* 23 entries including: once & future Earth (series), understanding AI (series), China's environmental push, supersonic transport activity, improving Africa's crops, using rabies to treat brain cancer, human bacteriophage phageome, animals with no intestinal microbiome, making robocars smarter, GRB capture by gravity-wave observatories, and using the microbiome for medicinal purposes.

* NEWS COMMENTARY FOR JANUARY 2018: As discussed by an essay from REUTERS.com ("Inside The Growing Backlash Against China" by Peter Marino, 10 January 2018), the current paralysis of the USA as the pre-eminent world power has done much to elevate the stature of China -- seen until recently as the second-rank power, though now the relative status of the two nations is open to argument.

There is no argument that China's rise to global prominence has been breathtaking. Centuries ago, China was the greatest nation on Earth; it then fell into a long era of decay. It wasn't until a generation ago that China began its rapid ascent, and now it stands astride the world. However, the traditional policy of modern China was to keep a low profile in international affairs. Under President Xi Jinping, that's now changing -- one of the consequences being a growing backlash against China. Countries that only a few years ago welcomed Chinese investment and engagement are becoming wary.

The rise of China was enabled by the end of the Cold War. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the West in general and the United States in particular were eager to bring more countries into the postwar world order they had created. The USA in particular pushed for China's hook-up with the World Trade Organization (WTO), which marked the coming of age of China as an international economic power. Faith in the liberalizing power of commerce was very strong in that era, with concerns over China's autocratic governance put on the back burner. In time, the perception was, China might well liberalize and become another multiparty democracy.

Nonetheless, to most of the world, China was a secondary issue. The US became strategically focused on Islamic terrorism, the Middle East, and Afghanistan, while Europe's primary focus was on the European Union. Only Japan, among the major democracies, maintained a continuous strategic focus on its Chinese neighbor.

In the meantime, Beijing kept a low profile. At the outset of China's economic reform project Deng Xiaoping, the leader of China up to his death in 1997, encouraged the ruling elite to keep a low international profile. Deng's slogan was "taoguang yanghui" -- literally "Hide Brightness, Cultivate Obscurity," but generally translated in English as: "Lay Low and Bide Your Time". What he meant was that China shouldn't try to throw its weight around, until the country could actually back it up.

China worked on the basis of discreet diplomacy, with a focus on "win-win" cooperation, to help make friends. At the United Nations, Chinese diplomats generally let Russia to take the lead in diplomatic confrontations with the West. The global backlash against the Iraq war gave Beijing an opportunity to promote itself, even launching the China-Europe Strategic Partnership in 2003, allegedly to create an alternative to American unipolar power.

The creation of the BRIC Forum for emerging economies in 2009 extended the image of "China the Reliable Partner" to developing countries outside the West. Throughout this period, even as China grew more powerful, Chinese leadership played the cards close to the vest, damping suspicions in partner countries. From Australian mines to Confucius institutes in Western universities, China continued to extend its influence.

In the course of the current decade, taoguang yanghui has been set aside. Discreet diplomacy has given way to grand proposals; strategic ambiguity has disappeared as China sought foreign military bases, conducted high-profile military training exercises, presented shows of armed might in parades, and engaged in confrontations with neighbors.

Fueled by big state-subsidized loans, large Chinese firms were sent on international buying sprees, scooping up the Waldorf Astoria in New York City and a number of well-known brands such as GE and Volvo -- leading to fears among Western legislators that such acquisitions might give the Chinese government influence over crucial commercial assets. The growing Chinese presence in Africa has led to worries that that China's investments on the continent are less about partnership and investment than they are about domineering Chinese political influence, and neo-colonial policies, in resource-rich countries.

After solidifying his control over the Chinese Communist Party in late 2017, Xi is pressing on. The Communist Party's United Work Front division has begun to enforce guidelines on the behavior of Chinese university students studying overseas. Chinese academics have drawn the wrath of the Ministry of Education for failing to toe the Party line. The state has come down hard on dissidents.

The most visible of Xi's actions on the international stage is the "One Belt, One Road" initiative -- a broad program for spending hundreds of billions to build up international infrastructure. It sounds good on paper; but there's the question of implementation, with China recently seizing ownership of a port in Sri Lanka after local entities defaulted on the onerous terms that China had demanded. There were loud protests in Sri Lanka, leading other countries to wonder what strings might be attached to Chinese investment.

Mao Zedong's China presented itself as an adversary of "Western imperialism". Under Xi, the image has flipped over, with a China in the self-conscious image of a great power that can state its own terms. Such nationalism goes over well with the Chinese people, not so well elsewhere. Donald Trump's snipings at China over trade have a hollow feel; but the tensions are real enough, the Pentagon having officially described China, along with Russia, as America's primary adversaries. Canada and Australia are becoming similarly cautious.

Pakistan, a traditional ally of China and part of the One Belt, One Road program, has reportedly been stiffed by China, Beijing said to have abruptly stopped funding for three major Pakistani roads in the project known as the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Outspoken French President Emmanuel Macron publicly declared that the Belt & Road projects "cannot be those of a new hegemony, which would transform those that they cross into vassals."

China has long faced suspicion from the West -- it was much worse in Mao's day -- but now also faces suspicion in the developing world. Modern Chinese diplomats have reinvented taoguang yanghui into dodging criticisms, while remaining opaque about China's intent. That leaves nothing but the principle of "watch what I do, ignore what I say" -- which means the suspicion is inevitably going to intensify.

* As discussed by an article from ECONOMIST.com ("America INC Gets Woke", 30 November 2017), at the start of Donald Trump's presidency, company bosses rushed onto his business councils, expecting to influence policies in their favor. Their enthusiasm faded when Trump banned travel from Muslim-majority countries; withdrew from the Paris agreement on climate change; and waffled on racist protesters in Charlottesville. In the case of the last, Trump's business council simply evaporated in the face of resignations.

Reed Hastings, Netflix's boss, called the immigration ban "un-American", while Sergey Brin, co-founder of Google, attended a San Francisco protest against the ban, telling a reporter: "I am here because I am a refugee." Other executives have signed up with lawsuits to overturn Trump's policies, and publicly condemned his actions.

It's nothing new for companies to be drawn into social and political debates. For example, anti-apartheid campaigners mounted boycotts against firms that did business with the South African regime, for example. However, now it's a new normal. In 2015, Indiana considered a "religious freedom" bill that would allow companies and non-profit organizations to discriminate against gay and transgender individuals. Tim Cook, chief executive of Apple, blasted the proposal, even though Apple itself has little presence in the state. State bills discriminating against LGBT people have attracted strong opposition from firms headquartered across America, not just in Left-leaning California -- from Bank of America, in North Carolina; to Dow Chemical, in Michigan; and ExxonMobil, in Texas.

Trump's inflammatory actions have driven the politicization. More than 1,400 companies and investors signed a pledge to uphold the Paris climate agreement. One serial investor and director of a tech giant says that angry employees have made it very hard to be seen as co-operating with the Trump Administration in any way.

Traditionally, companies tried to be apolitical, focusing on business, the intent being to avoid alienating customers and confrontations with the authorities. No longer. Multinational companies in particular are more likely to combine their support for globalization with advocacy of social goals such as protecting the environment, ethnic diversity, and gay rights. Indeed, a small but growing number of firms have committed to a new corporate vision, declaring their objectives to be broader than mere profits. The past decade has seen the launch of "benefit corporations" that work towards specific goals for society as well as for their investors. There are more than 2,300 of such around the world, the majority in the USA.

Such trends are seen elsewhere. Companies in Europe have long had an strong view of their social responsibilities, with worries over inequality and the resulting populist backlash are strengthening their commitment. For example Unilever, the Anglo-Dutch consumer goods giant, prides itself on paternalistic treatment of staff well supporting environmental sustainability. However, the phenomenon is particularly noticeable in the USA -- not just because of the many giant firms headquartered there, but because Trump's presidency has done so much to raise the level of social agitation.

The bosses of the companies are being pushed by their young employees, the majority of which find Trump appalling, and by investors, who don't generally think much more of Trump themselves. The pressure is predominantly from the Left -- one reason being that many of America's biggest companies have their headquarters in states and in metropolitan areas that voted for Hillary Clinton. Staying neutral is especially tough for firms in Silicon Valley, where staff are often liberal. If the bosses are forced to take a stand, they also will do so as per their own inclinations: it was no great surprise that Tim Cook spoke out against "religious freedom" bills, since Cook is gay.

