* Entries include: shipping infrastructure, Pacific coast road trip, augmented reality systems, Arab unhappiness, consciousness examined (sort of), toilets for the developing world, a short history of the census, ethanol versus water supplies, electric drive for ships and planes, online games to do work, using terrorists to fight terrorism, & solar America plan.

* NEWS COMMENTARY FOR MARCH 2008: At the beginning of March, the Colombian military staged a raid against a FARC guerrilla camp across the border in Ecuador, killing the executive officer of the group, Paul Reyes. The Ecuadorian government was furious at the incursion and sent troops to the border region; Venezuela's Hugo Chavez mobilized forces in sympathy.

Colombian officials apologized for the raid, but insisted that it was justified. They also trumpeted documents obtained from a laptop PC snatched in the raid in which FARC officers discussed obtaining $300 million USD from Venezuela, with the documents talking about how Chavez wanted to undermine the US-allied Colombian government. Venezuelan spokesmen denounced the documents as fabrications. After about a week of squabbling, the sides came to an agreement and all was at least superficially agreeable again.

* The US invasion of Iraq passed its fifth unhappy anniversary in March, with BBC.com running a series of reports on where Iraq is now. Iraqis are actually feeling much more secure than they did, being able to go outdoors casually and enjoy themselves -- as long as they stick to their own neighborhoods. Moving around in other places is still very dangerous. They have a fairly high degree of confidence in the reconstituted Iraqi military, not much confidence in the Iraqi government, and find the lack of services -- clean water, power, and so on -- particularly troublesome.

A commentator on BBC observed that the improvement in security is generally attributed to improved US military tactics, with the media praising the leadership of Army General David Petraeus, the theatre commander -- a man whose seems to radiate competence in interviews. The relative peace is also due to the inclination of Iraqi militias to stand down, at least for the moment. That tends to imply that everything might well go to hell again if the Americans left abruptly. However, it appears that the US military in Iraq feel they have a handle on the situation for the time being, and can contemplate, even hope for, five or possibly ten more years in Iraq, at least as long as fighting is well more the exception than the rule, and they can get the number of troops down from 150,000 now to 80,000 or so.

The commentator pointed out that one of the things the Americans did to improve security was set up Sunni insurgent militias as paramilitary units to protect their own neighborhoods and towns. The problem is that if general Sunni-Shiite fighting breaks out again, the Sunnis have the capability to effectively resist government forces, and if the Americans left abruptly the fighting would probably reach new levels of violence. The Americans realize that only a workable political settlement is going to resolve the situation over the long run. It is interesting to speculate if creating a more even balance of power between Sunnis and Shiites might actually help promote a solution.

* In less contentious news, French President Nicholas Sarkozy paid a state visit to the UK, with considerable media interest in his new bride, model and singer Carla Bruni. The British tabloids were not shy about printing discreetly censored pictures of Madame Sarkozy in the buff from her modeling days. The visit was brief and short on substance, but Sarkozy went to great lengths to praise the British and suggest closer coordination between the two nations, whose histories have been long entangled by common interests -- as well as, though Sarkozy was tactful not to say, by rivalries and culture clashes.

The visit went over well. British Prime Minister Gordon Brown talked of the two nations in an "Entente Formidable" -- while many Americans might not think of the UK and France as major military powers, they are the only two European nations in NATO with a serious capability for "force projection" overseas. Despite the lewd pictures in the tabloids, which could have been expected, overall UK media coverage was gushing, with French papers running more or less appreciative titles such as: "When The British Press Suddenly Starts Liking The French".

Sarkozy's marriage to Bruni had not gone over well at home, since it suggested that the president, previously regarded as determined and focused even by his enemies, was frivolous and infatuated with celebrity glitz. However, Madame Sarkozy's performance in the exercise got good grades in the French media, some saying she compared more than favorably with Sarkozy's first wife, Cecilia. It was certainly amusing to see videos of her being chatted up by Prince Philip.

