* 21 entries including: genomic sleuthing, natural gas revolution, animal robots, bottom of pyramid business overstated, gorilla and bear genomes, polypill, Europe buying American trees for fuel, auto radars, trying to cut down on regulations, mechanical analog computers, and problems with organic farming.

* NEWS COMMENTARY FOR APRIL 2012: As reported by THE ECONOMIST, Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff visited Washington DC this last month, reciprocating American President Barack Obama's visit to Brazil last year. The meeting was cordial and pleasant -- as well it might be, since both nations are democratic, entrepreneurial, and committed to global stability. Obama has scored big points in Brazil for allowing duties on Brazilian ethanol to lapse, as mentioned here recently, eliminating a long-standing sore point, and also liberalizing the granting of entry visas to Brazilians, another old irritant.

However, the two nations still have substantial differences of opinion. At the root is the perception of Brazilians that the US doesn't take Brazil seriously enough. Rousseff didn't get a formal state dinner as had been recently conducted for British Prime Minister David Cameron; to be sure, there's no way Brazilians could sensibly think the Americans would regard relations with Brazil as on the same plane of significance as relations with Britain, but it was still perceived by some Brazilians as a snub. The reality was that Rousseff had specifically requested that the White House handle her visit at the same level of protocol as Brazil had handled Obama's visit.

Nonetheless, there are limits to how seriously the US really does take Brazil, and not without some reason: the US as a global superpower obviously doesn't estimate Brazil, with no real capability for force projection and lacking global political influence, as being in its league, and also sensibly classes Brazil on the second tier of nations of importance to the USA.

Brazilians would like America to endorse Brazil's bid for a seat on the UN Security Council. Britain has done so; so far, all Obama has done has made kindly noncommittal noises about the matter. The Americans have reservations about the zigs and zags of Brazilian foreign policy, as demonstrated by the efforts of Rousseff's predecessor as president, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, to co-broker with Turkey an anti-proliferation agreement with Iran's president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. The Americans were unenthusiastic, and the effort got nothing useful out of Tehran; Rousseff has distanced herself from that fizzle, but it left an impression in Washington DC that the Brazilians are just grandstanding and clowning around in their foreign policy.

The US is beginning to take Brazil more seriously, becoming aware that Brazil is a capable economic competitor, while Brazil's emerging economy offers profits to American businesses. On their side, which China now being Brazil's biggest trading partner, Brazilians don't have to take the USA as seriously as in the past.

Trade is really the number-one issue between Brasilia and Washington DC. One of the reasons for Obama to allow the ethanol import tariff to lapse was to encourage Brazil to open up its own markets -- but Brazil's businesses are doing all they can to keep competitors out, and the two nations don't see eye-to-eye at all about monetary policies. There's no trade war going on, Americans are doing a boom business with Brazil; still, for all the public agreeableness of Rousseff's visit to the White House, both sides have a fair list of gripes, and there's no prospect of major progress on them any time soon.

* Reflecting on the comments here last month about reform in Myanmar, in the wake of his visit to Washington DC, in mid-April British Prime Minister David Cameron visited Myanmar, to talk with Myanmar President Thein Sein, as well as opposition NLD party leader Aung San Suu Kyi -- Suu Kyi being flush with a resounding NLD victory in polls conducted on 1 April. After talks, Cameron made a pitch for suspending European Union (EU) sanctions against Myanmar, except for the arms embargo. Suu Kyi endorsed Cameron's initiative, meaning it's very likely to fly.

There is also very likely to be some irritation in Brussels over Britain's about-face on Myanmar, the UK having been one of the toughest advocates of sanctions in the past, but Cameron can make a good case for the turnaround. Cameron was also careful to suggest a "suspension" of sanctions, not simply lifting them; Myanmar has come a long way in the last year or so, but it has a long way to go, with hundreds of political prisoners still in lockup and the military still constitutionally entrenched in the government. Suu Kyi says that country has undergone "a revolution of the spirit", but suggests caution over expecting a "happy ending" soon. [ED: As of 2023, there wasn't.]

* Articles on international product counterfeiting have been run here in the past, the last in 2010, one unifying theme in them being the fact that China does the lion's share of counterfeiting. As reported by THE ECONOMIST ("Pro Logo", 14 January 2012), things may now be turning around -- the biggest reason being that Chinese are increasingly seeing counterfeit goods as unfashionable.

There was a time when Chinese didn't care about counterfeit as long as it was cheap, but now Chinese consumers are wealthier, more discerning, and more status-conscious, preferring the "real thing" to a cheap knockoff. A woman carrying a fake Gucci handbag is now a target of ridicule. A poll showed that the proportion of Chinese consumers who said they were willing to buy fake jewelry dropped from 31% in 2008 to 12% in 2011. Chinese consumers are realizing that brands are not just about showing off; they can also provide useful signals about quality. Brand recognition isn't just a matter of snobbery, either, given that some Chinese fakes are downright dangerous -- in contrast to say, a Coke, which is very unlikely to be toxic since it would do billions of dollars of harm to the Coca-Cola brand name if it was.

Of course, Chinese product counterfeiting is far from dead; if prosperous adults are now turning their noses up at fakes, cash-strapped youngsters still like them. In 2009, about roughly 30% of mobile phones in the country were thought to be "shanzhai", a slang term for a convincing fake. The Business Software Alliance, a global trade group, estimated that nearly four-fifths of the software sold in China in 2010 was pirated.

Still, China's counterfeiters are finding making a living increasingly difficult, and it's not just because of consumer snobbery. China is starting to shed its reputation as a manufacturer of junk, with Chinese brand names, such as computer-maker Lenovo and appliance manufacturer Haier, starting to obtain international reputations. The Chinese were willing to ignore intellectual property law as long as they stood to lose nothing thereby -- but now they do, and the authorities are under increasing pressure to clamp down on fakes. The authorities have announced that by 2013, counterfeit software will be gone from government offices.

Even cynical foreigners who have become accustomed to the Chinese talking tough about counterfeits and then doing nothing about them see things as changing. A survey by the European Union-China Chamber of Commerce suggests that counterfeiting, long the first or second most important concern of its members, is now third, fourth -- or not even on the list any more. It's not only due to changes in China's mindset: manufacturers have become much smarter about providing ID and tracking for their products, with some setting up their own retail outlet chains to ensure controlled distribution.

Indeed, some brand-name manufacturers can even see that product fakery gives them an opportunity. In December 2011, another scandal over tainted products popped up, this time over milk. Swiss food giant Nestle quickly announced that, working with local partners, the company will invest some $400 million USD to boost its dairy operation in China.

* As a footnote, I ran across a blog by a Western student in Beijing, it appears from his English writing style an American, who came across a Chinese hamburger chain named "QingQing Kuaican" AKA "QQ", his photos showing the chain's stylings having a distinct resemblance to those used by a certain global hamburger chain noted by its golden arches. The author says he's become fond of hanging out in the "MockDonald's", concluding: "I'm lovin' it!"

COMMENT ON ARTICLE* GENOMIC SLEUTHING (5): In another related tale of genomic sleuthing, as discussed in an article from THE ECONOMIST ("Plenty More Bugs In The Sea", 24 March 2011), at present all life on Earth is divided into three "domains":

At one time, there were thought to be only two domains, bacteria and eukaryotes, but in the 1970s it was recognized that one group of what had been thought of as bacteria had radically different biochemistry from the other, and so the prokaryotes were split into the bacteria and the archaea. The discovery of the archaea was a big surprise, the domain not having been noticed up to that time because biologists didn't have the tools to examine prokaryote biochemistry in enough detail. Given that the archaea had been hiding out just under our noses for such a long time, the question comes up: are there other domains of life hiding out under our noses as well? In a recent paper, Jonathan Eisen of the University of California at Davis and his colleagues suggest there may be at least another one.

The story begins with Craig Venter, one of the prime movers in the decoding of the human genome. In 2003, after some business difficulties, Venter decided to take a sabbatical in the form of a four-year cruise around the world in his yacht SORCERER II. The cruise was something of a working holiday, Venter taking time to perform "metagenomic" studies of sea microorganisms along the way.

Metagenomics involves examining the genomes of an entire ecosystem, or more specifically a part of one, at the same time. Venter's approach to metagenomics was based on a scheme called "shotgun sequencing" he had used to track down the human genome. In shotgun sequencing, a genome is shredded into chunks small enough for sequencing machines to rapidly digest, with the pieces then reassembled by matching overlaps between them using computer analysis.