However, the corporate shift is not restricted to the trendy coastal regions. Retail giant Walmart, headquartered in Arkansas, opposed a "religious freedom" bill in that state; the company has similarly stopped selling products featuring the Confederate battle flag, and also stopped peddling assault weapons. To be sure, there are companies that lean to the Right. Charles Koch of Koch Industries, the second-largest private firm in America, for example, has spent hundreds of millions backing Rightist causes.

It is significant that the Koch Industries is a private firm; corporations do not follow the example of the notorious "Kochtopus". There are a few companies, like Hobby Lobby, a chain of crafts stores, that have pushed back from the Right, but they are heavily outnumbered. The big oil companies seem conflicted -- sometimes trying to push back on climate change awareness, sometimes trying to ignore it, only hesitantly trying to come to grips with the inevitable.

In the face of the pressure towards social activism, companies end up walking a fine line. One problem is doing too little, to be accused of purely cosmetic efforts. They're under scrutiny by independent monitors such as the Human Rights Campaign, which inspects how firms treat gay and transgender employees; or the World Wildlife Fund, which tracks firms' environmental work. On the other hand, any actions the firms take lead to the complementary problem of antagonizing the other side. No matter what a company does, somebody's going to be offended.

That being the case, the bosses end up considering the direction of the prevailing wind, and it's from the Left. Drawing the wrath of Trump can be troublesome -- but being agreeable with him can be troublesome as well. Complaints from the Right simply don't carry much weight.

The pressure on corporations to stand up for what's right is expanding in scope. Companies are being taken to task for their (legal) tax-avoidance efforts; for sky-high executive pay; for automating their factories and laying off workers. They are being driven to contribute to political campaigns -- thanks to the Supreme Court's decision in CITIZENS UNITED V FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION that businesses can spend as much as they like in elections, as long as they do not donate directly to a candidate.

That isn't much of a restriction, the mechanisms for staying out of trouble with campaign donations being well-understood. Ironically, the Left calls out politicians for being in the pockets of rich donors; but it could be equally seen as politicians shaking down donors. In the face of notorious Kochtopus and its funding of Right-wing causes, the Left is not in a good position to complain about corporate donations supporting Left-wing political action. The bosses really don't need to worry much about the extreme Left, since few employees and investors are anti-capitalist.

Companies like Apple, Google, and Amazon already do a good deal of political lobbying -- but to date, it's mostly been for matters of importance to them, such as net neutrality, intellectual property, and privacy. They're under pressure to do more, with the activism of firms against Trump's withdrawal from the Paris climate agreement showing the pressure is having an effect.

Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg, suspected of presidential aspirations, recently conducted a tour of 30 states to try and connect with Americans of all backgrounds. In the 1830s, the French scholar Alexis de Tocqueville conducted a tour of the USA, making astute observations of the conduct of Americans, notably commenting on their "self-interest, properly understood" -- that is, their idea that what was good for the collective was, as a strong rule, good for the individual members of the collective.

That's a notion entirely out of odds with the spirit of Trumpism: "Hang the public interest, cut my taxes!" That mindset has led to a backlash, with companies forced to give up straddling the fence politically -- to embrace the reality that the public interest, like it or not, has become tightly coupled to their own interests.

* While the news, particularly these days, tends toward the discouraging, an essay from TIME.com by billionaire Warren Buffett ("Warren Buffett Shares the Secrets To Wealth In America", 4 January 2018), made a case for optimism -- saying that, despite the current despair, the next generation of Americans will be economically better off than their parents.

How can that be? It seems the boom times are over; even though the economy has recovered, it's only achieving growth at a rate of an anemic 2% a year as of late. Buffett says not to worry:

BEGIN QUOTE:

Before we shed tears over that figure, let's do a little math, recognizing that GDP per capita is what counts. If, for example, the US population were to grow 3% annually while GDP grew 2%, prospects would indeed be bleak for our children. But that's not the case. We can be confident that births minus deaths will add no more than 0.5% yearly to America's population. Immigration is more difficult to predict. I believe 1 million people annually is a reasonable estimate, an influx that will add 0.3% annually to population growth.

In total, therefore, you can expect America's population to increase about 0.8% a year. Under that assumption, gains of 2% in real GDP -- that is, without nominal gains produced by inflation-will annually deliver 1.2% growth in per capita GDP. This pace no doubt sounds paltry. But over time, it works wonders. In 25 years -- a single generation -- 1.2% annual growth boosts our current $59,000 of GDP per capita to $79,000. This $20,000 increase guarantees a far better life for our children.

END QUOTE

Buffett sees that past American experience gives good reason to see this future as perfectly realistic. Today, as he points out, a prosperous family has options for travel, entertainment, medicine, and education that were not available to the filthy rich of his childhood in the 1930s. All through American history, innovation and corresponding improvements in productivity have revolutionized the US economy. In the early days of the republic, about 80% of the workforce labored on farms; today, the headcount is only 2%, and those farms are vastly more productive thanks to new technology.

The shift from farms to industry meant a great increase in prosperity. It also meant an almost complete displacement of the labor force from agriculture to industry. That was troublesome, but it took place over a long period of time. Now the revolutionary cycle has accelerated -- implying a further increase in prosperity:

BEGIN QUOTE:

Let's think again about 1930. Imagine someone then predicting that real per capita GDP would increase sixfold during my lifetime. My parents would have immediately dismissed such a gain as impossible. If somehow, though, they could have imagined it actually transpiring, they would concurrently have predicted something close to universal prosperity.

END QUOTE

Alas, there are downsides, the first being the inevitable turmoil in the destruction of old jobs and the creation of new jobs. The second is that growth isn't leading to universal prosperity, but an accumulation of wealth in the upper-income half of the population, with a stratospheric concentration in the top few percent -- while millions of citizens in the lower half remained stuck on an economic treadmill. The optimistic slogan of "trickle-down" economics proved false, as if it were any surprise to the alert. Instead, money flowed upward, even as the drive for ending all government regulation of the market system grew ever louder:

BEGIN QUOTE:

The market system, however, has also left many people hopelessly behind, particularly as it has become ever more specialized. These devastating side effects can be ameliorated: a rich family takes care of all its children, not just those with talents valued by the marketplace. In the years of growth that certainly lie ahead, I have no doubt that America can both deliver riches to many and a decent life to all. We must not settle for less.

END QUOTE

BACK_TO_TOP* GREEN CHINA? As discussed by an article from ECONOMIST.com ("As China Gets Tough On Pollution, Will Its Economy Suffer?", 5 January 2018), China's environment ministry used to be toothless, Chinese using the phrase "loud thunder, little rain" -- much like "all bark, no bite" -- to describe the behavior of ministry officials. They would give warnings to polluters to clean up; then hand them a trivial fine if they didn't.

The government in Beijing has long spoken of going green, but was lazy in moving against polluters, lest it cost Chinese citizens their jobs. The government, however, is not democratic; and once committed to the necessity of action, may act ruthlessly. During the course of 2017, policies changed, with the environment ministry moving on coalminers, cement-makers, paper mills, chemical factories, textile firms, and others.

Tens of thousands of companies, typically small ones, have been shut down. In the region around Beijing this winter, the government ordered steel mills to run at half-capacity, and aluminum-makers to cut output by nearly a third. Enforcement has shifted from weak to overbearing. In the northern province of Hebei, a ban on coal heating left thousands of residents shivering because the replacement, a switch to natural gas, wasn't ready.

The question is: how much will the crackdown cost China, and the global economy? Shouldn't such severe measures hurt growth -- as well as boost inflation, as production cuts force up prices? Jiang Chao, an economist at Haitong Securities, a broker, suggests it might lead to "classic stagflation" -- the perverse situation in which prices inflate, even as the economy stagnates. The reality is that growth has continued, and inflation has stayed tame. Maybe the pollution controls take time to bite? Or is it possible, just possible, that China will be able to raise its environmental standards, without suffering an economic penalty?