* As if the current US presidential election campaign wasn't lively enough, the American public also got a political sex scandal as a sideshow. New York Governor Eliot Spitzer, who had risen to power through a reputation as a tough prosecutor who had hammered the Mob as well as Wall Street corruption, got stung bringing a high-class prostitute to a Washington DC hotel. Spitzer was discreetly known as "Client 9" on the books of the escort service, but he was caught dead to rights, being forced to make a humiliating public admission of guilt and plea for forgiveness, with his wife at his side. Given his reputation for incorruptibility, his fall from grace was particularly devastating. THE ECONOMIST ran an essay on his downfall, headed by a cartoon of Spitzer dressed as a crusader knight, lopping off his own head with his own sword in good Monty Python fashion.

Spitzer resigned a few days after the story broke. The general belief was that even though he was a prominent Democrat, the scandal was not going to have much influence on election politics. The Republicans might have felt some satisfaction, but they were reluctant to gloat too much publicly because prominent Republicans had been nailed in sex scandals as bad or worse over the past few years, and there was no saying there wasn't another fiasco lurking in the wings. It is said, however, that Wall Street found the circus entirely entertaining, with Photoshopped pictures of Spitzer at play with various hot babes pinned up on the trading floors.

* In the "world as a Disney movie" category of the news for March, according to the BBC, two pygmy sperm whales got disoriented in a bay on the North Island of New Zealand and repeatedly beached themselves, despite the efforts of a conservation officer and a few citizens to get them back out to sea. Then a dolphin well known to locals for playing with swimmers and named "Moko" showed up and guided the two whales out of their predicament.

Humans have a tendency to read into animal behavior things that aren't necessarily there. There are old stories of fur trappers and the like being "warned" by the cawing of crows that there was a cougar lurking nearby, though in modern times the general belief is that the crows were tipping the cougar off to the location of a potential meal in hopes of getting table scraps. However, in this case it was hard to believe something wasn't going on. Said the conservation officer: "I don't speak whale and I don't speak dolphin, but there was obviously something that went on because the two whales changed their attitude from being quite distressed to following the dolphin quite willingly and directly along the beach and straight out to sea." One wonders if the dolphin was saying something along the lines of: "Oh, what sort of mess have you two got yourself into? Come along, the ocean's this way. Whales -- they're such nitwits."

BACK_TO_TOP* INFRASTRUCTURE -- SHIPPING (4): Container shipping has substantially altered the appearance of the waterfront. In the old days, a port was crowded with longshoremen and other workers, with sacks and crates and barrels of cargo piled on the wharfs and in warehouses. There were offices for shipping agents, union halls, and a tavern or two to service the workers.

These days, a "container terminal" is more like a parking lot, littered with containers and lined along the waterfront with huge cranes to handle the containers. The cranes are more robust than construction cranes but they are also less flexible, since all they have to do is pick up containers, move them from ship to shore or the reverse, and put them down again. Interestingly, the cranes are often brightly painted -- they're visible from a long distance, and there's no reason to make them more of an eyesore than they need to be.

When not in use, the crane boom is pulled up, to keep it out of the way of ship traffic. In operation, the boom extends over the ship being loaded. The size of the crane is linked to the size of the container ships; the biggest cranes have an "outreach" of about 43 meters (140 feet), meaning they can reach that far over the top of the vessel being loaded, and lift a container up to a height of 30 meters (100 feet). The operator sits in a climate-conditioned cab that moves along the bottom of the boom. Operating a dockyard crane is not a trivial skill: the containers have to be set down very precisely, and it has to be done rapidly.

In operation, a tractor-trailer rig with a container drives up to the crane, which then drops a "spreader" that mates to the container. The crane picks up the container and transfers it to the container ship, dropping it neatly into place, where shipboard workers lock it down using its corner fittings. For unloading, the process is reversed. Thanks to the container system, a freighter that would have taken hundreds of workers a week to load or unload a century ago can be handled by a dozen workers in an afternoon.

* Not surprisingly, containers can't be loaded onto a container vessel in any old order; if a ship is heading for multiple ports, it would be counterproductive to put the containers for the first ports of call underneath those intended for later ports of call. There are other constraints -- for example, the load on the ship has to be balanced so it isn't inclined to capsize, and containers with refrigeration systems have to be placed in certain locations on the ship where they have access to electrical power. Figuring out the proper loading order of containers is tricky, and these days it's done with planning software.