Venter realized that shotgun sequencing could, in principle, be used to tackle genomic samples derived from a mix of organisms, and very sophisticated software might even be able to sort the genomes of the different organisms out from each other. Since only a small portion of microorganisms, some think no more than 3%, can be cultured and sequenced in the lab, there's no saying what metagenomic analysis of "wild" samples might come up with. In practice, metagenomic analysis has its limits -- for now, it tends to turn up fragments of genes, not complete genes. However, it has been very successful at identifying specific genes and unusual variants of them.

Eisen decided to use metagenomic analysis to scan through the samples taken on Venter's SORCERER II cruise to track down unusual gene variants. After some false starts, Eisen and his colleagues focused on two genes, RecA and RpoB -- the first being involved in DNA replication, the second in translating DNA into RNA. They are universal among known organisms, and so presumably very ancient.

Eisen constructed two trees, one of relationships between the RecA genes and the other of relationships between the RpoB genes, from the samples. The trees revealed branches not seen in trees derived from by known versions of the genes found in public genetic databases. That wasn't surprising; again, only a small proportion of microorganisms can be cultured in the lab, so finding something new in Venter's samples could be expected. Most of the new branches weren't all that surprising either, minor variations of known branches -- but there was one branch of the trees for RecA and RpoB that that seemed to come out of nowhere.

What organisms did the genes in this "mystery branch" come from? Since Eisen didn't have full samples of the organisms, he can't answer that question at present -- but he does have a hint to the possible existence of a fourth domain of life. Obviously, if there is such a fourth domain, it's been around since almost the beginning, and though we don't know anything about it, it may well be significant. After all, the archaea lurked around for decades without being recognized for what they were; a fourth domain of life may be similarly hiding from us in plain sight. [TO BE CONTINUED]

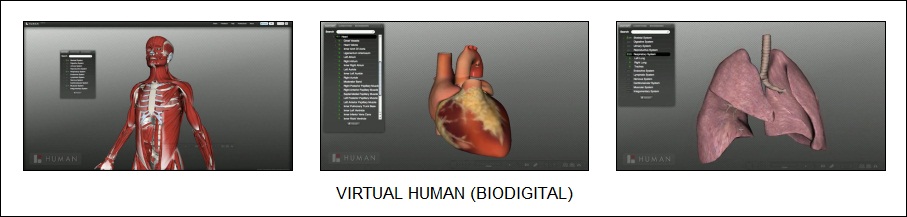

START | PREV | NEXT | COMMENT ON ARTICLE* GIMMICKS & GADGETS: As reported by BBC.com ("Pharmacy On A Chip Gets Closer" by Jonathan Amos, 16 February 2012), American researchers have tested a wireless body implant that dispenses drugs into patients on a programmed basis. The implant has been run through a trial with seven elderly Danish women suffering from the bone-loss disease osteoporosis, with good results. The patients found it much more convenient than their usual routine of drug injections.

The implant is about the size of a heart pacemaker, with dimensions of 3 x 5 x 1 centimeters (1.2 x 2 x 0.4 inches). Its core is a chip connected to an array of tiny wells, each well loaded with a dose of a drug. The wells are capped by a thin membrane of platinum and titanium; the membrane decomposes instantly when the chip fires a current through it.

The device started out as a research project at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and is now being developed by a spin-off company with the unimaginative name of Microchips INC. The firm is working to scale up the system so that more doses can be included; the trial system provided only 20 doses, but company officials believe hundreds are possible. The technology is not expected to ready for operational use for at least five years, but it is seen as having enormous potential. Professor Robert Langer of MIT commented: "You could literally have a pharmacy on a chip. This study used the device for the treatment of osteoporosis. However, there are many other applications where this type of microchip approach could improve treatment outcomes for patients, such as multiple sclerosis, vaccine delivery, for cancer treatment and for pain management."

* As discussed here last year, bedbugs are becoming a resurgent nuisance, not merely troublesome because of their bites, but because they're tiny and like to hide out, making them difficult to find. As reported by THE ECONOMIST, James Logan and Emma Weeks of the London School Of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine think they've found a way to lure bedbugs out of their hiding places: the smell of bedbug droppings.

Bedbugs zero in on the smell of their droppings, it seems in order to find their way back to their hideouts after biting a victim. The researchers chemically analyzed bedbug droppings to find out what chemical components the bedbugs were zeroing in on, and came up with a trap along the lines of the well-known "Roach Motel" -- a box with cockroach baits and a sticky floor to ensure that roaches "Check In But Don't Check Out".

* WIRED.com reports that the Asus company of Tapei has developed an intriguing modular approach to personal computing. The Asus scheme starts with the "PadFone", a fairly ordinary-looking smartphone running the Android 4.0 operating system on a 1.5 gigahertz dual-core processor and 1 gigabyte of RAM. Its distinction is that it snaps neatly into a 25-centimeter / 10-inch 1200x800-pixel touchscreen tablet docking station, the "PadFone Station". When docked, the PadFone provides all the smarts for the tablet, retaining use of its original wireless communications link and camera, while the Station provides speakers and an option for a headset to handle calls.

Now plug the Station into a keyboard dock and the thing becomes a little desktop computer. The PadFone system could end up being a silly gimmick, but the concept has potential for "bottom of the pyramid" computing. A smartphone isn't out of the reach of poor people; once they have the smartphone, if the rest of the system isn't too expensive, it's not out of their reach either. However, if the scheme remains proprietary to Asus, it will likely never be more than a gimmick; to really catch on would demand multivendor support, so a user could buy a smartphone from one vendor, a tablet docking station from a second vendor, and a keyboard from a third vendor. We'll see. [ED: As of 2019, it went nowhere.]

* As reported by BUSINESS WEEK ("A Static-Free Way To Zap Power Thieves" by Stephan Nielsen, 12 March 2012), Brazilian utility AES Eletropaulo of Sao Paulo is now enthusiastically embracing smart electric meters, finding them the solution to widespread electricity theft. Electricity theft is so common in Latin America that some statisticians have used it to estimate the size of a nation's informal economy. In Sao Paulo, the problem is centered in the city's notorious slums, the "favelas", and taking corrective action can be difficult -- people sent into a favela to figure out what's going on can end up getting hurt.

Smart meters, which use wireless to report their current status to a central server, end up fixing most of the problems. If they report an excess of power draw on a connection, it's probably being looted, and in any case the residence to which the meter is attached gets the bill. If they don't pay, the meter is commanded over wireless to shut off. Smart meters also eliminate collusion between users and meter readers, who are sometimes paid off to misreport meter readings.

When smart meters were installed in two notoriously dangerous favelas in Rio de Janeiro, electricity theft went from as high as 80% down to nothing. A Rio utility has installed 150,000 smart meters, estimating that they save the equivalent of $4.7 billion USD a year. With cutbacks in government programs to install smart meters in the USA, Latin America is looking like a boom market to smart meter manufacturers, with estimates of tens of billions of dollars in sales to 2020. Brazil is expected to account for the lion's share of sales, partly because of legislation now in process to require the installation of smart meters.

COMMENT ON ARTICLE* NO TREASURES AT THE BOTTOM OF THE PYRAMID? The notion of businesses targeting the "bottom of the pyramid", producing low-cost products to sell to the poor, has been discussed here in the past, with Indian firms having a global reputation for such efforts -- cheap cellphones, one-rupee packets of shampoo, and clever schemes to get around the lack of bank accounts. A survey of India's business environment in the 14 October issue of THE ECONOMIST corrected misperceptions -- for example, pointing out that while India has a reputation for freewheeling entrepreneurship, business is heavily dominated by family firms such as the Tata Group and state-owned firms, with Indian companies having an odd bent towards incoherent diversification -- and also pointed out the limitations of the "bottom of the pyramid" model.

It is certainly an inspiring idea, and Indian businesses are perfectly aware of how well it goes over with the public and the government. It also, unfortunately, has some things going against it. Consider Bharti Airtel, one of the major players in India's mobile phone industry. Mobile phones have been a true revolution for India's poor, providing them with communications and information access they couldn't have dreamed of before. However, this last summer Sunil Mittal, Bharti Airtel's boss, bluntly announced that it was no longer profitable to service rural customers -- it costs more to set up networks in the country than in the city, and there are fewer customers to in the country to service. In other words, India's mobile phone industry has hit the limits, and prices are now expected to slowly rise.

Mobile phones are not the only field where the limits of frugality are being reached. Tata Motors' Nano, a $3,000 car, was introduced in 2009 with a big splash, Tata having set up a factory in Sanand, Gujarat, to churn out 250,000 of the cars a year. Two years later, the factory is nowhere close to running to capacity. While sales projections were 20,000 cars a month, Tata's never sold more than 10,000 in a month, and in the worst month only a little over 500 cars were sold.