The government feels compelled to act, the authorities having acknowledged that pollution is a serious problem. The air in China's cities tends towards the brutally foul, with citizens of Beijing suffering bad health effects comparable to smoking a pack of cigarettes a day, or more. The Chinese Communist Party sees tackling pollution as absolutely essential in maintaining the authority of its rule with Chinese citizens.

True, some of the measures, like those to clean up Beijing's air this winter, are short-term efforts; but others are for the long haul. As part of a "war on pollution" declared in 2014, China has detailed targets for cleaning up its air, water, and soil. On 1 January 2018, a new environmental-protection tax went into a effect, to replace a patchwork of pollution fees. In the previous month of December 2017, China launched an emissions-trading market scheme; it was scaled back from what was originally planned, it is still the world's biggest. In July, China banned imports of 24 kinds of waste such as paper and plastic; the ban came fully into effect on 1 January.

The most significant aspect of the new order, however, is the empowerment of the environment ministry. Besides fining companies, inspectors have disciplined some 18,000 government officials for failing to act against pollution; officials now know that environmental awareness is on their report card. Only 60% of steel blast furnaces are now in use. Some manufacturers are worried about obtaining parts, or that they will have to relocate.

There have been surges in coal and steel prices, as well as prices for paper, some chemicals, and rare-earth metals. Overall, however, there hasn't been significant weakening in production, which is still growing at 6% a year. There hasn't been much inflation, either. Is the thriving economy simply rolling on from momentum, to presently start running down? There are three reasons to think it's going to keep on rolling:

On the balance, it seems the puzzle is not that China's pollution crackdown has proven so benign in practice; the puzzle is that it took so long to take action. That's not so hard to understand, given China's polluting smokestack industries are concentrated in a few provinces, such as Shandong in the east and Shanxi in the north. Local officials didn't want to upset the economic order in their provinces; once the central government took charge, it could override regional hesitations.

At a time when the United States seems, at least in the White House, to be in retreat from environmental action, China is demonstrating long-term vision, backed up by tough measures. The irony is that America, suffering under delusions of short-term thinking, is likely to end up with less of a payoff than China.

COMMENT ON ARTICLE* UNDERSTANDING AI (9): Users of Google's Android Assistant like to test the system, for example often asking: "Will you marry me?" Of course, that's just clowning around; when handed a conversational system, users like to see what kind of answers they get to off-the-wall questions. A2 plays along with the gag, replying: "I'm flattered that you're looking for commitment."

In other cases, it's not so easy to determine where a user's question is coming from. The job of doing so on the personality team falls to the "empathic designer", Danielle Krettek. Krettek is lively, outgoing, and highly interactive in her demeanor, with social skills that carry seamlessly into her work. For example, suppose a user tells A2: "I'm stressed out." A2 replies: "You must have a ton on your mind. How can I help?"

That is a carefully limited answer, one aspect being that it compels the user to think of what help A2 can, and cannot, provide. Nonetheless, as Krettek says: "That acknowledgment makes people feel seen and heard. It's the equivalent of eye contact."

The personality team gets inspiration in its work from all over. According to Coats and Germick, improvisational comedy has been a particularly significant influence. That's because dialogue in "improv" is like a session in verbal juggling between the participants, one tossing out a line, the other picking it up and throwing it back -- a process known as "yes-and". According to Germick, most of the people on the personality team have done improv at some time in their careers.

You'll get an example of the "yes-and" principle at work if you ask A2 about its favorite flavor of ice cream. "We wouldn't say: 'I do not eat ice cream, I do not have a body,'" explains Germick. "We also wouldn't say: 'I love chocolate ice cream and I eat it every Tuesday with my sister.' -- because that also is not true." In these situations, the writers look for general answers that invite the user to keep talking. Google responds to the ice cream question, for instance, by saying something like: "You can't go wrong with Neapolitan, there's something for everyone."

However, ask it about a specific flavor within Neapolitan, like vanilla or strawberry, and it's at a loss. That's not such a problem; nobody's going to ask such questions unless they're playing "stump the machine", and they'll run into a dead end sooner or later at that game. However, A2 also struggles with some of the basics of conversation, such as interpreting certain requests that are phrased differently from the questions it's programmed to understand. It also doesn't know how to read tone of voice, much less facial expressions -- not that users, when talking to a smartphone or smart speaker, expect them to.

A2 does track user history to learn what a user is most likely after, and to avoid sounding repetitive. Germick believes that history can be exploited much further:

BEGIN QUOTE:

We're not totally there yet. But we'd be able to start to understand, is this a user that likes to joke around more, or is this a user that's more about business? The holy grail to me is that we can really understand human language to a point where almost anything I can say will be understood -- even if there's an emotional subtext or some sort of idiom.

END QUOTE

At present, the team is focusing on nuances of speech. When A2 reports on the weather, it may emphasize words like "mostly"; and its voice sounds slightly higher when it says "no" at the start of a sentence. These subtleties were wired in by James Giangola, an expert in linguistics and prosody -- the second being the study of patterns of stress and intonation in language. He's the team's conversation and persona design lead. Giangola is a believer in "voice user interfaces" -- VUI, spoken as "vooey" -- since, as he says, "voice is such a personal marker of social identity." He elaborates: "Voice is your place in society."

All the subtleties aside, VUI has some major obstacles to overcome. First is that the majority of users don't use voice often, not finding it convenient, or at all -- a problem aggravated by the immaturity of the technology, since it doesn't work well enough to be convenient. Privacy is another issue: if A2 is listening to a user all the time, everything that user says might end up as damaging evidence in a court of law.

Germick is perfectly aware of A2's limitations, but he's not discouraged, seeing the personality team's efforts as an exploration of a new frontier. As Oren Etzioni -- CEO of the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence in Seattle -- put it, VUI offers "a completely different level of interaction. This really becomes a game changer when you can have a dialogue with a virtual assistant that may be at the level of a concierge at a hotel." [TO BE CONTINUED]

START | PREV | NEXT | COMMENT ON ARTICLE* ONCE & FUTURE EARTH (23): As far as climate sensitivity goes, theory backed up by lab studies on the absorption of infrared by CO2 suggests that, on its own, a doubling of CO2 concentration would add 1 degree Celsius to the global temperature. Current projections show that CO2 concentrations will double from the pre-industrial level of 280 PPM to 560 PPM by 2070. Notice the changes involve doubling: it would require raising concentrations to 1,160 PPM to raise temperatures another degree Celsius.

On the face of it, a 1 degree Celsius change hardly seems worth making a fuss about. However, climate is complicated, and increasing CO2 has complicated effects -- particularly in terms of increasing the average concentration of water vapor, with its potential positive and negative feedback effects. The current consensus is that, overall, water vapor provides positive feedback, and that theory says a doubling of CO2 concentration will produce a rise in temperature of 1.7 degrees Celsius.

Everyone also admits that the climate scenarios are complicated and the data is difficult to handle. Researchers are stuck with wading through the bog, and have turned to computer modeling to see if they can make things clear. There are two classes of climate modeling:

EBMs are simpler, but somewhat ad-hoc. GCMs are more difficult to implement, since they involve vast numbers of cells and require considerable computer power; in fact, given current computer hardware, it's out of the question to build a global model with cells approaching, say, a kilometer on a side, since the computing requirements would go through the roof and climb towards the Moon. However, GCMs are regarded as more robust, since they are rooted in basic climate physics.

Both types of models are good enough to accurately simulate features of the real-world climate system, such as monsoons, trade winds, and seasons. They also have the interesting feature that all of them predict global warming -- EBMs less so than GCMs -- and in fact, they tend to predict more warming than could be accounted for by simple theoretical considerations of the effects of CO2 and water vapor, the most extreme prediction being a drastic increase of 4.4 degrees Celsius.

The models also demonstrate that climate sensitivity is dependent on concentration of aerosol particles; the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines in 1991 dumped a layer of sunlight-diffusing sulfur particles into the stratosphere, leading to a temporary cooling that fits with the models as well. There is an ambiguity involved -- some aerosol particles are reflective and provide a cooling effect, others such as soot absorb sunlight and provide a heating effect. The models do seem to track the response of climate to aerosol concentrations over the 20th century fairly well; some climate researchers believe that the recent leveling-off of warming may be at least partly due to an usually high degree of volcanic activity in the corresponding time period.