Incidentally, the tractor-trailer rigs that transfer containers to or from the cranes are local to the container terminal. They're known as "hustlers" and they shuttle back and forth to staging areas in the shipyard; their name comes from the fact that they're in constant rapid motion and can be a hazard to the unwary walking around a terminal. The hustlers are loaded or unloaded in the staging area by either specialized forklifts or a four-wheeled tall rolling "frame" called a "straddle carrier". Of course the staging area is where the containers are sent out from (or brought in to) the container terminal by land transport, meaning long-haul tractor-trailer rigs or trains. [TO BE CONTINUED]

START | PREV | NEXT* GIMMICKS & GADGETS: THE ECONOMIST ran an article on the latest in cellphone technology: the "femtocell". The femtocell isn't a variation on the cellphone itself, it's a scaling down of the cellphone network. The idea is to obtain a wireless "base station" that operates over the range of about a household, with the base station linked to a fast internet connection. Regular digital cellphones can be used on the femtocell, with the conversations being conducted through "voice over internet protocol (VOIP)".

The idea of femtocells is to get around wireless charges -- people do a lot of calling at home, and they could do their "heavyweight" downloads of video and music before going out the door. Wireless operators are not displeased with the idea, since once femtocell users leave the home, they still have to use the wider wireless network; the operators still get their basic contracts, and they don't have to install more wireless infrastructure to keep up with demand. Makers of wireless infrastructure less happy.

There are difficulties with the concept, however. Femtocells are basically "do it yourself" networks, which means they have to be easy to set up, and there's always the classic wireless bogeyman of interference. Worst of all, the femtocell base stations are expensive for the time being and operators offering them are asking relatively steep subscription prices, negating the value of the scheme. Advocates believe that rationality will prevail in the near future, and that femtocells could be as "disruptive" in the wireless domain as personal computers were in the computing domain. Industry observers are taking a wait-and-see attitude.

* IEEE SPECTRUM had an interesting short article on an ultralow power "system on chip (SOC)" intended to be used as the nodes of a wireless "body area network" that can be applied in a patch to be worn by patients, the elderly, or eventually athletes. The nodes could measure temperature, heart rate, respiration, and other vital signs. The idea is not entirely new, but the design firm, Toumaz of the UK, says this is the first such system to be honestly disposable, and also claim it is much more convenient than the competition.

The "Sensium" SOC contains a wireless transceiver that runs on a few milliwatts. The chip also contains a processor, a temperature sensor, an interface for up to three vital-signs sensors, and signal-processing circuitry. The transceiver operates in the 862:870 megahertz (MHz) European Short-Range Device (SRD) frequency bands and the 902:928 MHz North American Industrial, Scientific and Medical (ISM) bands. Up to eight of the chips can share a single frequency, relaying their data to a base station in a hospital ward. The base station in turn relays the data to a central computer system.

The Sensium chip is powered by a multilayer printed zinc-based battery made by Power Paper of Israel. The battery is cheap, environmentally friendly, and can provide power for about five days -- by which time the patch is getting pretty grungy and needs to be replaced anyway. The ultimate target price for the chip is $5 USD in bulk buy. The chip is still undergoing evaluation and there's no target date for shipments.

BACK_TO_TOP* AUGMENTING REALITY: Computer-generated imagery to create "virtual worlds" such as elaborate videogames has become mundane, but as reported in THE ECONOMIST ("Reality, Only Better", 8 December 2007), computer graphics and data displays are now increasingly being used to enhance our view of the real world. Such "augmented reality (AR)" systems are mostly lab toys these days, but they are finding their way into the real world.

One application of AR that's already on the market is a system called "VeinViewer", now being sold by Luminetix, a medical-equipment firm in Memphis, Tennessee. One problem in medical procedures is identifying veins for drawing blood or performing injections. VeinViewer simplifies the work by bathing near-infrared light on a patient's skin: blood vessels absorb the light, allowing a digital camera to spot them up to a depth of a centimeter, and a projector then shines a map of the vessels onto the skin. Says one impressed user: "It's like Superman vision -- you can see under the skin." Comparable systems have been developed to assist surgeons; they provide a significant benefit to surgeons since there's no need to glance away from the patient. They haven't caught on yet, partly because of the learning curve for the surgeons, partly because of worries over malpractice suits.

