding of the possible effects of synchronous mutations as both providing tools to enhance commercial production of proteins by genetic engineering techniques, allowing optimizations of protein production rates; and to obtaining a better handle on genetic disorders. Much more research remains to be done, much more needs to be learned.

COMMENT ON ARTICLE* METAMATERIALS, THE NEXT GENERATION: Back in 2001, researchers in the US and the UK pulled off a trick that many had assumed impossible: they managed to bend light backwards, developing a "material" with a negative refractive index. The experiment involved shining microwaves -- not precisely light, but the same as light with much longer wavelengths -- at a circuit board topped with an array of rings and wires that represented the "material". It was a funny sort of "material", more like a contraption, but it set physicists to rethinking what they knew about light and optical technology.

As reported by an article from AAAS SCIENCE ("Next Wave Of Metamaterials Hopes To Fuel The Revolution" by Robert F. Service, 8 January 2010), almost a decade later, researchers have made major strides in "metamaterials", as the technology was named, pursuing ideas to create invisibility shields, ultrasharp focusing, and materials that could mimic the ability of black holes to absorb light. Unfortunately, while physicists have been demonstrating ever more clever optical tricks in the lab, they're uncomfortably aware that they haven't been able to come up with anything but laboratory toys. It's predictable that applications will lag major scientific breakthroughs, but those working on metamaterials feel that they really need to show they're actually good for something.

* Traditional optical technology uses mirrors and lenses to focus light. Lenses perform their focusing thanks to their curvature and the "refractive index" of the glass they are made from. The refractive index is the relation of the speed of light in different materials to its speed in a vacuum; for example, the index change between air and water is what causes a straw in a glass to appear "bent" under the surface of the liquid in the glass.

In conventional optics, the index of refraction is always a positive value. In the 1960s, a Soviet theoretical physicist named Viktor Veselago suggested that it might be possible to engineer structures that had a negative index of refraction. If water had a negative index of refraction, the straw would not seem bent under the surface of the liquid in a glass, it would instead seem to stick back out of the water. Veselago's work suggested that there might be an entire domain of structures that had radically new optical properties.

Veselago's idea, crazy as it sounded, was taken seriously, but it wasn't until 2001 that two researchers -- John Pendry of Imperial College London and David Smith, now at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina -- actually demonstrated a structure with a negative index of refraction. They fabricated an array of metal wires and rings, with a thin slice cut out of the rings, and then shined microwaves onto the array. The microwaves excited electrons in the rings, causing them to slosh back and forth and produce a resonant electromagnetic field to induce a negative index of refraction into the beam.

Since that time, physicists and materials researchers have performed more sophisticated experiments in metamaterials -- but only in the microwave and other parts of the electromagnetic spectrum below the infrared. The problem is that the components of a metamaterials array must have dimensions smaller than those of the wavelength of the electromagnetic radiation they affect. That's not a problem with microwaves, since they have wavelengths in the centimeters, but it is a problem with infrared or visible light, which have wavelengths in the micrometer and nanometer range. Even with modern microchip fabrication technology, it is difficult to fabricate metamaterials arrays at such dimensions.

To make matters worse, metamaterials researchers like to use metal in their work. Metals work fine for microwaves, but are strong absorbers of infrared and visible light. Researchers have tried to dodge this problem by using metal thin films to reduce the absorption, but such thin films are very limited in the effects they can produce.

* To get around the obstacles against working in the infrared and visible regions of the spectrum, researchers have turned to precisely patterned geometrical 3D structures. A team at the University of Karlsruhe in Germany, for example, has used precision laser cutting to carve an array of helical channels turned either clockwise or counterclockwise into a block of polymer. The polymer is then used as a mold, with the channels filled with gold and the polymer removed to a reveal an exquisite array of golden spirals. When exposed to infrared light, the array acts as a polarization filter -- something that can of course be done with conventional optics, but the gold metamaterials array works over a much wider range of frequencies.

A group at the University of California at Berkeley has also built a metamaterials array with a negative index of refraction in the infrared. The array is built from alternating layers of magnesium fluoride and silver, with a precision ion beam used to carve holes into the stack, leaving behind a fishnet pattern. The pattern results in circuits between the alternating layers, with electron movement in the layers setting up a resonant electromagnetic field that produces negative refraction of infrared light shined onto the array. The Berkeley researchers have more recently reported operating a new array that works on similar principles, but built in the form of silver nanowires grown inside a sheet of porous aluminum oxide.

Unfortunately, schemes along such lines only work for light within a narrow spectral range, or shined from very specific directions. Researchers from the US Sandia National Laboratories in Albuquerque, New Mexico, have been working on a new approach that promises to work with infrared coming from any direction. They are depositing metal through a membrane onto a curved polymer surface, with the curved configuration providing structures that work effectively regardless of the orientation of the infrared light beam. The Sandia researchers haven't actually built a full metamaterials array yet, but feel they are making good progress towards one.

Other research groups have tackled the absorption problem by adding nanoparticles or other materials that produce light when illuminated to metamaterials arrays, with the light production compensating for the absorption. So far, researchers haven't had much luck with this approach, but they aren't discouraged. Metamaterials is a new world of physics and researchers have only scratched the surface, with a wide range of possible techniques available for further investigation. Says one: "It's a pretty rich tool set. People are still exploring what you can do."