The Nano demonstrated many of the difficulties with the "bottom of the pyramid" business model. There was no sensible national distribution scheme for the car, little marketing and advertising, and no credible scheme for consumer finance. Poor folk saw it as still out of their reach, while pushing its low cost turned off more prosperous customers, who preferred the more sophisticated offerings by Tata rival Maruti, currently the top dog in India's small-car business. Tata has responded, offering an improved guarantee, setting up a consumer financing scheme with Indian banks, and ramping up advertising -- not only on TV, but via new drop-in showplaces to reach India's vast numbers of towns and villages.

Will that save the Nano? Maybe, but Tata seems to be after diminishing returns. In air travel, insurance, consumer finance and satellite TV, Indian companies have cut prices to build their customer bases over the past five years, only to find they ended up compromising on quality and still could not reduce costs enough to be profitable -- or as the old corporate gag has it: "We're taking a loss on each item we sell, but we hope to make up for it in volume." As in telecoms, the end result is likely to be price increases and the exit of the weakest players.

So is the focus on the "bottom of the pyramid" a mirage? Not at all, there's money to be made there, and there are also more abstract reasons to care about that business, such as a sense of social responsibility on one hand, and the desire to create a base of loyal customers who can be assisted to greater affluence and buying power on the other -- in a sense, it could be seen as a form of advertising. There's also the reality that figuring out how to build good but sell cheap through frugal engineering has a big potential in helping to sell to customers higher on the pyramid. Companies such as General Electric (GE) and Tata's chemical arm have embraced frugal engineering concepts to manufacture cheap products with great success. GE, for instance, has developed basic medical scanners in India and now sells them in the West.

However, the upper levels of the pyramid are where the real profits are. If Indian businesses want to be profitable, they need to target more affluent buyers who can spend more. Today about 17% of India's population has half of its spending power, the growing urban middle class is becoming wealthier rapidly -- and it's not as hard to sell to people in cities than it is in the country, where buyers are much more widely spread and infrastructure is lacking. If that's where the money is, that's where the business needs to go.

Does that mean Indian businesses are going to forsake the poor? No, as mentioned above there's some principle in providing services to them, and there's still money to be made in doing so. In contrast to the stumbling Nano, Renault-Nissan has been making the low-cost Logan in Romania for some years and is selling them at the rate of 400,000 a year -- with a higher profit margin than for other Renault-Nissan products. Still, the inherent challenges of selling to the bottom of the pyramid puts boundaries on just how much Indian companies can do there, and it is likely to be a secondary focus for most of the players, pursued to the extent it doesn't demand major resources to do so.

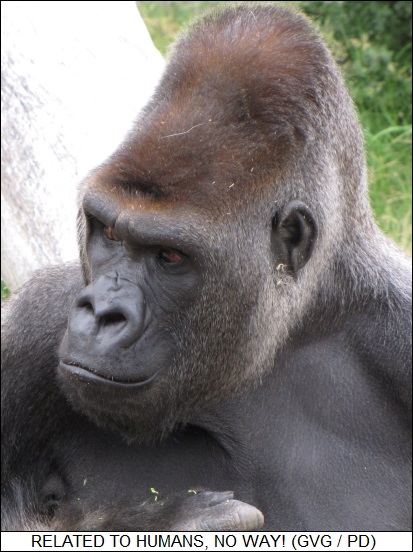

COMMENT ON ARTICLE* GORILLA GENOME: As discussed in an article from AAAS SCIENCE NOW ("A Little Gorilla In Us All" by Elizabeth Pennisi, 7 March 2012), once we obtained the ability to sequence the genomes of animals, one of the high priorities was the decoding the genomes of our closest relatives, the great apes. Says paleoanthropologist David Begun of the University of Toronto in Canada: "It will allow us to begin to identify genetic changes specific to humans since our divergence from chimps."

There are four modern groups of great apes: chimps and bonobos, humans, gorillas, and orangutans. The genome of the chimp, our closest relative, was published in 2005; the orangutan sequence came out in early 2011. Now researchers have obtained the genome of a female western lowland gorilla named Kamilah, a resident of the San Diego Zoo, and have sequenced DNA from three other gorillas, including one individual of the rare eastern lowland gorilla.

As discussed in a paper by a research team led by investigators from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Hinxton, UK, and published in the prestigious journal NATURE, humans and apes are nearly identical at the genetic level: the human genome is 1.37% different from the chimp's, 1.75% different from the gorilla's, and 3.4% different from the orangutan's. What is particularly interesting is that, though overall the human genome most closely matches that of the chimp, 15% of the human genome more closely matches the gorilla genome -- while a different 15% of the chimp genome more closely matches that of the gorilla genome than the human. According to Sanger evolutionary genomicist Aylwyn Scally, there's a similar pattern of similarities in gene action: "Some of our functional biology is more gorillalike than chimplike."

That may seem a little strange, but on consideration, it makes sense: gorillas, chimps, and humans all share a single common ancestor, and chimps and humans simply retained different shares of the common ancestral genome that ended up in the gorilla. Suppose gorillas, chimps, and humans have the following sets of genes:

[GCH] genes shared by gorillas, chimps, and humans (the bulk of genes) [GC] gorilla genes shared with chimps but not humans [GH] gorilla genes shared with humans but not chimps [G] genes unique to gorillas [CH] chimp genes shared with humans [C] genes unique to chimps [H] genes unique to humans

It is straightforward to then trace the inheritance of these groups of genes back to a common ancestor. To be sure, genes unique to gorillas, chimps, or humans will include a component that was acquired during their evolution from a common ancestor, but they will also include a component inherited from a common ancestor; the acquired component is usefully ignored in this analysis. Anyway, we have the following patterns of genes for gorillas, chimps, and humans:

[GCH][GC][GH][G] -- gorilla [GCH][GC][CH][C] -- chimp [GCH][GH][CH][H] -- human

Lumping the gene sets for the common ancestor of chimps and humans gives the pattern:

[GCH][GC][GH][CH][C][H] -- chimp & human

That reverse accumulation of gorilla genes means the common ancestor was more gorilla-like than either modern chimps and humans. Going back to the common ancestor of all three gives, of course:

[GCH][GC][GH][G][CH][C][H] -- gorilla & chimp & human

The fact that we have more chimp genes shows we are more closely related to chimps than gorillas, there's been less dilution down the line of descent. It wouldn't be a surprise to find we have a number of genes more in common with baboons than chimps, but if so they're certain to be small in number, being much more diluted.

With all the great ape genomes to compare, researchers are now better able to estimate when gorillas, chimps, and humans diverged from each other from common ancestors. Molecular data suggests that humans and chimps trace back to a common ancestor about 4.5 million years back, but fossils that old seem to already demonstrate a split, with some paleontologists saying the two species went their separate ways up to 7 million years ago. The Sanger group estimates that the split took place about 6 million years ago, using as an adjustment a recent finding that the mutation rate may have slowed over time in ape evolution. Scally also points out that interbreeding between proto-chimps and proto-humans could have delayed the visible separation of the genomes of the two lines. The paper suggests that the gorilla line split off from the chimp-human line about 10 million years ago.

The genome comparisons show that more than 500 genes in all three lines have been mutating faster than expected, suggesting selection pressure on those genes. In the gorilla, one of the faster-evolving genes involves in the hardening of skin, as happens in gorilla knuckle pads, used for knuckle walking. Hearing genes that have evolved rapidly in humans also show accelerated evolution in gorillas, as do the evolution of genes for brain development in both gorillas and humans. Chris Tyler-Smith of the Sanger group commented: "Our most significant findings reveal not only differences between the species reflecting millions of years of evolutionary divergence, but also similarities in parallel changes over time since their common ancestor."

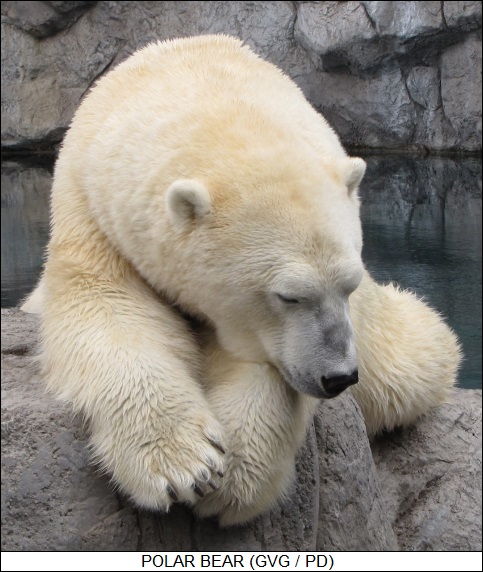

* In a related story of genomic analysis, according to an article in THE NEW YORK TIMES ("Investigating Mysteries of Polar Bears' Ancestry With a DNA Lens" by James Gorman, 2012), genetic analysis of bear DNA was once thought to show that polar bears are descendants of brown bears, having branched off from brown bear stock about 150,000 years ago to acquire white coats, webbed paws and other adaptations for their Arctic existence.