There are less serious applications. YDreams, a digital media firm in Lisbon, Portugal, installed a "virtual sight-seeing viewer (VSS)" on a battlement of the 12-century Pinhel Castle in northeastern Portugal. This is no ordinary sight-seeing viewer scope; it gives an augmented and annotated view of the castle's elements, and even provides animations to show how the elements were constructed. In France, the Parc du Futuroscope, a theme park near Poitiers, is putting together a safari attraction in which visitors will ride a small train through a landscape, and spot "virtual animals" through AR binoculars.

There's been some interest in AR video games as well, though the pricetag is still too high for home use. The cost is expected to come down as applications spread and the technology matures. The military is investing development money into AR to move it along, with the Marine Corps now experimenting with an AR system in which recruits can move through a training area wearing goggles that superimpose various threats -- enemy armor, snipers, and so on -- on the landscape; instructors use tablet PCs to set up the threats and move them around. There is of course no reason that the same sort of technology can't be used in combat as well, allowing troops in the field to read "virtual" street signs, follow arrows designating patrol paths, identify known hazards as well as friendly forces, and so on.

Industrial applications are appearing as well. Volkswagen uses an AR system to check conformance to spec of incoming parts: the part is compared to its computer model and discrepancies are highlighted. The same process of comparing the model to the implementation can be used to check complete machines, implement production lines, and even entire plant facilities. Workers in factories can use AR to help them assemble products and check for discrepancies. AR is in its infancy just yet, but given its potential it may not be too long before it becomes yet another technology we can't do without.

BACK_TO_TOP* UNHAPPY ARABS: As reported in an article in THE ECONOMIST ("Between The Fitna, Fawda, & The Deep Blue Sea", 12 January 2008), Arabs are not generally a happy lot these days. The old have seen a lot of changes that few of them like. The young have received dull and inadequate educations. At home, rights are restricted; abroad, people think Arabs are all terrorists. There are few inspiring Arab leaders.

Of course, these are generalizations, there being a lot of diversity among the world's 300-million-odd Arabic speakers and the 22 countries of the Arab League. Some Arab states are doing well on oil money, and some are less repressive than others. However, the general mood over the Arab world is disgusted and doubtful.

Factors in the negative mood include skyrocketing population growth, bad public schools, the clash of tradition against modern urban lifestyles, and in particular politics. After World War II and the general end of Western colonialism, there was considerable optimism among Arabs that a renaissance of Arabic culture was at hand. The crushing defeat inflicted on the Arabs in the June 1967 Mideast war threw cold water on that belief, and the continually nagging problem of the Palestinians became an aggravation that would not go away. In fact, it's got much worse in recent years as the Palestinians have taken up sides, Fatah versus Hamas. How can other Arabs help the Palestinians if the Palestinians fight among themselves? Which side should Arabs support? Is it prudent or cowardly to seek compromise? Is it noble or hotheaded to go on fighting?

The situation in Iraq hasn't helped improve the sour Arab outlook, either. To be sure, for a time Arabs found the resistance against the American occupation heroic. It stopped seeming heroic when the focus of the fighting gradually turned from the invaders back to the ancient feud between Sunni and Shiite Islam. Most Arabs were appalled at bombings of markets full of defenseless women and children, nor were they generally pleased to see videos of decapitations of helpless hostages. Arabs still distrust the Americans and their "war on terror", seeing as more of a "war on Islam", but Arabs are also aware, sometimes from unpleasant personal experience, that "jihadis" are murdering more of their brothers and sisters than the infidels are.

There was a time when Arab citizens had inspiring leaders, like Egypt's Abdel Gamal Nasser and even, to an extent, Saddam Hussein, who were certainly flawed, but had a dream of progress and empowerment to sell. Nowdays, all the leadership is nondescript, with little international recognition or influence. To be sure, the end of the various "cults of personality" was not a bad thing in itself, since few want anything to do with the likes of Saddam Hussein any more. The problem is that it hasn't been accompanied by any real liberalization. Arab states go through the motions: they set up parliaments -- that end up being toothless or exclude real opposition; they create privatization programs -- that mostly benefit cronies; they drop formal censorship -- while passing broad laws against "spreading false information" and so on that force journalists to censor themselves. Voter turnouts are low, since everyone knows voting is a farce: less than 10% of Egyptians bothered to go to the polls in recent elections.