COMMENT ON ARTICLE* ENEMY RECOGNITION (1): Our immune system has a powerful capability to recognize dangerous pathogens and work to destroy them. As reported by an article from AAAS SCIENCE ("Internal Affairs" by Mitch Leslie, 13 November 2009), we are still learning more about the molecular mechanisms by which our cells recognize and deal with invaders. While we have become increasingly familiar with the cell's external defenses, we are now finding out that the cytoplasma that fills the interior of the cell includes defenses as well. A better understanding of these cytoplasmic defenses may lead to improved vaccines against pathogens that have so far been evasive targets, as well as treatments for conditions such as gout that seem to be linked to an immune response gone wrong.

* Many animal cells, particularly sentinels of the immune system such as macrophages and dendritic cells, inspect their surroundings with extracellular structures called "Toll-like receptors (TLRs)", more than a dozen of which have been identified to date. Each different TLR can recognize a particular constant ("conserved") feature of certain broad classes of pathogens, with such features referred to as "pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs)". For example, the Toll-like receptor TLR-5 recognizes a protein named "flagellin", which is a component of the whiplike flagellum that propels many species of bacteria. Once sentinel cells recognize an invader from its PAMPs, the sentinels lead the charge of the immune system against it. The immune system first attacks with a general "innate" immune response and then, using B cells and T cells, an "adaptive" immune response that precisely targets the invader.

Work on plant cells showed that the cytoplasm of such cells contained equivalents of TLRs known as "resistance" or "R" proteins. The immune system of plants is extremely different from that of animals, but the discovery of R proteins made researchers curious about whether we had comparable cytoplasmic defenses. About a decade ago, researchers began to search through mammalian genomic databases to see if they could find analogues of these proteins. They struck gold.

According to immunologist Brad Cookson of the University of Washington (UW) in Seattle, "there's an elaborate intracellular detection array, just like there's an elaborate extracellular array." So far, about 20 intracellular pathogen sensors known as "nucleotide-binding domain & leucine-rich repeat-containing proteins" -- thankfully abbreviated as "NLRs" -- have been found, with the NLRs capable of identifying features of bacteria, parasites, and other intruders. The NLRs aren't alone, either, with other cytoplasmic detectors including:

* Having identified the detectors, the next question for researchers is to determine exactly what they detect, and some progress has been made on the matter. Like TLRs, some of the intracellular detectors bind to PAMPs. RIG-I, for example, zeroes in on viral RNA molecules, allowing it to target killers such as HIV and the hepatitis C virus. Recent research shows that the cell is adapted to assist RIG-I and help it target a wider range of intruders. The cell uses the enzyme "RNA polymerase" to convert a DNA strand into a messenger RNA strand that is then used to synthesize proteins -- but RNA polymerase floating around in the cellular cytoplasm will also convert any stray DNA it finds into double-stranded RNA. Since the cell's own DNA complement is concentrated in the nucleus and in mitochondria, the odds are that stray DNA is from a pathogen. Converting such stray strands into double-stranded RNA allows them to be detected by RIG-I, extending its target range to DNA-based viruses, such as adenoviruses and Epstein-Barr viruses, and even some bacteria.

However, for the most part the action of these intracellular detectors remains mysterious. For example, the intracellular protein NLRP3 not only detects bits of bacterial cell walls in the cytoplasma, but also toxic industrial substances like asbestos and silica, as well as the monosodium urate crystals that torture gout sufferers. The problem is that nobody has been able to figure out how NLRP3 actually does any of this. There's a suspicion that we're only seeing part of the system, that there is an unknown set of intracellular detectors that actually bind to the targets, with the NLRs simply serving as intermediaries. Another idea is that the NLRs do not recognize the intruders as such; they actually recognize the damage the intruders cause in the cell. [TO BE CONTINUED]

NEXT | COMMENT ON ARTICLE* THE KILLING OF JFK -- LEE HARVEY OSWALD (6): Although Oswald didn't hit it off well with most of the Russian emigres he met in Fort Worth, he did strike up an unlikely friendship with one of them, George de Mohrenschildt. De Mohrenschildt was an oil geologist, wealthy, well-educated, well-traveled, from an aristocratic family of the days of the tsar. He had been friendly with the high-society Bouvier family some years back and had known the current First Lady, Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, as a child. Some conspiracy theorists have suggested that there was something sinister about de Mohrenschildt's association with Oswald. Why would somebody like him care about such a loser? Conspiracy theorists also point to the fact that de Mohrenschildt had "CIA contacts".

He did have contacts with the CIA, but there was less to that than meets the eye, and it's well worth discussing in some detail because the matter comes up again. Intelligence services don't get all their information from under the table: they scan through perfectly ordinary sources such as newspapers, books, almanacs, maps, and so on, to help build up a picture of a target country. As part of its "open source intelligence" effort, the CIA had a "Domestic Contact Division (DCD)" -- sometimes also known as the "Domestic Contact Service (DCS)" -- that would interview or get reports from ordinary Americans who had traveled abroad, particularly to East Bloc countries. The DCD talked to tens of thousands of Americans traveling abroad each year. The people interviewed were not on the CIA payroll and the CIA did nothing but ask them some questions. How much value the DCD had in intelligence-gathering might be debated; there is no doubt, however, that it proved a goldmine for conspiracy theorists, providing them with very long lists of "CIA contacts", who could easily be portrayed as "covert CIA agents'.

De Mohrenschildt did a lot of traveling and ended up talking with the DCD, ensuring that he would be eventually smeared with the "CIA agent" brush. Some have also suggested that de Mohrenschildt had been working for the Nazis during World War II, while others claimed he had KGB contacts. De Mohrenschildt said he had actually worked for French intelligence during the war, and there is no evidence to link him to the KGB -- for what it's worth, after the fall of the USSR, the KGB said they'd never had a file on him.