That was determined by examination of bear mitochondrial DNA, which exists outside of the cell nucleus and which is only passed down through the maternal line of descent. Mitochondrial DNA is relatively short and easy to sequence, but it can give misleading results, and it seems it did so in this case. A group of researchers, including Axel Janke and Frank Hailer of the Biodiversity and Climate Research Center in Frankfurt, Germany, performed a more thorough DNA analysis on 14 stretches of nuclear DNA in samples taken from 19 polar bears, 18 brown bears and 7 black bears, to determine that brown bears and polar bears split off from a common ancestor about 600,000 years ago.

The analysis suggests that polar bears have suffered through warming periods and disappearance of sea ice in the past, squeaking through "evolutionary bottlenecks" that reduced populations and genetic diversity. Why did the mitochondrial DNA analysis give such different results? The likely reason is that a female brown bear interbred with a male polar bear about 150,000 years ago, and her female descendants eventually predominated, spreading their mitochondrial DNA through the population -- though her nuclear brown bear genes ended up being diluted.

COMMENT ON ARTICLE* INVASION OF THE ANIMAL ROBOTS (1): As reported by an article from THE ECONOMIST ("Zoobotics", 9 July 2011), the classical concept of a robot is of an artificial human, there being a distinct bias against other organisms. In the 21st century, however, robotics researchers are becoming very interested in emulating the wide range of configurations available in the animal kingdom, both to learn more about animals, and to evaluate the practical possibilities of machines that work like them.

Of course, robots have long been built that resemble animals, robot dogs being a common cheesy prop in sci-fi shows; SONY even commercially sold a robot dog named the Aibo. In the 1990s, robotic researcher Rodney Brooks of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) developed a series of insectlike little robots to investigate simple algorithms for intelligence, and there are plenty of robot insect toys on the market.

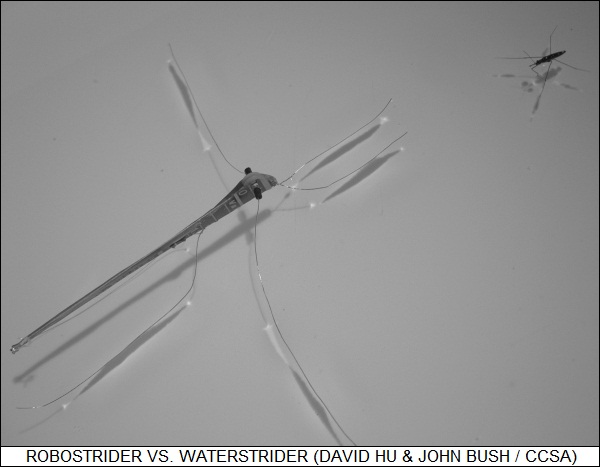

These machines simply used animals as inspiration, and were not specifically designed to simulate animal actions. Serious work on robotic analogs of animals began about a decade ago. One early example was a robot water strider bug, developed by a research team under John Bush at MIT. The "Robostrider" had the same general configuration as a water strider, with a long thin body and six legs, but it was about ten times bigger, with a length of 9 centimeters (3.5 inches). It was built of aluminum and steel wire, and powered by a windup elastic thread. One of the goals in the study was to figure out how water striders get around on disturbed waters, with the research team determining that the legs needed to generate vortices in the water to allow them to get better traction.

In the current day, Cecilia Laschi and her team at the Sant'Anna School of Advanced Studies in Pisa, Italy, are leading an international group working to construct an artificial octopus. Laschi's group has been designing an artificial equivalent of an octopus tentacle. The octopus tentacle has no bones, which means it lacks rigidity, but by that same coin it is also extremely flexible. The Italian researchers want to build a tentacle of their own with similar flexibility -- featuring an outer skin of silicone, wired with pressure sensors to give the tentacle a sense of touch, along with an internal structure consisting of cables and springs made of a highly elastic nickel-titanium alloy. The artificial tentacle has an uncanny resemblance to the real thing; Laschi's team is now working towards clustering eight of them and figuring out how to coordinate their actions.

Another robotics team at Sant'Anna, led by Paolo Dario and Cesare Stefanini, is working on an artificial lamprey. Lampreys are eel-like fish, but they are much more "primitive" than eels, in the sense that they have features going back much further in evolutionary history. They are cartilaginous, lacking bones and jaws, with a relatively simple nervous system that can be seen as a base model for more elaborate nervous systems on the path to our own. Sten Grillner's group at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm has been studying lampreys, leading to an interest in acquiring a robot analogue in hopes that it will provide insights.

Dario and Stefanini's team has obliged by developing the "Lampreta" robot. It consists of a series of circular segments, with each segment featuring an electromagnet, with the electromagnets segments activated by a current that flows from head to tail in a way similar to how a nerve impulse travels through a real lamprey. As each segment is activated, it attracts and then releases the next segment, resulting in a wavelike motion that propels the robot forward. The Lampreta also has little cameras for eyes, with one of the goals of the project being to enable the robot to interpret shapes and colors in its environment to allow it to navigate through it. That is being done as an end in itself, a tool for understanding how animals get around, but it certainly has applications in developing smarter and more useful robots as well.

Daniel Germann of the University of Zurich in Switzerland is building a robot to investigate an even less dignified animal, the clam. Clams have hinged "bivalve" shells and a foot, which wouldn't seem to buy them much, but they can use their hardware and jets of water to rapidly burrow into soft sediments when attacked by predators. Germann's robot clam features bivalve shells actuated by two strings, as well as a little pump to jet water; he's still trying to figure out the foot. Once he's got a working robot clam, he intends to run competitions between different shell shapes to see what advantages one shape has over others. The contenders will include extinct clam forms that apparently weren't efficient enough to compete, and so died out. [TO BE CONTINUED]

NEXT | COMMENT ON ARTICLE* GENOMIC SLEUTHING (4): Having obtained microbial samples from environments, researchers working on indoor ecologies then turn to software to help match up the microbial DNA sequences with known bacteria, and the environments in which such microorganisms are found. With the falling cost of sequencing, databases of microbial DNA have exploded, providing resources that allow researchers to determine if the microbes found indoors come from soil, outside air, humans, other animal occupants, or some other source.

Using such tools, Noah Fierer's group at UC Boulder was able to identify the likely sources of microbes from surfaces in a dozen public restrooms. The results weren't surprising:

For the BioBE's latest project, Jessica Green and her colleagues at the University of Oregon methodically cased out a campus building. They collected air from six rooms at different times of day; gathered dust from each of the building's 300-plus rooms to map out microbial distributions; and within each room chose different "habitats" -- floors, walls, desktops, and seats -- to perform sampling using square plots much like those traditionally used to investigate plant biodiversity.

One of the objectives of this ongoing investigation is to obtain an understanding of the relationships between microbial diversity with building design and use. The research group suspects that the patterns of diversity in the building resemble the biodiversity patterns of island groups, a well-studied topic. Each room can be seen as like an island, a self-contained environment, with the rooms linked to each other through ventilation and movement of occupants. If this "island model" proves useful, it might help guide building design and management to help control the dispersal of microbes from room to room.

One consideration along such lines is that, as buildings have been increasingly adapted for energy efficiency, they have become increasingly sealed off from outside air. The BioBE group has been trying to understand the implications of such reduced air exchange, sampling mechanically ventilated rooms with the windows closed and then the windows opened. When the windows were left open, not surprisingly microbes from the outside air increasingly predominated; when they were shut, the concentration of microbes originating from humans increased, resulting in lower microbial diversity. Green doesn't have the data to know if that is a good or bad thing from a health standpoint; she would like to conduct similar studies in a hospital to see if she can establish a relationship between hospital-acquired infections and microbial diversity.

* Jordan Peccia, an environmental engineer at Yale University, is performing studies under Sloan Foundation funding to investigate how air circulation in buildings affects microbes. As airborne material, bacteria tend to act just like inert dust particles, with size determining how they disperse and settle. Human occupants of a room not only shed microbes from their skin and mouths, they also scuff them up from the floor as they walk around.