Some Arab states have been able to survive despite the lack of popular enthusiasm because they are propped up by oil money. The state may not be very effective, but the citizens aren't taxed heavily or at all, and so they tolerate it. There's also a general perception that a bad government is better than no government, with Arabs seeing the alternative to be "fitna" (communal strife) and "fawda" (chaos), as hideously demonstrated in Iraq.

Arabs have tended to fall back on tradition when things get rough, but tradition doesn't necessarily offer the best insights into how to deal with new realities. Women typically remain second-class citizens in Arab states; however much this is acceptable to Islamic societies, to the rest of the world it seems backwards, and even at home Arab women see empowered females elsewhere on DVD and satellite TV, generating cultural confusion. Similarly, the focus on tradition tends to promote xenophobia and reaction, not an interest in new ideas and ways of doing things. That hidebound mentality is reflected in a commonly-quoted statistic that more foreign literature is translated every year into Spanish than has been translated into Arabic for a millennium. The low quality of Arab schools similarly reflects this narrowness. A study performed by a university in Shanghai ranking the world's 500 best universities included one, repeat one, Arab university. The list included seven Israeli universities.

There are some flashes of light in the gloom. Some Arab states, such as Saudi Arabia, are trying to liberalize their educational systems. Birth rates are tapering off while, on the average, economic growth is good. Some Arab government officials claim that economic growth should help solve the Arab world's problems. That is hard to argue with, but it would help a lot more if it was accompanied by political and social reform.

BACK_TO_TOP* TECHNOLOGY & GOVERNMENT (2): One of the admitted success stories of e-government has been "i-government", the distribution of government information online. Under-30s cannot visualize what a pain it could be to get hold of a specific government form in the era before the world-wide web. These days, it's easy to get a form online. To be sure, the forms generally feed a bureaucratic system that runs by more or less the same rules as it did in pre-internet days, but just being able to get in the door without a great deal of hassle is a big improvement. More broadly, providing laws, regulations, congressional debates, and details of government budgets online can ensure greater transparency and more honest governance.

The US government's central i-government website, "usa.gov", is regarded as a model, providing comprehensive access to forms and government data, mostly through an extensive set of links to subsidiary sites, such as "benefits.gov" that provides detailed information on government benefit programs. Like any website of such scale implemented by a large organization, "usa.gov" has its problems -- broken links, useless pages, out-of-date information. Nobody is too surprised by such things, since anybody who's ever maintained a website knows how hard it is to ensure that every link works, and the more complicated the site, the harder it is.

Governments have a particular problem in setting up and maintaining websites. There are vast numbers of different agencies who are really the only ones qualified to provide valid information about their activities, but citizens don't want to have to wade through a balkanized set of webpages, and that means central coordination. The fact that there are citizens who are trying to use the system can get lost in this bureaucratic tug-of-war between the operational entities and central control. Britain's effort to centralize government information, "directgov", has been criticized for its haphazardness and lack of user-friendliness. The French government has done a better job, creating a central system that has been praised for its organization and design.

* There are now legions of consulting companies trying to help implement e-government. Their reports tend to be laden with jargon, but they tend to make the same central point, one that might seem to be obvious: that e-government has to be designed from the citizen's point of view, not the bureaucrat's.

Everyone also agrees in principle that e-government is a good thing. It means less hassle, less cost, less frustration, greater effectiveness; it also, in principle, means greater transparency, equating to less corruption and less incompetence going unnoticed. Alas, as noted, getting from here to there has proven difficult. Also as noted, Britain has been a significant example of how not to do things. The UK government had a program named "c-Nomis", which was to unify the hundreds of different databases uses in the criminal-justice system; it was recently scaled back significantly after its costs had more than doubled.

Some of the UK's e-government systems have made it online, with users then suggesting that it might have been better if they hadn't. Britain is working on a huge "Connecting For Health" program for the country's National Health Service (NHS) that is expected to cost about $25 billion USD in total. It is said to be the biggest non-military government software investment in the world. One element of the effort was "Choose & Book", in which patients could work with their doctors to select and schedule treatments. The system in practice is painfully slow, doesn't adequately cover patient problems, and can't be reliably used to set up appointments. Most users of the system have found it much more trouble than it's worth, though NHS brass say matters have improved, and believe it can be made to work.