Anyway, so why did a classy guy like de Mohrenschildt take an interest in Oswald? It was not as unlikely as it looked. Those who knew de Mohrenschildt found he had an obnoxiously contrary streak, for example going to black-tie parties in a swimsuit; he would provoke Leftists by praising Fascism, provoke Rightists by praising Communism, and people generally regarded him as a "bullshitter". His background might have been aristocratic, but like Oswald he had what would later be called an "attitude" and his behavior was erratic; his flashy wife Jeanne was at least as out-of-control as her husband. De Mohrenschildt had plenty in common with Oswald.

* Oswald was sick of his job at Leslie Welding Company and simply stopped showing up for work on 9 October. On being told that employment prospects were better in neighboring Dallas than they were in Fort Worth, he started job-hunting there. In October 1962 the Texas Employment Commission managed to place him with Jaggars-Chiles-Stovall Company, a graphics-arts firm, working in photoprinting. Conspiracy theorists have made much of this: while the company mostly put together ads for print media, it also had a contract with the Army Map Service, and so the claim was made that Oswald had "extensive access to classified materials". In reality, only a small part of the company's work was classified, and that part was only handled by employees with a government security clearance. Oswald didn't have a security clearance, and given his past history there was no way he was ever going to get one, either.

Conspiracy theorists have pointed out that Oswald wrote "microdots" next to the entry for Jaggars in his address book. In reality, at the time he was incorporating "playing spy" into his already elaborate fantasy world. He liked tinkering with the company's equipment and worked after hours on forging official documents, for example producing a crude facsimile of a Marine Corps Certificate of Service under the name of "Alik Hidell" -- an alias he cooked up from his nickname while in the USSR, "Alek", and a Marine named Heindel who he'd known in the service. Oswald liked this alias and would keep on using it or variations of it.

Oswald moved his family to a dingy apartment in Dallas at the beginning of November. The move led to particular tensions between husband and wife, with Marina beaten repeatedly. The move generally broke the family's contacts with the emigre community, though he did still see de Mohrenschildt on occasion. The family had Thanksgiving dinner at Robert Oswald's house; in the interests of harmony, Robert made a point of not inviting Marguerite. John Pic was there, the first time Lee and John had met in ten years. It was also the last. [TO BE CONTINUED]

START | PREV | NEXT | COMMENT ON ARTICLE* Space launches for February included:

-- 02 FEB 10 / PROGRESS 36P (ISS) -- A Soyuz booster was launched from Baikonur to put a Progress tanker-freighter spacecraft into orbit on an International Space Station (ISS) supply mission.

-- 09 FEB 10 / ENDEAVOUR (STS-130) / ISS -- The NASA space shuttle Endeavour was launched from Kennedy Space Center on "STS-130", an International Space Station (ISS) support mission. This was the 130th shuttle flight and the 24th flight of Endeavour. It was the last scheduled shuttle night launch. There were six crew, including:

Endeavour carried the "Tranquility" connecting node and the "Cupola" observation deck module for the ISS. The shuttle docked with the ISS on 10 February, with the shuttle crew joining the ISS "Expedition 22" crew of commander Jeff Williams and engineer Oleg Kotov. The shuttle returned to Earth on 22 February, landing at Kennedy Space Center after 13 days 8 hours 8 minutes in space.

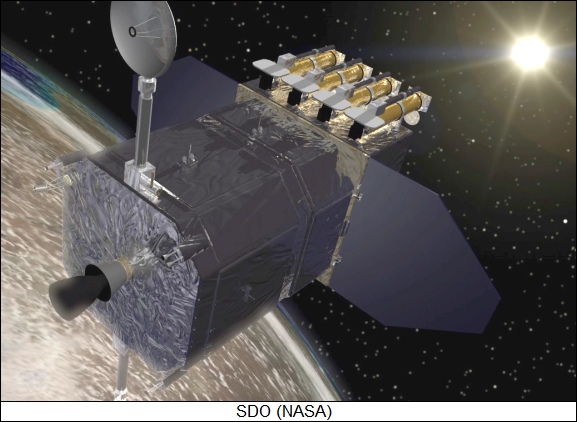

-- 11 FEB 10 / SOLAR DYNAMICS OBSERVATORY -- An Atlas 5 401 booster was launched from Cape Canaveral to put the NASA "Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO)" into geostationary orbit. SDO had a launch mass of 3,200 kilograms (7,000 pounds) and carried a payload suite based on three elements:

The instruments returned data at a rate of 150 megabits per second, requiring use of a Ka-band downlink and dedicated receiver systems on the ground. The mission was planned to last five years, but the spacecraft had enough consumables for ten years of operations. SDO was the first mission in the "Living With A Star" program to analyze the Sun, with an eye on solar influence over the Earth's environment and human technological systems. The Atlas 401 launcher had a 4-meter (13-foot) payload fairing, no solid rocket boosters, and an upper stage with one Centaur engine.

-- 12 FEB 10 / INTELSAT 16 -- A Proton Breeze M booster was launched from Baikonur to put the "Intelsat 16" geostationary comsat into orbit. The spacecraft was built by Orbital Sciences, carried a payload of 24 Ku-band transponders, and had a design life of 15 years. It was placed in the geostationary slot at 58 degrees West longitude for direct-to-home services to Latin America, being operated by Intelsat on behalf of SKY Mexico and SKY Brazil, local subsidiaries of DirecTV of the US.