Incidentally, there is a push to reduce global atmospheric soot concentrations, in particular by replacing inefficient cookstoves in developing countries with new stove designs providing more efficient combustion, the belief being that a dramatic reduction in soot would delay the onset of warming. This effort is aided by the fact that soot is also a health problem, and users would benefit from cleaner-burning stoves anyway.

Data available on what seems to have happened in the prehistoric past also suggest the sensitivity of the models is realistic. During the Ice Ages, the expanded polar icecaps did increase the reflectivity of the Earth, contributing to cooling, but studies show they couldn't have kept the Earth cool on their own. The Earth also had relatively low CO2 concentrations, and factoring in high sensitivity gives a reasonable fit to the known global temperatures. Before the Ice Ages, the Earth had slightly higher CO2 concentrations than today but was a good deal warmer, again suggesting sensitivity. [TO BE CONTINUED]

START | PREV | NEXT | COMMENT ON ARTICLE* WINGS & WEAPONS: As discussed by an article from JANES.com ("Patria NEMO Container Completes Land Test Firings" by Charles Forrester, 15 September 2017), there's been a push towards modular weapon systems -- as demonstrated by the NEMO 120-millimeter mortar system developed by Patria of Finland, which built around a standard 6-meter (20-foot) shipping container. NEMO is being developed in cooperation with the UAE Navy. Being based on a shipping container, it can be hauled, and as a rule fired, by any transport system that can handle such a container. Although NEMO was designed for use on warships, it was test-fired from an 8x8 cargo truck.

The system weighs 10 tonnes (10.1 tons) when empty and has the capacity to carry 100 mortar bombs. It is crewed by three - two loaders and a gunner, with the latter doubling as the commander. The mortar can be elevated from -3 to 85 degrees, and is capable of engaging targets as far as 10 kilometers (6 miles) away. It has a rate of fire of up to ten rounds a minute, and is capable of direct or indirect fire. Recoil brakes reduce the shock from firing from 120 tonnes (132 tons) to 20 tonnes (22 tons). Patria will begin deliveries to the UAE Navy in 2018; other nations have expressed interest in the system.

* Future aircraft concepts increasingly envision hybrid propulsion systems, with a gas turbine turning a generator to power electrically-driven fans. As discussed by an article from FLIGHTGLOBAL.com ("GE Reveals Major Achievements In Hybrid Electric Propulsion" by Stephen Trimble, 25 August 2017), engine giant GE Aviation has publicly revealed details of investigations toward powerplants for such hybrid machines.

Competitors Honeywell and Rolls-Royce had previously announced details their work on hybrid propulsion technology. These two companies are collaborating on development of a 1-megawatt (MW) class hybrid propulsion system for the Aurora Flight Sciences XV-24A, a demonstrator drone being developed for the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, discussed here in 2016. GE has more quietly been developing a comparable technology, intended for both military and civil applications.

GE has been working on both powerplants and electric motors. As a demonstration, GE modified an F110 bypass turbojet -- used on the F-15 and F-16 fighters -- to turn out 1 MW of power, with 250 kW from the high-pressure turbine and 750 kW from the low-pressure turbine; obtaining power from both turbines is an innovation. A megawatt of power is equivalent to about 1,340 HP; the F110 of course still generates thrust, the engine being rated up to 142 kN (14,510 kgp / 32,000 lbf), equivalent to about 44,300 HP.

As a standard of reference, the Boeing 787 jetliner uses six generators to produce a maximum load of 1.4 MW of electric power -- which the aircraft uses to provide power for de-icing the wing and engine nacelles, as well as pressurizing the cabin. GE also demonstrated an advanced electric motor driving a propeller made by Dowty, a GE subsidiary. The motor is 98% efficient; GE envisions an all-up 1 MW propulsion system as competitive with the popular Pratt & Whitney PT6A turboprop, but much more efficient, with only a fifth of the waste heat.

Aircraft manufacturers are now considering hybrid aircraft with passenger loads of up to 150 seats. Airbus has a roadmap envisioning a narrowbody-class hybrid airliner in the 2030s, while Boeing has teamed up with JetBlue Technology Ventures to fund Zunum Aero, which is designing a hybrid-electric business aircraft and 50-seat regional jet, to fly in the early 2020s. To meet the emerging market, in 2013 GE opened a $51 million USD Electrical Power Integrated System Center (EpisCenter) in Dayton, Ohio, the facility being set up to test electric power systems ranging in size from 500kW to 2.5MW.

* As discussed by an article from ECONOMIST.com ("How To Build Cheaper Smart Weapons", 25 May 2017), smart guided munitions have increasingly displaced traditional unguided munitions. The ability to precisely target a bomb or a rocket means "more bang for the buck", as well as helping to keep bystanders out of the line of fire. However, although guidance systems have got much cheaper as they have become more common, smart munitions are still more expensive than dumb munitions.

Frank Fresconi -- of the US Army Research Laboratory's Aeromechanics & Flight Control Group, in Maryland -- has an idea for cheaper smart munitions, under the "Collaborative Cooperative Engagement (CCOE)". The concept is that a cluster of munitions could be fired on a target area, with only one having a smart guidance-targeting system. The rest would only have a wireless guidance link, being given course updates by the smart munition. It would assess the target area, assign targets to each of the slave munitions, and direct each to its target.

Fresconi and his team are not working on any specific weapon, instead focusing on the electronics needed to implement the scheme -- which could be implemented in a cluster bomb, a missile with a cluster warhead, or a pack of small guided rockets. Fresconi is focusing on an optical / infrared imaging target seeker, presumably with GPS midcourse guidance, though of course multimode seekers, with laser or microwave radar targeting, are possible. There is a possibility that the wireless link between the munitions could be jammed, but the short range between them should be able to counter jamming to an extent. Preliminary tests have been performed, though Fresconi doesn't see the scheme is ready for fielding just yet.

COMMENT ON ARTICLE* RETURN OF THE SST? As discussed by an article from WIRED.com ("Supersonic Planes Are Mounting a Comeback -- Without That Earth-Shaking Boom" by Eric Adams, 15 March 2017), supersonic transports -- SSTs -- were all the rage in the 1960s. Aircraft speed had been increasing rapidly from World War II, with military aircraft advancing from piston power to Mach 2 jet machines. Airliners had similarly advanced to jetliners, though they remained subsonic; with supersonic military aircraft in widespread service, it seemed perfectly logical to evolve to commercial SSTs.

In hindsight, this vision of an SST future was glib, unrealistic under close examination. Military aircraft had to engage in combat, with the perception that the side with the faster combat aircraft would prevail in a confrontation; commercial aviation had no similar imperative, and was under cost constraints, the advantage being to the airline that could offer the best fares. The perceptive might have noticed that the military did not have and did not want supersonic transport aircraft; it would have made little sense for hauling passengers, and even less sense for hauling cargo. There was also the problem that operating a big supersonic jet over land meant troublesome sonic booms.

In the end, the only SST to be built and reach full commercial service was the Anglo-French Concorde, with only 20 built. By the time it was flying, fuel price had become a concern, and there was no way the Concorde could compete with subsonic jetliners, all the more so because it could only fly over the oceans. In over a quarter-century of operation, it never turned a profit, if development costs were factored in. The Soviets developed their own equivalent, the Tupolev "Tu-144", and withdrew it after a few years of service. Boeing planned a big, impressive "Model 2707" SST, but it never flew.

Over the past decades, many studies have been performed on development of a new SST. The focus has been primarily on small SSTs, sized to fit the market who regard time as more important than money, and are willing to buy the expensive tickets for an SST ride. Another focus has been on reducing the sonic boom, so SSTs can be operated over land. For years, nothing much has happened -- but now the prospects for a new generation of SSTs are looking up.

Big names like Lockheed Martin and startups backed by Airbus and Virgin Galactic are now moving forward on SST development. Samuel Hammond -- a policy analyst at the Niskanen Center in Washington DC, who has conducted studies on the viability of supersonic transportation -- says that the SST "represents a shrinking of the world, just as the transcontinental railroad and subsonic aviation did before it. But it also stands to reverse a four-decade innovation stagnation in aviation."