To perform the study, Peccia's team had to devise methods to collect airborne bacteria and extract their DNA, airborne bacteria of course typically having much lower concentrations than those found on surfaces, making them harder to sample. In one recent study, the research group used air filters to sample a classroom for four days in which students were present and four days when the room was vacant. By factoring in the effect of ventilation, the group determined that people shed or kicked up about 35 million bacterial cells per person per hour. Not surprisingly, the study also suggested rooms have "memories" due to the kicking up of microbes left by previous occupants. Peccia wants to provide data to help design healthier buildings: "My hope is that we can bring this enough to the forefront that people who do aerosol science will find it as important to know biology as to know physics and chemistry."

However, Peccia doesn't feel that the science of indoor microbial ecology has come together yet, and the Sloan Foundation's Paula Olsiewski tends to agree: "Everybody's generating vast amounts of data", but right now there's not much standardization between how the investigations are conducted, making their results difficult to compare. Sloan is currently driving development of a data archive and integrated analytical tools to help bring order to the field. The foundation has also sponsored a symposium and set up a website, "MicroBE.net". Participants in the indoor microbial ecology effort are optimistic that they will be able to establish their work as a respected scientific discipline, and hopeful that it will yield practical benefits. [TO BE CONTINUED]

START | PREV | NEXT | COMMENT ON ARTICLE* March was a quiet month for space launches:

-- 23 MAR 12 / ATV 3 -- An Ariane 5 ES booster was launched from Kourou to put the third ESA "Automatic Transfer Vehicle (ATV 3)" AKA "Edoardo Amaldi" unmanned cargo spacecraft into space on an International Space Station support mission. It carried a payload of 6.5 tonnes (7.15 tons). The spacecraft docked with the station on 28 March. Two more ATVs will be launched, the program to end following the fifth launch.

-- 27 MAR 12 / INTELSAT 22 -- A Proton M Breeze M booster was launched from Baikonur to put the "Intelsat 22" geostationary comsat into space. It was built by Boeing and was based on the Boeing 702MP comsat bus. Intelsat 22 had a launch mass of 6,250 kilograms (13,780 pounds), had a design life of 15 years, and carried a payload of 48 C / 24 Ku band transponders to provide communications services over the Old World. It also carried a military UHF communications payload for the Australian Defence Forces, part of which was to be used by the US Navy.

* OTHER SPACE NEWS: The Intelsat 22 spacecraft and its military payload reflect a trend towards "hosted" satellite payloads -- government-funded payloads carried on commercial satellites. As reported by AVIATION WEEK, the satellite's military UHF communications system is to be used to support Aussie forces in the Middle East and South Asia. Australian government officials say it cost only about half as much to have the payload hosted than it would to have flown it on a fully government-owned spacecraft.

The US military demonstrated a similar interest in hosted payloads last fall, when the US Air Force flew the "Commercially Hosted Infrared Payload (CHIRP)" on the SES 2 geostationary comsat, CHIRP being a test article for a missile launch warning and tracking system. Last summer the Air Force set up a hosted-payload office to coordinate hosted-payload efforts; satellite vendors say there haven't been many contract awards so far, but they're getting plenty of inquiries, both from the Pentagon and from NASA. It seems likely that comsats will be designed specifically featuring secondary payload facilities.

As noted here in the past, the Iridium low-orbit comsat organization is now preparing its "Iridium Next" replacement constellation for launch from 2014, with the satellites being designed to accommodate hosted payloads of up to 50 kilograms (110 pounds) total. Orbital Sciences Corporation has been working with Iridium on a scheme where a fifth of that capacity would be used to carry an "Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B)" payload to set up a global aircraft tracking network. Orbital would offer the service under government contract, or at least that's the idea, there being no formal commitment to the deal just yet.

* AVIATION WEEK reports that Boeing Satellite Systems has now inked deals to supply the very first "BSS 702SP" geostationary comsats to customers, this model of satellite breaking new ground by using an all-electric propulsion and thruster system based on xenon ion engines. Comsats using electric thrusters for station-keeping are nothing new, but the 702SP also features electric propulsion for its main engine system.

A geostationary satellite is launched into an elliptical "geostationary transfer orbit" by a booster, and then "circularizes" its orbit using its own main propulsion system. Electric drives being very fuel-efficient, they can cut the weight of a satellite considerably, it appears up to half, meaning reduced launch costs. It also means it's not so important to launch a geostationary satellite from an equatorial site such as Kourou, since it doesn't require so much spacecraft fuel to shift the plane of an orbit.

The tradeoff is that electric drives have very low thrust. It usually takes a few weeks to get a comsat into its proper orbit and working; with electric drive, it can take up to six months, and during that time the spacecraft is not making any money. The reduced launch costs may be worth the delay, but the loss of revenue may be hard for smaller operators to swallow.

COMMENT ON ARTICLE* TAKE YOUR POLYPILL: As reported by an article from AAAS SCIENCE ("Experts Debate Polypill: A Single Pill For Global Health" by Sara Reardon, 30 September 2011), in 2003 Nicholas Wald and Malcom Law, cardiologists at Queen Mary, University of London, published a paper with a modest proposal. Heart patients often have trouble remembering to take all the drugs they need, and people in poor countries have trouble getting their hands on drugs at all. So, the two researchers suggested, why not just combine a set of cheap and useful drugs into a single pill -- a "polypill" as they called it? They used as an example a polypill made up of six common drugs and estimated that it would cut the incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in those who took it by 80%.

It seems like an entirely obvious idea, but there was considerable skepticism over the polypill, the idea coming across as too gimmicky, too simplistic. Now the polypill is starting to gain traction. Several manufacturers are making polypills, and clinical trials for polypills seem to be going well so far -- with patients displaying lowered risk factors like blood pressure, and few side effects. Advocates believe that widespread use of polypills would substantially reduce mortality from heart disease.

But who should take them? Critics don't like the idea of encouraging healthy people to pop pills; it doesn't seem like a good use of resources, and assuming that there would be no side effects seems like asking for trouble. However, Salim Yusef of McMaster University in Hamilton, Canada, takes an expansive view of the utility of polypills, saying that they could be appropriate for anyone over 55 with CVD risk factors, such as obesity. Yusef has been performing trials in India with a "Polycap" containing four heart drugs. His discussions with Indian pharmaceutical manufacturers suggest that in volume production, the Polycap would only cost 16 cents a capsule.

Simon Thom -- a clinical pharmacologist who is leading a UK branch of an international collaboration named "Single Pill to Avert Cardiovascular Events (SPACE)" -- takes a more limited view of the utility of the polypill, believing that the best targets, at least for now, are those who have "already put their hand up" with a heart attack or stroke. SPACE has already performed an international placebo-controlled trial with 378 test subjects at high risk of CVD, demonstrating a 60% drop in heart disease.

Cardiologist Richard Stein, a spokesman for the American Heart Association, cautions that much bigger and longer trials will be required to validate the utility of the polypill, with thousands of subjects tracked for at least a decade. Side effects, Stein said, might take five years or more to become noticeable. Cardiologist Allan Taylor of Georgetown University in Washington DC is dubious of the "one size fits all" aspect of the polypill, pointing out that aspirin is a potentially useful polypill component, but that there's a large number of patients that don't handle aspirin well. But for poor countries, Taylor doesn't have an objection: "I can totally see the rationale."

Cardiologist Elsayed Soliman of Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, is convinced that the polypill is a great idea for developing nations. Soliman is leading a feasibility study funded by the United Nations World Health Organization, and has received overwhelmingly positive feedback from doctors in poor countries. To the extent the feedback's been negative, it's been from doctors in rich countries oriented towards personal care of patients, and from pharma companies that aren't crazy about making cheap pills. Says Soliman: "In developing countries, where medicines are desperately needed, the debate is not there."

Soliman still doesn't believe that it would be economically feasible to give even cheap polypills to everyone over 55, preferring to develop a range of polypills with different dosages and costs for patients at different degrees of risk. As for the critics who worry about encouraging "pill popping", even polypill advocates agree that the polypill can only be part of a health care solution, along with encouraging a healthy lifestyle.

COMMENT ON ARTICLE* EUROPE BURNS AMERICA'S TREES: As reported by an article from IEEE SPECTRUM ("Europe Looks to North America's Forests To Meet Renewable Energy Goals" by Peter Fairley, April 2012), US forestry companies are doing a boom business with Europe, thanks to European Union (EU) goals for renewable sources to meet 20% of energy demand by 2020 and for a 20% percent cut in greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 levels. Using wood pellets from North American trees help fuel coal-fired power stations is an increasingly popular strategy to meet the EU targets. However, there are concerns that this strategy isn't quite as "green" as it might seem.