* OTHER SPACE NEWS: The Iranians recently put on display a mockup of their new "Simorgh (Phoenix)" two-stage liquid-fueled satellite launch vehicle. It is 27 meters (88 feet 6 inches) long; has four engines on the first stage and one on the second stage; and can put a 60-kilogram (132-pound) payload into orbit. The Iranians also displayed information on a new small telecommunications satellite, a reconnaissance satellite, and a satellite that was presented but not described.

There were concerns that the Simorgh represented Iranian progress in development of long-range missiles, but Pentagon intelligence reports have downplayed Iranian progress in the missile field. Conservative assessments of Iranian missile capabilities led the Obama Administration to cancel deployment of heavy antimissile interceptors to Poland, much to the joy of the Kremlin and disgust of American conservatives. However, the Obama Administration was simply stepping back to a less ambitious plan, and is now pushing for deployment of smaller SM-3 interceptors in Romania. The Russians are once more annoyed.

* AVIATION WEEK reports that Globalstar, owner of the Globalstar satellite world-wide mobile communications system, is planning to launch an initial set of six second-generation replacement satellites in the coming summer, with a total of 24 satellites in place by the middle of 2011. The new satellites will replace half the 48 satellites of the original constellation, which has been in operation since the late 1990s. Ground system improvements are being implemented in parallel. While the new satellites support channel speeds of 256 kilobits per second (KBPS), up from 9.6 KBPS of the current system, the higher data rates won't be available until the ground system is up to speed in 2012.

The first-generation network provided circuit-switched voice and data connections, but the second-generation satellites will supply packet-switched Internet Protocol-based voice, messaging, video, and other communications services at higher data rates. The second-generation spacecraft are being built by Thales Alenia Space of Italy and will be shipped to Baikonur in Kazakhstan for launch on a Soyuz booster.

COMMENT ON ARTICLE* CONNECTOMICS: As discussed in an article in THE ECONOMIST ("Wired", 8 April 2009), the 2008 Nobel Prize in chemistry was awarded to three researchers -- Osamu Shimomura, Martin Chalfie, and Roger Tsien -- for discovering "green fluorescent protein (GFP)" in jellyfish and determining how it could be used to trace the biological functions of various other organisms. A neurobiologist named Jeff Lichtman has followed up on this discovery to develop a way to tag the nerve cells of mice with genes that produce proteins fluorescent in red, green, and blue. Using the full color imagery provided by the "brainbow" proteins, Lichtman was able to obtain insights into the elaborate wiring of the mouse brain. He intends to use the brainbow mice to investigate neurological development, which besides being interesting in itself could help deal with the occasions when brain wiring doesn't develop as it should, resulting in the afflictions lumped as "connectopathies".

Lichtman's work is one of the most famous examples of the emerging science of "connectomics". Just as every organism has a "genome", a set of genetic codes to define its architecture and operation, they also have a "connectome", a network of nerve cells with a particular pattern of connections, though unlike the genome the connectome alters over time as new connections are formed and older ones break. Lichtman and others in the field dream of a "Human Connectome Project", analogous to the Human Genome Project, to unravel the map of the human connectome.

The science of connectomics actually began well before the word itself existed. In 1972 Sydney Brenner, a biologist then at Cambridge University in the UK, decided to unravel the nervous system of a small roundworm named Caenorhabitis elegans. The roundworm seemed like an excellent subject for such an investigation, since it only has about a thousand cells overall, with about 300 of them neurons. It is also hermaphroditic, capable of breeding itself, producing generations of generally identical roundworms, and it is easy to breed them in large numbers. Brenner's research team embedded the roundworms in blocks of plastic, then sliced the blocks into thin sheets and stained them to permit detailed examination under an electron microscope. After fourteen years of exhausting study, the research team was able to produce a complete map of the nervous system of C. elegans. For this and other work, Brenner shared the 2002 Nobel Prize for medicine.

Such an approach is flatly not practical for mapping the connections of, say, the brain of a mouse. The cerebral cortex -- the part of the brain that "thinks" -- is made up of two-millimeter-long elements known as "cortical columns"; Winfried Denk of the Max Planck Institute for Medical Science in Heidelberg estimates that to map out one cortical column would take a graduate researcher, using Brenner's methods, about 130,000 years. Call it job security.

Of course, automation has come a long ways from the 1970s and 1980s, and machines can now do much of the grunt work far faster and more cheaply than a grad student. Brenner's group, for example, used a transmission electron microscope (TEM), in which the electron beam passes through the sample to be picked up by the imaging sensor. The problem is that a TEM has to work one carefully-prepared slide at a time. In contrast, a scanning electron microscope (SEM) images the reflection of an electron beam off a sample. Denk's group uses a SEM with an automated slicing mechanism; instead of imaging a slide at a time as with a TEM, a researcher can feed the SEM an entire block, with the SEM scanning the surface, then slicing off the top layer to image the next layer.

Researchers have also figured out clever ways to tag particularly interesting parts of the brains. A single neuron has dendritic tendrils that branch wildly through a brain; Denk's research team uses an enzyme, derived from horseradish of all things, that coats the surface of a selected neuron and then reacts visibly to a stain. Ed Callaway of the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California, has even made use of the rabies virus, a notorious assailant of the nervous system, with the virus jumping from neuron to neuron to trace nerve connections.