Hammond research suggests a potential market for 450 SSTs -- assuming the Federal Aviation Administration eases restrictions on overland flights, which account for the bulk of air travel. Economy of operations remains the challenge, but according a paper he wrote: "With lighter materials, more efficient engines, better computer modeling, and more experience, it is more than possible to create an aircraft today that is both faster and more affordable than the Concorde."

Nobody thinks it's simple, however. One big problem is that there are no commercial engines available at present for an SST; another is that the regulatory environment for air transport is very troublesome, possibly too much for a small startup. Partnerships with big aerospace firms help, but a small company partnering with a big one may end up being a small tail on a big dog.

The most prominent technical obstacle remains sonic boom. The Lockheed Martin team developing the "Quiet Supersonic Technology (QST)" x-plane believes improved streamlining will minimize the boom. The idea is to create a sleeker shape that distributes the shockwaves over a broader area, and add lifting surfaces like a canard, stabilator, and T-tail to further minimize impact points between the airframe and the air, creating fewer shockwaves, according to project manager Peter Iosifidis. Ditching the cockpit canopy in favor of an electronic vision system eliminates another boom point. The refined streamlining also improves flight efficiency.

Iosifidis says the QST would cruise at 16,750 meters (55,000 feet) at Mach 1.4 (1,485 KPH / 925 MPH), producing a mild thump on the ground that people might not even notice. NASA has been conducting wind-tunnel tests of models; a flight prototype won't take to the air before 2023.

Spike Aerospace and Aerion Corporation also are testing designs. Both companies are working on aircraft with 18 passenger seats and low sonic boom. The Spike S-512, capable of Mach 1.6, is a windowless twin-engine design with panoramic interior displays of the view outside. The Aerion AS2, in contrast, still has windows, but three engines; it will be capable of Mach 1.4. The private jet service Flexjet placed an order for 20 Aerions in 2015. The two companies want to have aircraft flying in 2023.

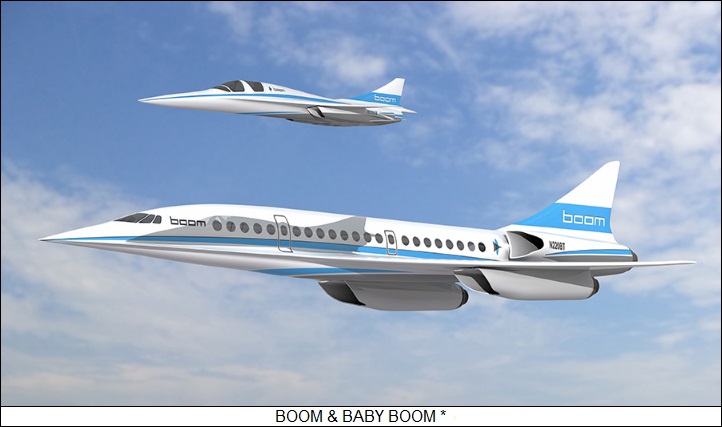

The Boom company isn't interested in reducing sonic boom, preferring instead to develop a 45-seat airliner for trans-oceanic flights at Mach 2.2 (2,335 KPH / 1,450 at cruise altitude). Boom's machine will be 52 meters (170 feet) long, and cruise at supersonic speed without afterburner. According to CEO Blake Stoll: "Carbon fiber composites, aerodynamic, and propulsion strategies that are efficient enough [will] help us reach that level of operating cost."

Boom is working on a 1/3-scale, two-seat "Baby Boom" prototype to fly in 2018, a full-size prototype by 2020, with service flights in 2023. Richard Branson of the Virgin Group has ordered the first 10 airplanes, and offered to provide engineering support from Virgin Galactic; Japan Air Lines has also placed orders. There hasn't been much progress on SSTs for decades, but now things seem to be rolling.

* As further evidence of this, an article from AVIATIONWEEK.com ("Supersonic X-plane Takes Next Step To Reality" by Guy Norris, 7 June 2017) says that the US National Aeronautics & Space Administration (NASA) has now issued a draft request for proposals for development of a "Quiet Supersonic Transport (QueSST)" low-sonic boom flight demonstrator, with the first flight of the new X-plane in early 2021.

Lockheed Martin has come up with a preliminary design of a low-boom demonstrator concept under a 17-month, $20 million USD contract. Companies submitting proposals for QueSST are free to come up with their own designs, as long as they meet spec. Rob Weiss -- Lockheed Martin's Advanced Development Programs executive vice president and general manager -- feels his company has obtained a leg up on QueSST from the study: "We are ready to go on building that demonstrator ... we feel we have a technological advantage in the amount of investment we have made in the tools and the vehicle itself."

NASA will award the contract in the first quarter of 2018. This will be the first time the agency has worked on a purpose-built, piloted supersonic X-plane since the experimental thrust-vectoring X-31 in 1990. Flight testing in 2021 will focus on aircraft validation, while testing in 2022 will investigate boom characteristics.

COMMENT ON ARTICLE* IMPROVING AFRICA'S CROPS: As discussed by an article from ECONOMIST.com ("No Crop Left Behind", 23 November 2017), Africans raise a number of crops unfamiliar or under-appreciated in developed countries: cassava and sweet potatoes; lablab beans and water berries; bitter gourds and sickle sennas; Elephant ears and African locusts. Sweet potatoes are known everywhere, but elephant ears? They're a leafy vegetable. African locusts? Legumes that grow on trees. However familiar or unfamiliar these crops are, they have one thing in common: they're not big cash crops in developed countries, and so there hasn't been much interest in improving them.

Cereal crops like rice, wheat, and maize have had their genomes mapped out, and have been the focus of intensive crop improvement, making them far superior to their ancestors of only two centuries ago. The "orphan crops" on which Africans are heavily dependent have seen little such improvement. They aren't as nutritious as they need to be, the result being widespread malnourishment. A report from the World Health Organization estimates that almost a third of Africa's children, nearly 60 million of them, are stunted. Researchers at the World Bank reckon the effects of stunting have reduced Africa's GDP by a tenth.

Two recent, interrelated projects are working to improve orphan crops. They are both based in Nairobi, being conducted under the umbrella of the World Agroforestry Center -- an international non-governmental research organization. The first project is the "African Orphan Crops Consortium (AOCC)"; the other is the "African Plant Breeding Academy". The AOCC's mission is to obtain complete sequences of the DNA of 101 neglected food crops, while the academy's is to disseminate those sequences, and much other data, to young scientists from universities and other institutes around the continent.

The AOCC is largely the brainchild of Howard-Yana Shapiro. His official job is as chief agricultural officer of Mars, a well-known US candy-maker. As discussed here in 2012, Mars researchers once sequenced the genome of cacao, the source of chocolate, in order to improve one of the firm's most important raw materials. When Shapiro ran into Ibrahim Mayaki, the head of an African development agency known as "NEPAD", Mayaki suggested that other tropical crops should be sequenced. Shapiro liked the idea, with the duo then recruiting Tony Simons -- who runs the World Agroforestry Center -- and Rita Mumm -- a plant geneticist at the University of Illinois. In 2013, the group launched the consortium and the academy.

To date, AOCC has fully sequenced the genomes of ten orphan crop plants, and partially sequenced 27 others. Once complete genomes are available, the differences between those of different natural varieties of the same species, known as "landraces", can be identified. Very importantly, full sequencing allows maps of DNA markers within a genome to be constructed, with the markers then used to nail down the movement of blocks of DNA from parent to offspring when different landraces are crossed.

Traditionally, crop hybridization was a basically hit-or-miss affair: varieties with desired traits were crossed, with the offspring inspected to see if exhibited the traits as hoped. With the traits linked to genetic markers, the offspring can be inspected for the desired markers, with those that don't being discarded. The end result is accelerated development of new hybrid crop varieties that have better yields -- because of virus, pest, or drought resistance, for example -- or better nutritional value -- such as enhanced vitamin content -- or both.

In the meantime, the academy has brought in 81 researchers from all over Africa for what amount to "master classes" from the world's top plant breeders. As part of their studies, the researchers are informed of the consortium's latest results, so they can then apply those results to their work.