An inefficient online system can be infuriating to work with. As the saying goes, computers don't argue, and when a problem crops up in a system -- for example, slapping the wrong citizen with a fine -- it can be a major pain to correct. There are also a lot of opportunities for things to go badly wrong. In November 2007, the British government had to embarrassingly admit that two data discs with unencrypted personal and financial details of 25 million UK households had been lost. Nobody liked the idea that their personal data might be in the hands of scamsters.

* Along with the problems in getting things to work right, there's the problem of figuring out if they're worthwhile even if when they do work. A 2002 Australian government survey of the economics of a set of the nation's e-government efforts found they cost about 8% more than they saved. What makes determining the economics of e-government particularly troublesome is that it is easy to figure out how much a program costs -- how much money was spent on computers, how much was paid to the software developers -- but it's not so easy to price out the actual benefits.

It is known that e-government efforts tend to add overhead if the old, manual systems have to be kept in operation alongside the new online systems. Since many citizens may not have online access, it's difficult to get around the duplication. Some countries, such as the UK and France, have been able to eliminate some duplication, mandating that all businesses handle taxes online, allowing the elimination of the old manual system.

Another issue in determining the economics of e-government is that it can have clear benefits that are hard to put a pricetag on. If e-government can be made to work smoothly, it means greater public confidence in government. A more effectively-run government also means a nation with greater international competitiveness. Yet another semi-intangible benefit is government encouragement of high-tech industries needed to support the systems, providing employment and also boosting international competitiveness.

* What is a little discouraging about the mixed grade report on e-government efforts so far is that the systems developed to date only cover the easy stuff -- obtaining forms, providing public information, and the like. All that's well and good, of course, but it's only scratching the surface of what could be done. Digging deeper promises very great benefits, and equally great risks. Given that the previous steps have not been entirely sure-footed, there is a lot of apprehension about taking the next big steps. [TO BE CONTINUED]

START | PREV | NEXT* INFRASTRUCTURE -- SHIPPING (3): Container ships are now the backbone of worldwide maritime freight shipment. The idea of putting cargo in containers and then hauling the containers on a freighter has a number of attractions, particularly in simplifying loading and unloading, as well as reducing cargo breakage and theft. The idea has been around for a long time, but it was held up because standardization proved troublesome: everyone's containers had to meet the same general specs to permit the scheme to be workable. If they weren't, they couldn't be stacked, and the gear to handle the containers wouldn't work with all of them.

The solution was developed in the 1950s by Malcolm McLean, who owned a trucking company. His container design was basically the trailer of a tractor-trailer rig without the undercarriage. McLean's bright idea was that the container could be mounted on a flatbed trailer for hauling down the road to port, where it would be lifted off the trailer and put on a container ship, with the process reversed at the destination end. Of course, as mentioned earlier in this series, the containers could also be hauled by rail. The first McLean container ship left port in 1956. It took about a decade for his scheme to catch on, but it has since become universal, with McLean's Sea-Land Corporation becoming a container industry giant.

McLean's original specification was a metal box 8 feet (2.44 meters) wide, 8 feet tall, and 10, 20, 30, or 40 feet (3, 6, 9, or 12 meters) long. The standard length increment meant that a space on a ship that could stow a 20-foot container could handle two 10-foot containers. A container ship's capacity is rated in the number of 20-foot containers it can handle, or "twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs)". Since not all cargoes can fit into standard containers, there are some oddball heights and lengths -- but overall, standards prevail.

Of course, all containers have a label or stencil to allow them to be identified and tracked. The label includes:

The container size and weight is also usually listed; the maximum possible container gross weight is 30.5 tonnes (67,200 pounds). There are specialized "tanker" containers for hauling liquids and pressurized gases, as well as refrigerated containers for hauling perishable goods. Not surprisingly, there is work on RFID and electronic locator / tracking systems for containers these days.