Brenner's team also had to make do with the "Mark One Eyeball" to determine the patterns in the roundworm nervous system, but in the 21st century image analysis software is well developed and in widespread use. Sebastian Seung, a computational neuroscientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, is writing a program to sift through the sets of data and build up a map of neural connections by trial and error.

The mouse is the primary target for current work in connectomics, since it is cheap, breeds fast, and its brain is relatively simple -- half a gram in mass, with only 16 million neurons. Compared to the roundworm nervous system, the mouse brain still remains an ambitious target, four orders of magnitude bigger. Once the mouse brain is mapped, the tools should be in place to take on the next target, the human brain, which weighs 1.4 kilograms and contains an average of 86 billion neurons. That may seem like an intimidating goal, but the potential rewards are great enough to make it worthwhile. [ED: The text originally said "100 billion neurons", but refined studies reduced the count somewhat.]

COMMENT ON ARTICLE* RIDE THE DIGITAL CAR: As reported by an article from IEEE SPECTRUM ("This Car Runs On Code" by Robert N. Charette, February 2009), the new Lockheed Martin F-35 Joint Strike Fighter features about 5.7 million lines of program code to run its systems, while the new Boeing 787 Dreamliner has about 6.5 million lines of code. Sounds impressive? Then consider that a luxury auto with deluxe bells and whistles runs on 100 million lines of code, executing on 70 to 100 microprocessor-based "electronic control units (ECUs)" distributed around the car.

The radio and navigation system alone of the current S-Class Mercedes Benz runs to 20 million lines of code, and the car has about as many ECUs as an Airbus A380 super-jumbo jetliner -- excluding the jetliner's in-flight entertainment system. Even low-end cars now have 30 to 50 ECUs. ECUs are found in subsystems for airbags, antilock brakes, engine ignition and control, windshield-wiper control, automatic transmission, climate control, power steering, and of course entertainment / communications systems. In a few years, it is likely that the amount of code in a car will double or even triple.

One of the drivers for the explosion of code in a car is the need to save energy, reduce emissions, and improve safety by making the car "smarter". For example, a car's airbag system has to reliably operate for years in a range of environmental conditions, from very cold to very hot, without deploying airbags on a false alarm -- and then deploy them, in a sequence appropriate to the impact direction, in a fraction of a second when they're needed. Now work is in progress to allow the airbag system to inform emergency responders just how severe the crash was.

The first automotive ECU was a single-function controller used for electronic ignition timing in the 1977 General Motors (GM) Tornado. The next year, 1978, GM offered as an option a "Cadillac Trip Computer" based on a Motorola 6802 processor for the Cadillac Seville that provided data on fuel use, speed, and engine information. By 1981, GM cars had about 50,000 lines of code, and other car manufacturers were getting on the digital bandwagon.

At the time GM began to put advanced electronics into its cars, electronics was about 5% of the cost of a car's hardware; now it's over 15% on average, and up to 45% for hybrids, with their more complicated propulsion scheme. Some believe that the electronics is likely to easily run to half the cost of car hardware in the not-too-distant future. Even at present, software development contributes up to 15% of the sticker price of a car.

This greater complexity is absolutely not without its drawbacks, with major manufacturers forced to perform expensive recalls to fix software problems. Even though a good portion of a car's firmware is devoted to diagnostics, it's still hard to fix such a complicated system, and industry stats show that half the ECUs that mechanics swap out actually work perfectly well. Automotive designers have hopes that remote diagnostics -- ultimately performed by a car over wireless at home in the garage -- may help deal with the growing maintenance problem.

Others may be very skeptical of that idea, but like it or not, cars are going to keep on getting more complicated as sensor systems are incorporated to keep an eye on traffic and obstacles, and wireless systems are added to link into traffic control systems. The ultimate goal is a car that drives itself -- which most will agree is an interesting idea in principle, but drivers are going to need a lot of convincing before they'll be willing to give up the wheel to a car running on hundreds of millions of lines of code with a statistically known fraction of defects.

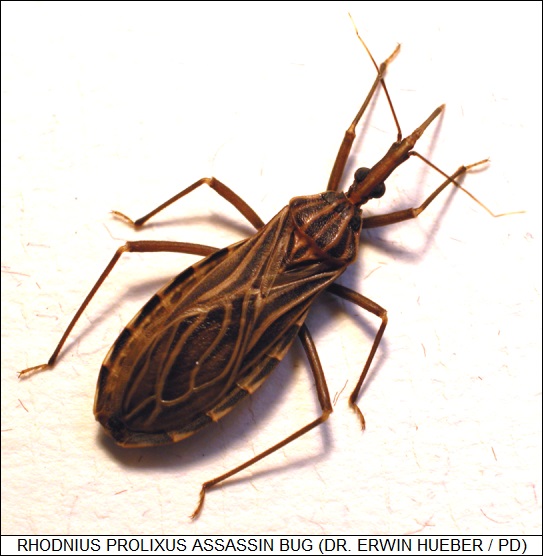

COMMENT ON ARTICLE* PARASITIC WASP GENOME (2): The vast numbers of parasitic wasp species seems to be linked to the fact that 90% of known wasp species are "picky eaters", targeting only one or two host species. That implies a lot of wasp species. As Warren points out, while caterpillars are seen as the stereotypical target of the wasps, they're hardly restricted to them: "Virtually every arthropod on Earth is attacked by one or more of these parasitoid wasps."