As an example, Dr. Robert Mwanga -- a Ugandan at the International Potato Center, who has long advocated improvement of African crops -- has worked on improving the sweet potato. The varieties of sweet potato available in Uganda and elsewhere in Africa in the 1980s were deficient in vitamin A, resulting in damage to the eyes and brain of children, as well as making them more vulnerable to disease.

Starting with Asian varieties that had more vitamin A in them, Mwanga bred a dozen strains richer in vitamin-A and with more dry matter -- meaning more calorific value -- than African landraces. He then led a campaign to encourage local farmers to adopt the new varieties, the farmers proving enthusiastic. Mwanga won the World Food Prize in 2016 for his work. Mwanga is now working on virus resistance, viral infection being a big problem for sweet potatoes. Other African crop researchers, graduates of the Nairobi academy, are following Mwanga's example:

As Mwanga understood, it wasn't enough to come up with new crop varieties: farmers had to be persuaded to plant them. Farmers, particularly those at a subsistence or near-subsistence level, are resistant to change. When they did initially adopt Mwanga's improved sweet potatoes, they only used them for animal fodder, since the new potatoes were orange while the old ones were white. Mwanga patiently encouraged them to grow such crops for human consumption. He also found it useful to work with seed companies, having worked with two Ugandan firms -- BioCrops and Senai -- to distribute the latest varieties of the new sweet potato.

At present, most of the work on crop improvement is focused on subsistence farming -- but, as Oselebe's work suggests, there is a potential for bigger markets. The developed world has long demonstrated an inclination to adopt new and exciting fruits and vegetables: bananas, mangoes, pineapples, and pawpaws are all tropical fruit that have gone global. Improving Africa's orphan crops may not just help Africans stay healthy; it also promises to make them more prosperous.

COMMENT ON ARTICLE* UNDERSTANDING AI (8): As discussed by article from TIME.com ("Google Wants to Give Your Computer a Personality" by Lisa Eadicicco, 16 October 2017), for a long time machines that could hold conversations with humans were lab toys, useless in the real world. Over the past few years, however, voice-enabled gadgets have become a red-hot technology. Android Assistant (A2) is available on phones from the likes of Samsung and LG, while Amazon.com offers its take, Alexa, on the firm's popular Echo speakers. Apple has built Siri into many of its iDevices, and Microsoft is putting its Cortana helper in everything from tablets to thermostats. Now, tens of millions of Americans use Assistant, Alexa, or another virtual butler at least once a month, with sales of smart speakers alone soaring up into sales worth billions a year.

Right now, these voice-enabled digital assistants are limited in their conversational capabilities: they're given orders, and carry them out. Google, which has built a monster business by providing "information on demand", sees truly conversational machines as a next big step in its services. To create machines with personalities, the company has assembled a team of creative types not traditionally seen as Googlers: fiction writers, film-makers, video-game designers, psychologists, and comedians.

Computer scientists had worked on giving machines conversational capabilities from the beginning. The first "virtual assistant" recognizable as such was Microsoft's "Clippy", an animated paper clip that was supposed to be helpful, introduced as an element of MS Windows in 1997. Clippy's primary usefulness turned out to be as a bad example, since people generally found him irritating, and rarely of much help. He was quietly deleted from Windows in 2007.

The concept behind Clippy -- predicting what information a user might need next, providing tips when they seemed necessary -- actually wasn't a bad one. In 2011, Apple introduced Siri, which did the job much better. Siri also integrated voice to a degree, which was particularly handy in a smartphone, where keyboard input tends toward the troublesome. Soon, everyone was jumping on the virtual assistant bandwagon, with Google developing Assistant.

37-year-old Ryan Germick heads the Google team working on the A2's personality. He sees the mission in straightforward terms: "We want you to be able to connect with this character. Part of that is acknowledging the human experience and human needs. Not just information, but also how we relate to people."

This is a subtle and tricky task. One of the problems, in giving A2 a personality, is avoiding the inclination to make it pretend to be a human. In 1970, the Japanese roboticist Mori Masahiro coined the term "uncanny valley", suggesting that the more a machine tried to fake being a human, the more people regarded it as a fake. People regard a robot like R2D2 as cute; they tend to find the robot Lincoln at Disneyland a curiosity at best, weird at worst. It is, by that coin, not surprising that Google called their virtual assistant simply "Assistant" -- implying an obedient servant -- and did not give it a human name like "Siri" or "Alexis".

In other words, a virtual assistant has to be seen as a synthetic character, a sort of cartoon character like Mickey Mouse or Bugs Bunny, that people like, but don't confuse with a real human being. Emma Coats, the "character lead" of the A2 personality team, has plenty of experience in constructing cartoon characters. She worked for five years at Pixar Animation Studios on animated movies like MONSTERS UNIVERSITY, BRAVE, and INSIDE OUT.

With a conversational system like A2, the machine personality is all about responses -- after all, A2 never does anything on its own initiative. Coats points out the kinds of questions team members ask when crafting an appropriate response:

For example, she says, consider a user asking Assistant if it's afraid of the dark. It would be fake to say it was, a conversational dead end to just reply NO, so what A2 says is: "I like the dark because that's when stars come out. Without the stars, we wouldn't be able to learn about planets and constellations."

Think of it as a taste of entertaining light philosophy. It's maybe not that much more than what one might get out of a fortune cookie -- but people like fortune cookies. Coats says: "This is a service from Google. We want to be as conversational as possible without pretending to be anything we're not." [TO BE CONTINUED]

START | PREV | NEXT | COMMENT ON ARTICLE* ONCE & FUTURE EARTH (22): There is no doubt that greenhouse warming of the planet does take place, since otherwise the Earth would be an icebox. There are four principal greenhouse gases:

Anyone reading this list might have reason to feel puzzled, because it clearly shows that water vapor is the most important greenhouse gas. So why the fuss over CO2? However, the effect of CO2 is not negligible, that effect ranging in possible value from about a tenth to a quarter of the whole -- and there are good reasons to believe CO2 is the "lever" in the system.

One of the characteristics of CO2 is that the "sinks" that draw it out of the atmosphere, most significantly through the photosynthetic operation of plants, operate slowly. That means that a rise in CO2 concentrations can take a long time to fall back down. Water, in contrast, simply falls out of the sky as precipitation, and water vapor concentrations can change very rapidly -- everybody knows that the weather can shift from humid to dry overnight. CO2 concentrations don't, can't fluctuate anywhere near that rapidly.

Obviously, water vapor is produced by evaporation, mostly from the seas, and also obviously, an increase in global temperatures means a higher rate of evaporation. That suggests a temperature increase due to a rise in CO2 concentrations could well be amplified by positive feedback from an increase in water vapor concentrations. As noted, the concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere are small, a fraction of a percent. That means its effectiveness as a greenhouse gas is disproportionately greater than of water vapor on the basis of the total mass of each gas, and so increments in the concentrations of CO2 could have a disproportionate effect.

All that said, water vapor occupies an ambiguous position in the global warming debate. Although it is certainly a greenhouse gas and helps trap heat, as water vapor concentrations rise it also produces more cloud cover -- and, in winter, more snowfields -- reflecting more sunlight back into space. To confuse matters further, clouds also reflect radiation from below, helping trap more heat; in addition, condensation of water droplets is an exothermic process, it releases energy, and so formation of clouds tends to produce local warming. After considerable discussion, the general consensus in the climate research community is that more water vapor means, overall, more warming.

* So what does real-world data show? Measurements made from the 1950s show the level of CO2 rose from 316 parts per million (PPM) in 1959 to 387 PPM in 2009. Indirect measurements suggest the rise began about 1750, starting from the 280 PPM that appears to have been the long-term average for the 10,000 years before that -- though everyone acknowledges that natural CO2 concentrations did tend to vary around that average.

The timing of the rise in CO2 concentration from 1750 tracks the rise in human population and industrialization. It is true that the relative proportion of human emissions of CO2 to natural emissions is small -- but while natural processes have been producing CO2 for a lot longer than humans have been around, they also provide sinks that soak up the CO2, keeping the levels roughly constant. Human activity has provided a persistent increment of CO2 emissions that natural processes can't quite keep up with, a trickle that is gradually leading to an overflow. Estimates suggest that humans produce CO2 in the range of 25 to 30 gigatonnes a year; the rate of growth needed to account for the parts-per-million changes observed is about 15 gigatonnes per year, which is roughly only half the human contribution.