For the moment, the North American biomass industry is expanding rapidly, particularly in the southeastern United States, where giant pelletizing plants are springing up to convert trees into fuel for export. In 2011 the power company RWE of Essen, Germany, commissioned the world's biggest wood pellet plant, near Waycross, Georgia. The plant dries, crushes, and presses wood from local pine tree plantations into 750,000 tonnes of pellets a year, the output being destined for RWE power plants in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom.

US-based biomass firm Enviva, based out of Bethesda, Maryland, is also busily exploiting the demand for biomass fuel. The firm has recently begun shipping pellets from its plant in Ahoskie, North Carolina; the Ahoskie plant can turn out 350,000 tonnes of pellets a year. Enviva is now building an even bigger plant nearby in Northampton County, North Carolina, and is planning still another in Courtland, Virginia. The demand is there, Eviva having signed a contract to supply 480,000 tonnes of pellets a year to Belgium-based Electrabel, a subsidiary of the Paris-based GDF Suez Group, along with another contract to supply E.On of Germany with 240,000 tonnes of pellets annually.

RWE estimates that the pellets from its Georgia plant will reduce emissions by more than a million tonnes of CO2 per year. That assumes, of course, that trees really are carbon neutral, and so far most regulators have agreed with the endorsement of the Society of American Foresters, which published a study in the JOURNAL OF FORESTRY last year asserting that such a straightforward accounting is reasonable in the United States, where forest inventories have grown year over year since the 1930s.

Critics point to difficulties, most significantly the fact that a "surge" in biomass burning, as we're seeing now, will mean a rise in CO2 emissions over the short term that will not be quickly soaked up again by new biomass growth. A recent study commissioned by the US National Wildlife Federation and the Southern Environmental Law Center modeled proposed biomass industry expansion in the southeastern United States. In the study scenario, export-driven pellet production jumps from nearly 1.8 million tonnes to more than 3 million tonnes, while the number of local biomass power plants -- burning mostly forestry leftovers and other waste biomass -- more than doubles from 17 to 39. On that basis, it would take 35 to 50 years to achieve CO2 break-even.

Other studies along such lines suggest the break-even would be even longer for trees harvested from slower-growing northern forests. The obvious and exasperated counter-question is, of course, whether it would then be wiser to still go on burning coal. Still, the fuel pellet export boom is being driven by its green credentials; if those credentials don't hold up to scrutiny, it may come to an abrupt halt.

COMMENT ON ARTICLE* NATURAL GAS REVOLUTION (5): As a footnote to this series, as reported by an article from THE NEW YORK TIMES ("US Inches Towards Goal Of Energy Independence" by Clifford Krauss & Eric Lipton, 22 March 2012), it's not just America's natural gas business that's booming; domestic drilling for oil is on a roll as well. US oil production declined from a high of 9.6 million barrels per day (MBPD) in 1970 to 4.9 MBPD in 2008, but since then it's rebounded to 5.7 MBPD, and the US Department Of Energy (DOE) thinks it should reach 7 MBPD by 2020.

Part of the reason for the boom is improved drilling and production technology, but it's more due to high oil prices that make fields that would be uneconomical to exploit at low oil prices now very profitable. The boom has been aided by government policies, first implemented in the Bush II Administration and continued by the Obama Administration. President Obama's embrace of US oil represents at least a partial turnaround from his environmentally-oriented campaigning in 2008, and environmentalists have not been all that happy with him on that score.

The heart of the boom is the flatlands of West Texas, most specifically the region known as the "Permian Basin", which did much to fuel the Allied cause during World War II. After the war, however, the easy pickings there gradually dried up, going into a stall in the 1980s. There was still plenty of oil left, however -- if someone just knew how to get at it. In 2003, a West Texas oilman named Jim Henry ran a test hole and used fracking to successfully extract oil from a deep, hard limestone formation.

The problem was that the scheme was only profitable if oil was selling predictably at $60 USD a barrel or more, and the price at the time was $30 USD a barrel. However, it didn't take much vision to realize that the price of oil was going to rise, and the Bush II Administration did all it could to encourage oil exploration:

There was much in these actions to make many people unhappy, particularly environmentalists, as well as others who didn't much care for the "free ride" the oil companies were getting from the government. The oil companies were of course enthusiastic, and when the global oil crunch began to bite from 2005, they ramped up domestic exploration rapidly. The new wells were boosted not only by fracking, but by other improvements in technology, such as seismic probes to find deep deposits previously hidden under salt layers, and superhard drill bits to drive holes deep into the earth.

On entering office, in response to the criticisms against the US oil industry, Barack Obama cut back on leases and demanded stronger environmental review, but under the pressure of the oil crunch, Obama began to promote drilling as did his predecessor -- with the drive only paused by the 2010 accident at the Deepwater Horizon oil platform in the Gulf of Mexico, which killed 11 people and generated a huge oil spill. Obama simply had read the writing on the wall, to recently counter Republican attempts to blame him for high fuel prices in a March campaign appearance: "Our dependence on foreign oil is down because of policies put in place by our administration, but also our predecessor's administration. And whoever succeeds me is going to have to keep it up."

The Obama Administration has been more conscientious about environmental impact than the Bush II Administration, but that's a low standard of comparison, and the ugly truth is that the environment is a second priority compared to drilling more oil. It's not just simple greed, either: the USA lives on oil, and if we've got to have it, on the balance it's more attractive to drill it here than to import it. After all, if oil production is inherently bad for the environment, by relying on imports we're just shifting the problem to somebody else's backyard, where we have no control over matters.

To be sure, that's something of the reasoning of a junkie; but environmentalists can at least obtain some gratification that the Obama Administration is serious about conservation. The Bush II Administration was hostile to conservation, seeing it as ineffectual "do-gooderism", but to an extent conservation has been forced on Americans whether they like it or not as gas prices rise. Now Americans are buying more fuel-efficient vehicles and are less fond of long commutes. However, technology is pushing energy efficiency as well. Instead of running around town for a particular item, we can order it conveniently from Amazon.com and have it delivered to our door. More significantly, the Obama Administration realizes in a way the Bush II Administration didn't just how sophisticated 21st-century technology really is. 20th-century machines operated on brute force; now we are increasingly understanding how to "work smart not hard" and get things done much more efficiently.

Taken as a whole, given domestic natural gas and oil production, increasing use of renewables, and greater conservation, the USA seems to be finally moving towards a goal that American presidents have sought since the Nixon Administration: energy independence. Oil imports have declined from a high of 60% of America's total fuel usage to 45% in 2011. That's partly due to the economic downturn, but still, the trendline is definitely in the right direction. The way the gains are being made is not in all ways satisfactory, but humans are resourceful -- and taking an optimistic viewpoint, in another generation or two people may look back on the energy insecurity of our era and wonder what the fuss was all about. [END OF SERIES]

START | PREV | COMMENT ON ARTICLE* GENOMIC SLEUTHING (3): The notion of "disease weather maps" of the distribution of microorganisms in buildings and public places was mentioned earlier in this series. An article from AAAS SCIENCE ("Indoor Ecosystems" by Courtney Humphries, 10 February 2012) shows that exercise as an aspect of a wider effort to assess the microecology of human living spaces.

A few years ago Noah Fierer, a microbial ecologist of the University of Colorado at Boulder, spent his time investigating the microecology of soils and leaf letter. Fierer then expanded his scope to consider the microecology of humans -- their internal and external microbial hitch-hikers -- and how it was reflected in items such as computer keyboards. Fierer finally realized that nobody had really investigated the biodiversity of indoor spaces in a comprehensive way; now Fierer and Rob Dunn, an ecologist at North Carolina State University in Raleigh, have begun a "crowdsourced" research project to do just that.

The analysis of one ordinary household revealed a range of microbial species. Countertops were biodiversity hot spots of bacteria and fungi, including "sphingomonads" possibly derived from tapwater. The toilet seat was coated with bacteria derived from human skin, while doorsills were crawling with fungi and grass pollen. The front doorknob and the TV screen, of all things, were inhabited by unusual bacteria not usually found in water, soil, or the human body. Fierer and Dunn plan to perform similar surveys of thousands of households around the world, in hopes of understanding how such microbiomes vary in different locales or in different configurations of homes -- freestanding homes versus apartments, for example.