The target selectivity of parasitic wasps makes them potentially useful for pest control. Cassava is a leafy edible plant that is a staple in many African countries, having been imported from South America 400 years ago. In the 1970s, the cassava mealybug, which lives on cassava, followed the plant to Africa from South America; by the 1980s, the mealybug was laying waste to cassava fields. However, the mealybug was not all that common in South America. Something was keeping it in check, and investigation showed it was the parasitic wasp Apoanagyrus topezi. After testing the wasp to ensure that it wouldn't become a pest itself, it was released in African countries where the mealybug was a problem. The mealybug was all but wiped out.

The idea of using a precisely targeted wasp species as a "magic bullet" to selectively kill off pests is a tempting one, but it's not as easy as it sounds. The cabbage butterfly was introduced into the USA late in the 19th century and quickly made a nuisance of itself. A parasitic wasp that targeted the butterfly was imported from England in 1881, but it wasn't suited to the climate where the introduced butterfly ranged, and proved ineffectual. Another wasp imported from Yugoslavia in the 1970s proved no better. Finally, a wasp was imported from China in the 1980s that was better suited to the climate, and has proven highly effective in killing off the butterflies. However, private companies have never been particularly interested in using parasitic wasps for pest control because, once the wasps have been introduced, they're self-supporting and so there's no more sales to be made. Governmental and non-governmental agencies have also become more reluctant to take chances on the unpredictable results of introducing foreign species. In short, it's not something people are inclined to do if they don't absolutely have to.

* In contrast, enthusiasm for the parasitic wasp as a lab animal has been increasing. One species of wasp has been a particular favorite, the fly hunter Nasonia vitripennis. It's easy to raise in the lab, has a short life-cycle, and can be interbred with closely related species -- if treated with antibiotics first, since species-specific Wolbachia bacteria will otherwise render the couplings sterile.

The prominence of N. vitrepennis made it a high-priority target for genomic analysis, and the sequencing of its genome, as well as of two close relatives in the Nasonia genus, attracted a good deal of attention. John Werren pushed the project in collaboration with Stephen Richards of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, with Werren pointing out the unique benefits of a hymenopteran for genetic studies. We are "haploid" animals, with two sets of chromosomes in our cells, while the hymenoptera are "haploduploid": the females have two sets of chromosomes, while the males hatch from unfertilized eggs and only have a single set. That means that genetic changes will show up immediately in male hymenopterans, since they don't have parallel second genes that could mask mutant genes. Interestingly, the wasp genome has 450 genes in common with humans not found in the Drosophila fruitfly, long the standard insect for lab studies, meaning the wasp may prove to be a closer genetic analogue to humans than the fruitfly.

* Of course, the Nasonia wasps are also interesting targets of genetic study because of their specific adaptations. N. vitripennis parasitizes larvae of house flies and other "filth flies", and is not too picky about its hosts. However, its sibling species only target blowflies found in bird nests. Work is underway to nail down the wasp genes responsible for host preference, a task that not only promises to reveal new insights into the emergence of species or "speciation", but hints that some day we might be able to genetically engineer parasitic wasps to attack any arthropod pests we want to control.

Another interesting feature of parasitic wasps is that they produce venoms that have a wide range of effects on target hosts, with these venoms having potential applications in biomedicine. Researchers have performed a computer analysis using the new Nasonia genome and mass spectroscopy analysis of the wasp's venom to identify 79 proteins in the genome -- half of which had not been recognized as venoms before, with about a quarter of the total being unlike any seen before.

Wasp venoms appear to evolve very rapidly, with specific venom cocktails often more effective against one host than another. The adaptation of venoms appears to be one of the processes driving the massive diversification of parasitic wasp species. Another process driving the speciation of the wasps appears to be the high mutation rate of their mitochondrial DNA. The cells of "eukaryotic" organisms -- as compared to the "prokaryotes", the bacteria and their sibling group the archaea -- have DNA in the cell nucleus and separate DNA in the cellular organelles known as "mitochondria". It is known that mitochondrial DNA tends to mutate faster than nuclear DNA, with the rate of mutation of mitochondrial DNA in Drosophila running about seven times faster than the nuclear DNA. In wasps, the rate is about 35 times faster. The mitochondrial and nuclear DNA functionally complement each other, and the high mutation rate means that the mitochondria of one strain of wasps quickly become incompatible with the cells of another strain of wasps.

As ghastly as parasitic wasps are, researchers have come to appreciate what they have to offer. As Claude Despan, a geneticist at New York University in New York City, says of Nasonia: "This species is no longer a 'weird' species with interesting features. It has graduated to be of help to address questions that cannot be that easily investigated in flies." [END OF SERIES]

PREV | COMMENT ON ARTICLE* THE KILLING OF JFK -- LEE HARVEY OSWALD (5): Conspiracy theorists have wondered why Lee Harvey Oswald was not harassed by American authorities when he came back from the USSR, but the truth was that his temporary stay in the Soviet Union did not break any US laws. He could not have betrayed any secret information to the Reds for the simple reason that he possessed no secret information to betray. Of course, he was now automatically disqualified from ever obtaining even the most casual security clearance -- but since he wasn't in any position to obtain a job that required a security clearance, or for that matter any job that required more than menial skills, that wasn't an issue either.

American authorities did have some interest in him, which of course conspiracy theorists also try to make out as suspicious. Not long after Oswald had arrived in Fort Worth, the FBI gave him a call; the bureau had opened up a file on him when he went to the USSR and wanted to talk to him. The interview, with Agent John Fain, was on 26 June 1962 and it was confrontational, with Fain finding him evasive and uncooperative. Later Lee told Robert that the FBI had asked him if he was a US government agent; he laughed at them and replied: "Well, don't you know?!"