But what is the actual effect of that overflow? It's not entirely clear from the data just how temperature rises with CO2 concentration, or in other words what the "sensitivity" of climate to CO2 concentration really is. Climate is a noisy phenomenon, making it hard to spot and track changes, and the oceans can absorb a good deal of heat, inserting considerable inertia into the system.

Climate records now available do support warming. There were protests that analyses that showed warming were biased, or suffered from confounding effects in measurements -- but all professional organizations that have analyzed the data, including national weather agencies, have come up with the same results, with all known confounding effects factored into the analyses. [TO BE CONTINUED]

START | PREV | NEXT | COMMENT ON ARTICLE* Space launches for December included:

-- 02 DEC 17 / LOTOS (COSMOS 2524) -- A Soyuz 2-1b booster was launched from Plesetsk at 1043 UTC (local time - 3) to put the "Cosmos 2524) satellite into orbit. It was believed to be the third "Lotos" electronic intelligence satellite -- missions, following the launch of a Lotos test satellite in November 2009 and a follow-up launch of the first Lotos payload in December 2014.

-- 03 DEC 17 / LKW 1 -- A Chinese Long March 2D booster was launched from Jiuquan at 0411 UTC (local time - 8) to put the "LKW 1" satellite into Sun-synchronous orbit. It was believed to be an optical surveillance satellite.

-- 10 DEC 17 / ALCOMSAT 1 -- A Chinese Long March 3B booster was launched from Xichang at 1640 UTC (next day local time - 8) to put the "Alcomsat 1" geostationary comsat into orbit for the government of Algeria. The satellite was based on the DFH-4 satellite design manufactured by the China Academy of Space Technology, with a launch mass of 5,225 kilograms (11,520 pounds) a 15-year service life, and a payload of 19 Ku-band / 12 Ka-band / 2 L-band transponders. It was placed in the geostationary slot at 24.8 degrees west longitude.

-- 12 DEC 17 / GALILEO 19:22 -- An Ariane 5 ES booster was launched from Kourou at 1836 UTC (local time + 3) to put four "Galileo" navigation satellites into orbit, bringing the total number of satellites in space up to 22. These were the 19th through 22nd Galileo satellites launched, being the 15th through 18th of the fully operational constellation (FOC) satellites.

The four satellites in this launch weighed roughly 715 kilograms (1,575 pounds); they featured two passive hydrogen maser atomic clocks; two rubidium atomic clocks; clock monitoring and control unit; navigation signal generator unit; L-band antenna for navigation signal transmission, C-band antenna for uplink signal detection, two S-band antennas for telemetry and tele-commands, plus a search and rescue antenna. They were built by OHB Systems in Germany, with Surrey Satellite Technology of the UK supplying the navigation payloads. The complete Galileo constellation will consist of 30 satellites along three orbital planes in medium Earth orbit, including two spares per orbit.

-- 15 DEC 17 / SPACEX DRAGON CRS 13 -- A SpaceX Falcon booster was launched from Cape Canaveral at 1536 UTC (local time + 5), carrying the 13th operational "Dragon" cargo capsule to the International Space Station (ISS). It docked with the ISS Harmony module two days after launch. The Falcon first stage performed a soft landing at Cape Canaveral; it had been launched and recovered on a previous mission. The Dragon capsule was also recycled from a previous mission.

-- 17 DEC 17 / SOYUZ ISS 53S (ISS) -- A Soyuz booster was launched from Baikonur at 0721 UTC (local time - 6) to put the "Soyuz ISS 53S" AKA "Soyuz MS-07" manned space capsule into orbit on an International Space Station (ISS) support mission. The crew included vehicle commander Anton Shkaplerov of the RKA (third space flight), flight engineer Scott Tingle of NASA (first space flight), and astronaut Kanai Norishige of JAXA (first space flight). The Soyuz capsule docked with the ISS Rassvet module two days after launch, the three spacefarers joining the ISS Expedition 54 commander Alexander Misurkin, and NASA astronauts Mark Vande Hei and Joe Acaba.

-- 23 DEC 17 / CGOM-C, SLATS -- A JAXA H2A booster was launched from Tanegashima at 0126 UTC (local time - 9) to put the "Global Changing Observation Mission-Climate (GCOM-C)" space platform the "Super Low Altitude Test Satellite (SLATS)" into orbit for the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA).

GCOM-C AKA "Shikisai (Color)" had a launch mass of 2 tonnes (2.2 tons) and carried a wide-area global imaging instrument payload -- including a visible radiometer, a near-infrared radiometer, and an infrared scanner. During its five-year mission, it was to perform surface and atmospheric measurements related to the carbon cycle and radiation budget, such as clouds, aerosols, ocean color, vegetation, and snow and ice.

SLATS AKA "Tsubame (Swallow)" was an experimental technology demonstration satellite carrying an ion engine; it flew in a "super low" orbit where it encountered greater air resistance than most spacecraft, with the ion engine maintaining it in orbit. It had a launch mass of 400 kilograms (880 pounds); it was aerodynamically designed, and featured a coating on its thermal insulation to protect it from abrasion. It carried an imager to take pictures of the Earth.

-- 23 DEC 17 / IRIDIUM NEXT 31:40 -- A SpaceX Falcon 9 booster was launched from Vandenberg AFB at 0127 UTC (previous day local time + 8) to put ten "Iridium Next" satellites into orbit. The launch left an awe-inspiring trail in the evening sky that attracted considerable public attention. The Falcon booster first stage had been flown before, but was not recovered.

-- 23 DEC 17 / LKW 2 -- A Chinese Long March 2D booster was launched from Jiuquan at 0414 UTC (local time - 8) to put an Earth observation payload designated "LKW 2" into orbit. It was announced as an Earth survey satellite, but was judged to be a military optical surveillance satellite.

-- 25 DEC 17 / YAOGAN 30 x 3 -- A Long March 2C booster was launched from Xichang at 1944 UTC (next day local time - 8) to put the secret "Yaogan 30" payloads into orbit. It was a triplet of satellites -- including Yaogan 30G, 30H, and 30I -- and may have been a naval signals intelligence payload.

-- 26 DECR 17] / ANGOSAT -- A Ukrainian Zenit booster was launched from Baikonur at 1900 UTC (next day local time - 6) to put the "AngoSat" geostationary communications satellite. Built by RSC Energia in Russia, AngoSat had a launch mass of 1,647 kilograms (3,631 pounds). It was Angola's first satellite; communications were lost on arrival into orbit, but ground controllers managed to regain contact.

COMMENT ON ARTICLE* RABIES VERSUS BRAIN CANCER: Sometimes medical researchers almost seem to go out of their way to shock the public. As a case in point, consider the title of an article by Matt Blois, dated 10 February 2017, from SCIENCEMAG.org: "How To Stop Brain Cancer -- With Rabies".

Rabies is a particularly fearsome disease because it attacks the brain. It is adapted to do so, using its ability to infect nerve cells as a conduit through the "blood-brain" barrier that prevents other pathogens from reaching the brain via the bloodstream. That same blood-brain barrier also complicates treatment of brain cancer. South Korean researchers, inspired by a dark Zen, have seen an opportunity in the ability of the rabies virus to infiltrate the brain -- leveraging off the virus to ferry tumor-killing nanoparticles into brain tumors, targeting them for elimination.

Researchers have already packaged cancer-fighting drugs into nanoparticles coated with part of a rabies surface protein that lets the virus gain access into the central nervous system. Nanoparticle expert Youn Yu Seok and his team at Sungkyunkwan University in Suwon, South Korea, have taken that approach a step further, having engineered gold particles so that they have the same rodlike shape and size as the virus. Once coated with the surface protein, that shape improves the ability of the nanoparticle assembly to bind with receptors on nerve cells, to then use the nerve cells to gain access into the brain. The nanoparticles don't carry drugs, the gold element being the therapeutic element; it absorbs infrared laser light that can penetrate into the brain, to heat up and destroy surrounding tissue.