The two researchers are at the leading edge of a drive to understand the microecology of indoor spaces; genomics is only part of the effort, which also involves microbial ecology, indoor air science, and building engineering. Researchers are now scouring classrooms, offices, and hospitals to find out what lives in them. So far the work has been mostly driven by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the organization having spent $23 million USD on such work since 2004. According to Sloan program director Paula Olsiewski: "We thought it important to study where people live."

Surveys show that people spent 90% of their lives indoors, but as Jessica Green of the University of Oregon in Eugene points out, most research on the "ecosystems in which we spend 10% of our time." Green, a microbiologist by trade, heads the "Biology & the Built Environment (BioBE)" Center, set up in 2010 through a $1.8 million grant from the Sloan Foundation.

Obviously indoor ecologies have a major impact on our health. For example, air circulated by heaters and air conditioners can spread infectious diseases, and some cases of "sick building syndrome" is caused by rogue molds. Fungi in buildings is also linked to allergies, asthma, and other pulmonary conditions. Microbes even affect the structures themselves, breaking down wood, stone, concrete, and other materials. Despite the need to understand what organisms live in indoor structures, until recently nobody's known much about it. As a result, homeowners and building managers spend considerable time and effort cleaning surfaces and filtering air, without having much idea if it accomplishes anything or not. Building designers are similarly in the dark.

Green is well-equipped to investigate such matters, having originally started out to become a civil engineer and ending up with a doctorate in nuclear engineering. She then switched to microbial ecology, investigating biodiversity in soils and the seas before coming to Oregon. Inspired by the sustainable building program at the U of O and the prospect of Sloan support, she joined forces with two university colleagues, microbiologist Brendan Bohannon and architect G.Z. "Charlie" Brown, to launch BioBE.

One of the challenges faced by researchers in the new field of indoor microbiology is that it is indeed a new field, and people working on it don't quite exactly know how to tackle the job. They also have found that not everyone is impressed by their work. Physicist Ernest Rutherford once commented that all science was either physics or stamp collecting, and to some indoor ecology research looks uncomfortably like stamp collecting. One critic said that they were "just getting a list." Fierer, clearly exasperated, responds that "without that basic knowledge, it's hard to take the next step." [TO BE CONTINUED]

START | PREV | NEXT | COMMENT ON ARTICLE* SCIENCE NOTES: Jumping spiders have good eyes; they need them because they hunt by sight. However, along with clear vision they also need good depth perception, and that wouldn't seem so straightforward given the short spacing between their two main eyes -- typically, spiders have two big eyes flanked by six small eyes, the small eyes being used for peripheral vision.

One of the puzzles of jumping spiders is that their retinas had four layers. Nobody could quite figure out why this was so, but Japanese researchers have conducted studies that show the four-layer retina provides depth perception. The different layers of the retina are sensitive to different colors of light; since different colors of light are refracted at different angles by the lens of the spider's eye, an image in one color will not come to the same focus as an image in another color. That allows the spider to gauge distance by changing the focus of the eye, determining range by the shifting back and forth of the focus from one retinal layer to another. Obviously, the spider has a certain amount of hardwired brain power to allow it to automatically perform this calculation.

* An article by Carl Zimmer for THE NEW YORK TIMES ("Tipsy Fruit Flies On A Mission", 16 February 2012) talked about, of all things, drunken fruitflies. It's more interesting than it sounds. Fruit flies like to lay eggs in overripe fruit, the maggots hatching to feed on the yeast and bacteria growing on the fruit. The maggots in turn are targeted by parasitic wasps, which lay their own eggs on the maggots; the wasp eggs hatch, with the wasp larva then literally eating their hosts alive. However, fermented fruit has a tendency to produce alcohol, sometime to the level of proof of a bottle of beer -- and while alcohol can be toxic to small creatures, fruit flies have acquired a taste for it. It turns out that parasitic wasps tend to be poisoned by alcohol, and so it's an effective countermeasure against the parasites.

This finding was the result of a study of the common fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster conducted by a group under biologist Todd Schlenke of Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. The fruitflies have enzymes to neutralize the toxic effects of alcohol, but the wasps remain vulnerable to it. The study investigated a group of fly maggots whose diet had included about 6% ethanol and a control group that got no ethanol; the wasps laid 60% fewer eggs on the "drunks" than on the control group. Even those "drunks" that had been parasitized by wasp larva were protected, with 65% of the wasp larva dying by ejecting their guts out the anus.

Further studies showed that the flies tended to seek out food loaded with alcohol. However, as tends to happen in evolution, the wasps were just a step behind. Tests with a wasp that specializes in parasitizing D. melanogaster showed that its larva were much less vulnerable to alcohol than generalist wasps that also targeted the fruitflies, with only 10% of the specialist larva dying. Says Schlenke: "The wasps are tracking their hosts over evolutionary time."

* Every now and then I run into a "hoverfly", a beast that's clearly a fly but has yellowjacket coloration -- they have an odd tendency to come up to my face, hover in front of me for a moment as if trying to figure out what I am, and then zip off. Obviously the yellowjacket coloration is protective mimicry, intended to warn off predators that they might get stung -- even though they won't. It works on me, I'm not inclined to find out if hoverflies can bite or not. They're generally harmless, many species being pollinators, hoverflies sometimes being called "flower flies", some species preying on aphids and other plant pests.

There's an inclination to marvel at the convincing camouflage of mimics, but we tend to have a selection effect in our consideration, overlooking species that aren't so marvelous. A group of Canadian researchers at Carleton University in Ottawa got to investigating hoverfly mimicry, and observed that some hoverflies are very crude mimics compared to others. That might seem to be a little puzzling under evolutionary terms, since the poorer mimics should be more heavily targeted by predators than the better mimics, eventually putting the poorer mimics out of business.

The group performed a careful analysis of 81 hoverfly species and found that the accuracy of the mimicry was proportional to the size of the hoverfly. Smaller hoverflies, being harder to see, didn't need the same level of camouflage, and they also weren't as tempting targets as the bigger hoverflies. It makes perfect sense, evolution not being about "survival of the fittest" but about "survival of the fit enough" -- once the smaller hoverflies acquired enough of a resemblance to a yellowjacket to discourage predators, any further improvement in the resemblance didn't yield enough additional discouragement, and so there was no winnowing-out of small species to that end.

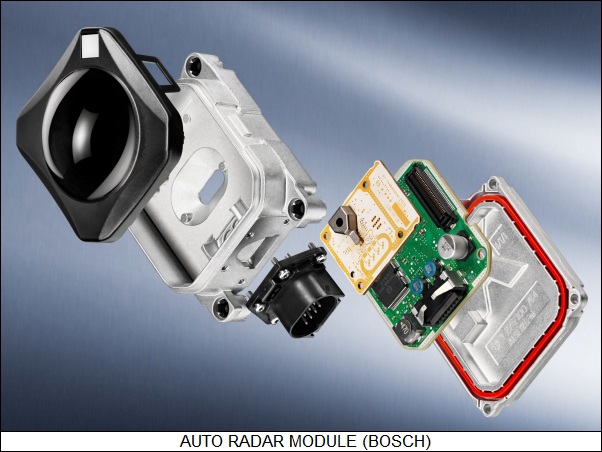

COMMENT ON ARTICLE* AUTO RADARS EXAMINED: As discussed in an article from IEEE SPECTRUM ("Long-Distance Car Radar" by Richard Stevenson, October 2011), the first commercial car radar systems appeared in Japan, on the Toyota Celsior, in 1997. Today, radar is a popular option for high-end autos, adding about $1,000 USD to the pricetag. The market has been expanding at about 40% a year, and as prices fall, that rate should rise. Radar sounds like a silly gimmick, high-tech fuzzy dice, but those who drive radar-equipped cars tend to swear by the technology. In itself it may be only a gadget, but coupled with "smart" collision-avoidance systems it can be a life-saver.

One of the first experimental car radars was developed in the late 1960s by Mullard Research Laboratories in the UK, with the device operating at 10 gigahertz (GHz); RCA followed in 1972 with a system operating in the same band. One of the big problems with the relatively low frequency was that it meant big and bulky antennas, and so in the course of continued development the frequency was raised, first to 34 GHz, then to 50 GHz, and finally to 77 GHz. The choice of frequency has something to do with the absorption of microwaves in the air and a lot to do with legislation, the law placing strict limits on power for the lower frequencies -- which is why systems in the lower bands have a range of only a few meters, just enough to avoid fender benders in stop-and-go traffic.