In July, Marguerite Oswald showed up in Fort Worth, rented a tiny apartment, and asked that Lee move in with his family. Lee didn't like the idea but Marguerite was as always inflexible, and they moved in on 14 July. He got a job as a sheet-metal worker with Leslie Welding Company three days later. Marguerite got to picking on Marina, with the tension escalating until Lee took his family out of the apartment on 10 August, with Marguerite throwing a screaming fit, running after the car when Robert Oswald took them away.

Lee took his family to a broken-down rental house. On 16 August, the FBI dropped by; they wanted to talk to him again. Agent Fain was still not satisfied with the evasive answers Oswald gave him, but when he asked Oswald if the Soviets had asked him, Oswald, to do them any favors, Oswald replied: "No. I was not that important." Fain saw the truth in this and, despite his continuing distrust, decided to close Oswald's file. It could be opened again when needed, but for now Oswald had disappeared off the FBI's screens. Some conspiracy theorists insist that the FBI visited Oswald in order to recruit him, but given his residence in the USSR, the bureau had legitimate reason to check up on him and there's no evidence that the FBI did any more than question him. Ironically, even though the FBI had filed him away for the time being, Oswald would see the bureau's malign hand in his personal troubles from then on.

Oswald was frustrated. He and Marina were not getting along well, leading to quarrels and occasional sessions of wife beatings. He was involved with a group of Russian emigres through Marina; the emigres found him erratic, "not quite right in the head". Oswald remained a noisy Communist -- although he didn't have a high opinion of the USSR, he shrugged it off as a bad implementation of a good idea -- which didn't go over well with the emigres either, since most were anti-Communist. Oswald remained in character in his ability to win friends and influence people. [TO BE CONTINUED]

START | PREV | NEXT | COMMENT ON ARTICLE* SCIENCE NOTES: It is known that the human genome includes some sequences that were obtained from "retroviruses" -- the class of viruses, the best-known member being the HIV pathogen that causes AIDS, that have a genome made of the RNA molecule instead of the DNA molecule, and insert their genome into a host cell genome. At some occasions in the past, retroviruses inserted their genomes into the human germ cell line and left their markers with us. Fortunately, the genomes of all such retroviral hitchhikers in our genome are broken by mutations, so they can't be expressed and produced.

Somewhat to their surprise, a team of Japanese researchers found copies of the genome of a "bornavirus", a virus that causes diseases in horses and sheep, inserted into the human genome in several places. The bornavirus is an RNA virus but not a retrovirus: it normally does not insert its genome into that of a host cell. The bornavirus genome has also been found inserted into the genomes of other mammals, with bornavirus "fossil" patterns common to us and other animals indicating that such insertions went back when we shared common ancestors. Using that as a very rough clock, the oldest insertions are about 40 million years old.

* DISCOVERY.com had an interesting little photo-essay on the Hawaiian bobtail squid, a charming little thumb-sized creature that has an interesting relationship with symbiotic bacteria. The bacteria, Vibrio fischeri, live in an organ provided by the squid; the microorganisms, which are luminescent, return the favor by illuminating the bottom of the squid so that predators looking up don't see a shadow going overhead.

The squids are active at night. In the morning, they eject a large portion of the bacteria, allowing them to "infect" other squids, and then bury themselves in sand to hide out for the day while their bacteria replenish themselves. Once the Sun goes down, the squid venture out, camouflaged by the bacterial light, which is reflected downward and, it seems, modulated to a degree to match lighting conditions by the structure of the organ in which the bacteria live. The squid otherwise does not need the bacteria to stay alive.

Incidentally, humans have tinkered with using illumination for camouflage as well. During World War II, the US rigged up aircraft with lights arranged so that they wouldn't be as easy to see from a distance in daylight conditions, allowing them to sneak up on German submarines cruising on the ocean surface before they could dive and escape. The scheme actually worked as planned, but nobody could figure out a really satisfactory way to mount the lights on the aircraft and it was judged generally impractical.

* There was a buzz in the science blogosphere concerning the "Dark Energy Camera (DECAM)", being developed by the US Fermi National Laboratory in Batavia, Illinois. The DECAM is no ordinary camera: it has a resolution of 570 megapixels, is cooled to -100 degrees Celsius, and is the size of a minicar. The DECAM uses an array of 74 CCD imagers to achieve its high resolution; it has to crunch so much data that it takes 17 seconds to obtain a single image. In 2011, the DECAM, will be installed in a 4-meter (157-inch) telescope known as the "Blanco" at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. Using the DECAM, the telescope will map the southern skies, obtaining floods of data on the reddening of light or "redshifts" of distant galaxies and other cosmic objects due to the expansion of the Universe. The detailed redshift maps are expected to provide new insights into the mysterious "dark energy" that seems to control the expansion rate of the cosmos.