To test the efficacy of their nanoparticles against tumors, Youn and his team first injected them into the tail veins of four mice with brain tumors. The nanoparticles quickly made their way to the brain, where they accumulated near the tumor sites. The researchers then illuminated the nanoparticles with a near-infrared laser, heating them to about 50 degrees Celsius (120 degrees Fahrenheit). The tumors shrank dramatically. In another experiment, the researchers used the same treatment on mice with tumor cells that had been injected into their flanks. Tumors on two of the mice disappeared after 7 days, whereas the other tumors shrank to about half their original size.

Youn is not certain as to how the nanoparticles targeted the tumor cells. That they did is not disputed, but there's no saying at this time that they're all that selective, and so the treatment might be damaging healthy tissues as well. Chen Feng, a materials scientist at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, also worries about toxicity. Large nanoparticles along the lines of those used in Youn's experiment often end up in the liver and take a long time to clear out. However, Youn sees the approach as very promising, and believes that proper design of the nanoparticles will minimize side effects: "Researchers need to develop [nanoparticles] precisely and effectively to target tumors. That's my obligation."

COMMENT ON ARTICLE* HUMAN PHAGEOME: The bacteriophages -- viruses that infect bacteria -- were discovered late during World War I. As discussed by an article from SCIENCEMAG.org ("Does A Sea Of Viruses Inside Our Body Help Keep Us Healthy?" by Giorgia Guglielmi, 21 November 2017), researchers are now zeroing in on the role that "phages" play in keeping us alive and healthy.

There was interest after the First World War in using phages to treat bacterial infections. There was considerable activity in the Soviet Union, but the approach never caught on elsewhere. One of the reasons for the disinterest was a failure to truly appreciate the universality of phages; they're found everywhere, from oceans to soils. Now a study suggests that humans absorb up to 30 billion phages a day through their intestines. The significance of that fact is, at present, unclear, but it reinforces growing interest among scientists who wonder what influence the vast numbers of phages in the human body, the "phageome", has on our physiology. Do phages regulate our immune system?

Phage researcher Jeremy Barr -- of Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, previously at the University of San Diego -- says that traditionally, phages were seen as having little or no role in the body, being merely there to infect the bacteria we host: "Basic biology teaching says that phages don't interact with eukaryotic cells." Now he's concluded "that's complete BS."

Early on in his research, as mentioned here in 2013, Barr felt that the focus on phages as antibiotics was too narrow; he wanted to take a wider look and see what turned up. His initial studies of phages showed that they might be acting as complements to the human immune system, protecting us from bacterial pathogens. Investigating animals ranging from corals to humans, Barr and his team found that phages are four times as abundant in mucus layers, like those that protect our gums and gut, as they are in the adjacent environment. It turned out that the protein shell of a phage can bind "micins" -- large secreted molecules that, together with water, make up mucus. The result was a minefield for bacteria, keep bacterial pathogens from reaching the cells underneath.

Now Barr has found that phages in the gut's mucus can make their way into the body. In lab dish experiments, his team showed that human epithelial cells -- such as those that line our guts, lungs, and the capillaries surrounding the brain -- take up phages and transport them across their interior. The researchers haven't figured out how they do it yet, but it's certain they do it, since the phages could be found enclosed in vesicles within the cells. The transfer was effectively one-way as well, from an exterior surface -- like the gut lining -- to the interior. The researchers estimated the rate of transfer of phages in a typical human as about 30 billion a day.

Molecular biologist Krystyna Dabrowska -- of the Polish Academy of Sciences's Institute of Immunology and Experimental Therapy in Wroclaw -- warns that what happens in a lab dish is not necessarily what happens in the human body. She is nonetheless intrigued by Barr's research, since it poses a question of interest to her own research: what are the phages doing after they have been absorbed into the body?

In 2004, researchers led by Dabrowska reported that a specific type of phage can bind the membrane of cancer cells, damping tumor growth and spread in mice. A few years later, her graduate adviser, phage expert Andrzej Gorski, showed that phages can affect the mouse immune system when injected, ramping down T-cell proliferation and antibody production. In mice, they can even prevent the immune system from attacking transplanted tissues.

Barr himself suspects that in humans, a steady influx of the viruses creates an "intrabody phageome", which may modulate immune responses. Recent studies reinforce that idea:

Barr suspects the phageome might be an immune-system signal. For example, a particular bacterial infection would produce phages targeting that bacteria in response. Once these phages are presented to the human immune system, it would target the bacteria as well.

Barr cautions that he's only speculating, thinking of attractive paths for future research. He says we don't know enough yet, that "phage biology is an inch wide and a mile deep." Medical applications? He says they "are probably decades away."

COMMENT ON ARTICLE* UNDERSTANDING AI (7): As discussed by an article from ECONOMIST.com ("The Latest AI Can Work Things Out Without Being Taught", 21 October 2017) one of the checkpoints in the history of artificial intelligence technology was in 1997, when IBM's Deep Blue computer defeated chess master Garry Kasparov. Chess, it turns out, is not the toughest traditional game to master: it wasn't until 2016 that a computer defeated master players of the Asian game of Go, with a program named "AlphaGo", developed by DeepMind, defeating Go master Lee Sedol.

Go is a deceptively simple game, with players occupying intersections on a board grid of 19 x 19 lines with white versus black stones as per simple rules; whoever has the most stones when the game runs out of possibilities wins. However, the game requires an ability to think in depth and detail, leading to a "combinatorial explosion" that defeated a brute-force approach, and so long stymied computers.

AlphaGo used AI instead of the brute-force approach. The program learned to play Go by supervised learning, studying thousands of games between expert human opponents, extracting rules and strategies from those games, and then experimentally playing millions of matches against itself.

Although AlphaGo ended up able to defeat any human player, DeepMind researchers still felt it could be further refined. They moved on to an improved version, "AlphaGo Zero", which was more competent at the game, acquired expertise much more quickly, and didn't require as much computing horsepower. Most significantly, however, AlphaGo Zero learned how to become an expert Go player without reference to human players.

As with chess players, Go players focus on strategic visions and tactical "tropes" to play the game. Players talk of features such as "eyes" and "ladders", and of concepts such as "threat" and "life-and-death". The original AlphaGo, through supervised learning, acquired the visions and ploys of human players.

The problem with supervised learning is that giving an AI system an adequate set of examples to learn from is very laborious and expensive. It also limits the AI system to human ways of doing things. A computer doesn't have the built-in biases of the human brain; it may be able to come up with its own ways of thinking out tasks that work better.

AlphaGo Zero discarded supervised learning. The program started with only the rules of the game and a "reward function" -- which awarded a point for a win, and docked a point for a loss, the software's goal being to maximize wins. AlphaGo Zero originally just placed stones at random; but after one day it was playing at an advanced professional level, and after the second day, it could defeat the original AlphaGo.

In simpler terms, AlphaGo Zero rediscovered for itself effectively everything humans had ever learned about playing Go. Its creators, observing its progress, sometimes found it strangely humanlike, making errors exactly like those of human novices, which it quickly outgrew. At other times, it went off in strategic directions that made no sense to a human player, discarding those that didn't work, retaining those that did. Expert Go players in combat against AlphaGo Zero found it alien, superhuman, as far beyond those expert human players as they were beyond skilled amateurs.

That gives fuel to those who fear AI, that it will eventually outpace humans in all respects. However, expert Go players don't seem unduly worried about AlphaGo Zero showing them up -- any more than weightlifters are concerned by the fact that a fork lift can pick up and carry around far more weight than any human can. That's precisely why there are fork lifts. In fact, expert Go players have found being beaten by AlphaGo Zero educational, since some of its strategies and tactics are completely unfamiliar, providing instruction to humans on how to play a tougher game.

Besides, as before, Go is a structurally simple game with a handful of clearly-defined rules, and relatively easy for a machine to get a grip on; not all difficult tasks that humans can accomplish are so well-structured. When taking on a poorly-defined task such as planning a vacation, humans draw on powers of reasoning and abstraction that so far elude AI software.

They may always do so; why would we want a machine to, say, tell us what kind of a vacation we want to take? At most, we could tell it where we want to go and what we want to do, then let it offer options and work out the specifics. We would nonetheless have to realize there is no game of pure strategy that a machine won't be able to beat us at, sooner or later.