For the higher frequencies, until recently long-range auto radars have been dependent on fast gallium arsenide chips, which tend towards the expensive. In 2009, the German chipmaker Infineon Technologies, based in Neubiberg, introduced a single silicon-based chip for driving a radar system. Then Infineon teamed up with Bosch and started supplying a more flexible, two-chip variant for radar systems in 2010 models of the Audi A8, Porsche Panamera, and Volkswagen Touareg. Not only are these new systems cheaper than previous car radars, they also have significantly better performance, covering more than four times the area in front of the car four times as accurately.

Silicon is expected to quickly displace gallium arsenide in car radars and many other high-frequency applications. Few expected that silicon could be fast enough to keep up with gallium arsenide, but Infineon engineers came up with a trick, inserting into the core of the device a thin layer of four parts silicon and one part germanium. The idea wasn't really all that new, having been conceived in the 1950s, with experimental devices developed from the 1970s. Adding the layer of silicon germanium alloy introduces electric fields that present the moving electron with the equivalent of a downhill path, speeding it up.

The new transistor configuration also results in lower noise. The speed of conventional silicon transistors can be increased by using a thinner base layer, but that tends to increase resistance and noise. The resistance of the base layer can be reduced by heavily doping it with boron to introduce more "holes", increasing charge carrier flow -- but at the expense of transistor amplification, or "gain". Adding the silicon germanium layer gets around the obstacles, boosting the gain, while permitting heavy base doping to reduce resistance.

Infineon first developed such transistors in the early 1990s, but had problems finding a market for them, until the company focused on auto radar. In 2004, Infineon began a three-year automotive radar program using subsidies from the German government. The project involved Infineon in collaboration with automotive radar system makers Bosch and Continental, and carmakers BMW and Daimler. Early prototypes couldn't operate at the required 77 GHz, but by 2007 Infineon's process improvements had led to devices that could do the job.

The Infineon chips are now in commercial volume production and require no particularly exotic production steps. They are not only cheaper but, as mentioned, more capable than the gallium arsenide competition. When Bosch integrated leading-edge Infineon chips into a third-generation Bosch radar, minimum range was cut by a factor of four, maximum range increased by two-thirds, the detection angle doubled, while the accuracy of angle and distance measurements increased fourfold.

The core module of the Bosch radar is smaller than a pack of cigarettes. The system uses four antennas and a big plastic lens to fire microwaves forward and detect the echoes. It isn't a pulsed radar, instead operating as "frequency modulated continuous wave (FM-CW)" system, ramping up and down continuously in frequency over a 500 megahertz bandwidth around the 77 GHz band. FM-CW is a common scheme in ranging radars; interference between two radars is unlikely because the probability of two radars ramping up and down in step is very small. The system compares the amplitudes and phases of the echoes, pinpointing each car to within 10 centimeters (4 inches) in distance and 0.1 degree in displacement from the axis of motion. It then works out which cars are getting closer or farther away by using the "Doppler shift", the change in frequency of a signal due to the motion of the target. The radar can track 33 objects at a time. There was no radar on the planet that sophisticated a half-century ago.

On the Audi A8, a driver gets two warnings when the car gets too close to the one in front of it: first, a high-pitched alarm sounds and a light appears on the dashboard. If that doesn't get the driver's attention, then the car automatically "taps on the brakes" as a stronger hint, with trials showing that to be very effective. While drivers don't always step on the brakes hard enough to prevent a collision, the Audi A8 will enhance the braking automatically. If a collision is absolutely unavoidable, the Audi A8 will take over the brakes completely.

Drivers rarely encounter such drastic situations, so for the most part the perceived value of radar is in enhanced cruise control. A driver can set the radar to lock onto the vehicle in front and keep pace with it, braking and speeding up appropriately. The driver specifies the following distance and the maximum allowable speed, which can be as high as 250 kilometers per hour (155 miles per hour). Auto radar certainly doesn't allow a car to drive itself -- but when the day comes when cars can do so, radar technology to support them will be available.

COMMENT ON ARTICLE* REGULATORY QUANDARY: It is commonly said there are two certainties, death and taxes, to which one might add a third: bureaucracy. No matter how much people complain about it, bureaucracy never goes away, though the complaints do drop a hint to the people in charge that something should be done to restrain it -- placing governments in the awkward position of trying to control the system the governments have created.

As reported by THE ECONOMIST ("Of Sunstein & Sunsets", 18 February 2012), in 1980 the US government set up an "Office Of Information & Regulatory Affairs (OIRA)" within the Office of Management & Budget to exert some oversight on regulations. US President Barack Obama has now hired Cass Sunstein, a University of Chicago legal scholar, to head the OIRA. Sunstein is highly respected for his innovative approach to regulatory issues, favoring a "libertarian paternalism" -- a contrary-sounding phrase that equates to encouraging instead of coercing citizens to do the right thing. Sunstein has been involved in redesigning dietary recommendations and fuel-efficiency stickers for cars, making formerly confusing information more useful.

Sunstein is now responsible for implementing a 2011 executive order issued by Obama to tell the agencies under White House control to trim down their rule books. Sunstein says all have complied, providing him with 580 suggestions, adding that the agencies have demonstrated considerable enthusiasm for the task. It seems the people who administer the rules can find them a pain.

However, to no surprise the Obama Administration has continued to pile up rules at a painful rate. Even if most the rules have more benefits than costs, as the agencies like to claim, the end result is an expansion of the regulatory web -- whose total cost is unknown, with no impartial way of measuring it. Agencies cook up their own numbers to show a benefit; critics fire back negative studies to show a burden. All acknowledge that meeting regulations requires work, and the more regulations, the more work.

Once regulations are in place, they're hard to get rid of. Each removal must go through the same cumbersome process it took to put the regulation in place -- comment periods, internal reviews, and constant lobbying. Ironically, regulated industries may actually not want regulations removed; they've taken the financial hit on compliance, and don't want their competitors to get away with dodging the bullet. Proposals have been floated to make it easier to kill off regulations:

And then there's the REINS bill, which would require that the executive branch obtain congressional approval for the implementation of any new major regulations. It's been passed the Republican-controlled House but unlikely to pass the Democrat-controlled Senate, and Obama has threatened to veto it. The White House doesn't like it, and with good reason, since it would put a Congressional noose around the neck of the executive branch -- along the lines of the infamous "Neutrality Acts" that did so much to tie the hands of Franklin Roosevelt's administration in the lead-up to American intervention in World War II.

Congress is not, is not supposed to be, an administrative organization; that's what the executive branch is for. Congress can introduce bills and grant approval to the actions of the executive branch, but it is simply not set up to actually run anything. A 1999 study showed that a hefty proportion of the US regulatory burden was due to clumsily-written laws passed by Congress. Jim Cooper, a Democratic House member from Tennessee, says that his colleagues "vote on things they have not read, do not have the time to read, and cannot read."

Cooper also points out that Congress is far more under the influence of special interests than the executive branch: "There is a pimento lobby. You do not want to cross the pimento people." A bureaucracy is difficult enough; a bureaucracy under the thumb of "fractious by design" body such as Congress, where nobody is or even should be clearly in charge, would be a nightmare we don't need.

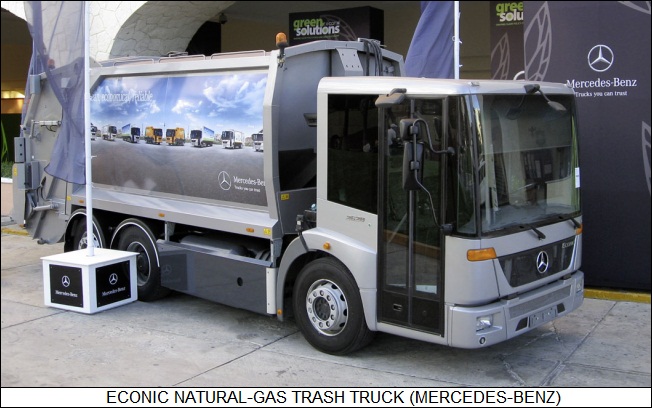

COMMENT ON ARTICLE* NATURAL GAS REVOLUTION (4): As discussed in an article from THE ECONOMIST's tech blogger, Babbbage ("Meet The Meth Drinkers", 9 March 2012), the natural gas revolution also has the prospect of affecting how we drive. The direction of fuel prices at the pump has been, on the average, persistently upward for over a decade now, and nobody expects anything different in the future. Talk of biofuels has become a bit exasperating; some call them a bust, which is a bit extreme, but even advocates have to admit that there's no prospect of biofuels changing America's transport equation any time soon.