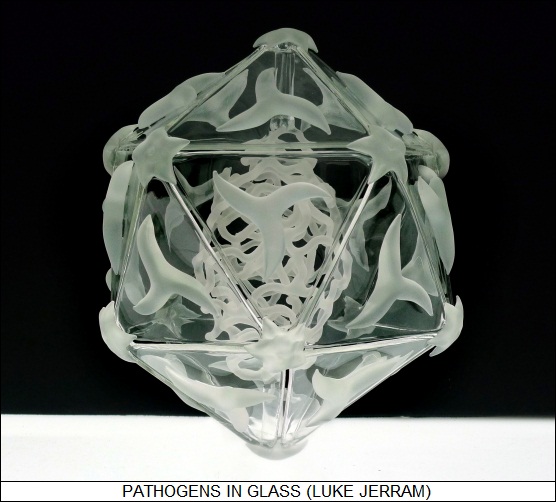

* While the arts and the sciences don't have a reputation for getting along well, there are those who do make the attempt to bridge the gap. One interesting example is UK visual artist Luke Jerram, who has taken to rendering pathogens -- the flu virus, HIV, and so on -- as glass sculptures. Jerram's work tends to illustrate the mixed feelings we have towards pathogens: as deadly as they are, they can be absolutely fascinating and even, to the properly tuned eye, downright beautiful.

COMMENT ON ARTICLE* VENTER DOES BIOFUELS: The rush to develop biofuels over the last few years seems to have slowed somewhat, partly due to fluctuations in oil prices and partly due to the fact that expectations for biofuels have proven a bit overblown. However, as reported in THE ECONOMIST ("Craig's Twist", 15 July 2009), oil giant Exxon is now investing $300 million USD in biofuel research and, if things seem to work out, may invest $300 million USD more. The money is going to Synthetic Genomics, a startup in San Diego, California, run by Craig Venter. Venter's credentials are good, since he ran Celera Genomics, the for-profit firm that helped decipher the human genome.

Synthetic Genomics has a different target: algae. Currently, biofuels are made by fermenting corn or sugarcane to produce ethanol, or processing plant oils to make biodiesel. Both processes leave something to be desired in terms of delivering a cost-effective product. Venter would like to "biomanufacture" fuels using algae that have been genetically modified to directly produce fuels with little or no additional processing.

Many startups are tinkering with biofuels from algae, some species of which produce oils that can be used for biofuels. One of the issues in this process is to get the oil out of the algae; Venter's team has managed to genetically modify algae so it actually releases the oil, which floats to the surface of the culture tank. The oil still needs processing to turn into fuel, and that's where the Exxon money comes in. The oil produced by the algae is a "triglyceride" that contains oxygen atoms, along with carbon and hydrogen; Synthetic Genomics plans to further tweak the genome of the algae to get rid of the oxygen, resulting in a pure hydrocarbon that could, in principle, be used as a fuel with no need for chemical alteration.

Once Synthetic Genomics has the genetic tweaks in place, the last task is to find a species of algae best suited for biomanufacturing, capable of handing intense sunlight and the associated heat so it can photosynthesize like mad. Since the algae will be cultivated in large batches, it will also need to be disease resistant. If no one algae species has all these desireable properties, Synthetic Genomics will cut-&-paste the genomes of several to come up with one that does.

Carbon dioxide will be needed to drive the growth of the algae, and since the atmosphere can't provide enough, it will be obtained from the exhaust of a power plant or other major industrial facility. Since the power plant is driven by coal or other fossil fuels, the process is not carbon-neutral -- the CO2 ends up escaping in the end when the biofuel is burned in an automobile or other vehicle. However, there's no additional carbon footprint from burning vehicular fuels obtained from the ground.

Venter believes that his biofuel scheme can turn out at least ten times more fuel per hectare than can be turned out from corn or sugarcane, and will not take up land needed for food production. That's not an entirely level comparison, since the production system for algae biofuels will be more complex and capital intensive, more like a chemical plant than a farm, and will need to be sited near power plants or other facilities to provide the CO2 -- though if it works out, admittedly a big "if", it might be profitable to simply build pipelines to pump the CO2 to the fuel synthesis plants. Right now it's a dream, but it can pay off sometimes to dream big.

* SCIENTIFICAMERICAN.com had several other articles on efforts in biofuels:

The last item included a comment that could apply to most biofuel efforts -- the researchers pointing out that at present what they have is essentially a blue-sky idea, one saying: "With R&D, it can look easy on paper, but you can run into all sorts of challenges."

COMMENT ON ARTICLE* WHO NEEDS DEMOCRACY? As reported by an article from THE ECONOMIST ("Crying For Freedom", 16 January 2010), international human rights activists have noticed an unsettling trend: democratic rule seems to be on the decline around the world. Twenty years ago, with the fall of the Soviet empire, it seemed like the rule of authoritarians had been given a sharp rap that would, thanks to the unfortunate lessons of the past, provide a new drive to liberalize societies with open elections, the rule of impartial law, respect for the rights of individuals, freedom of expression and association, and free enterprise.

Even then, the sensible were keeping their fingers crossed, understanding that a hopeful outcome is not an inevitable one. They were wise to be cautious. Many of the states that arose from the rubble of the USSR are authoritarian, some downright tyrannical, and authoritarian states are now collaborating on how to maintain their grip on power. Worse, democratic states have lost their bubbly optimism, and have even become somewhat apologetic.

That weary spirit of apology partly owes its origins to the US war to oust Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein, which early on was enthusiastically proclaimed as a campaign for democracy. That wasn't the way things worked, and in fact much of the world saw American talk of democracy for Iraq as a cover for overbearing imperialism. The attempt to set up a democratic regime in Afghanistan has similarly proven rocky, with the corruption of the Afghan government undermining efforts to bring peace to the country. In contrast, emerging China seems to show that authoritarian rule can work, with countries such as Syria and Cuba taking China as a role model. Many poor countries are also fond of China, since the Chinese are inclined to do business with them without pestering them about little defects, like miserable records on human rights and gross misgovernance.