A container mounted on a flatbed tractor-trailer rig can be a bit difficult to tell from an ordinary tractor-trailer cargo hauler. The main recognition feature is that the container has fittings with holes in them on all eight corners, to allow it to be picked up by handling gear and also stacked up with other containers. When the containers are stacked, they're held together with twist-lock keys linked from the corner of one container to the matching corner of the other.

* Container ships are easy to recognize because their decks are covered with containers. Such vessels are not as long or wide as supertankers, but they tend to be tall. On a traditional container ship, containers are stacked four or five deep inside the holds, with the holds then sealed with watertight hatches and containers stacked four or five deep on deck. The latest container ships have no hatches, with the containers simply stacked up from the bottom of the hold. This makes loading and unloading easier, but it also means that the vessel tends to take on water rapidly in bad weather, and so the ship is fitted with powerful bilge pumps.

Such container ships are known as "lift-on lift-off (LOLO)" container ships. Some container ships that service ports lacking container handing gear are fitted with cranes to handle their own containers, but there's another option: "roll-on roll-off (RORO)" container ships, which actually carry trailers for tractor-trailer rigs, or even entire tractor-trailer rigs. There's also a specialized form of RORO freighter designed to deliver automobiles, with the biggest of them capable of carrying 6,000 cars on 13 decks. [TO BE CONTINUED]

START | PREV | NEXT* THINKING ABOUT CONSCIOUSNESS: I ran across a series of books by Oxford University Press titled VERY SHORT INTRODUCTIONS, and out of curiosity I picked up A VERY SHORT INTRODUCTION TO CONSCIOUSNESS by Susan Blackmore. I couldn't say I was entirely impressed by it, but it certainly did pose some interesting questions.

The first question is: what do we mean by "conscious"? Obviously we have much more awareness of our existence than, say, a brick, or for that matter a corpse, but attempts to define "consciousness" lead to endless argument. Even trying to think about our own consciousness is tricky, since the instant we do so, it influences our consciousness. This problem has been compared to trying to open a refrigerator door to see if the light is on.

We do have some fairly good ideas of what consciousness is not. Humans have what seems to be a nearly instinctive tendency to think of our consciousness as a "spirit" or "soul" inhabiting a meat body. This is referred to in consciousness research as "Cartesian duality", the idea being credited primarily to the classical French philosopher Rene Descartes. A cartoonish way of thinking of this is as a little person, an "inner self", in our heads who is observing the world outside through the "Cartesian theater" of our eyes and ears and other senses. Descartes believed the soul to reside in the pineal gland at the base of the brain.

The notion of Cartesian duality doesn't get much respect these days. The big problem is that it doesn't really explain anything: where does the inner self in my head get his consciousness? If we just proclaim it as some sort of magic, then why bother to invoke an inner self? Why not just claim consciousness is magical and cut out the middleman? Or do we claim consciousness is from another inner self at the next level? Is there yet another inner self below that level as well? And so on, more inner selves forever.

Cartesian duality ends up being an attempt to bypass the idea that consciousness is due to the normal operation of the brain -- and though we may not have a clear idea of how it happens, that position is far more defensible than the idea that consciousness is due to some sort of magic, or other unexplained and inexplicable process indistinguishable from magic. Psychoactive drugs can produce profound alterations of our consciousness, and unfortunate people with brain damage also have clearly altered consciousness, often in distinctly specific ways corresponding to damage of a particular component of the brain. Such evidence does not support the notion that our consciousness is independent in any way of the workings of our brain.

* The next question is of just how conscious we really are. We're all familiar with the sort of people who honestly believe their actions are always deliberate when they are predictably thoughtless and impulsive, and most people capable of reflection on their own conduct realize it's not always thought out. Although the notion that humans have instinctive behaviors tends to be criticized as promoting stereotypes -- which it certainly can -- it's hard to believe from much observation of the ordinary behavior of humans that their behavior isn't heavily influenced by instinct.

Even ignoring instinct, just how much of our brain activity is conscious? Consider driving a car across town, particularly on a route we often travel. Driving is a complicated and potentially dangerous procedure, but we can generally do so with near-perfect competence and safety without thinking much about it. What's consciously "going on" in the head during the drive? Maybe we're thinking about things we have to get done, maybe we're just woolgathering. Where's the real brainpower being used during the trip?

Similarly, anyone who's ever struggled with a difficult technical problem has had the experience of seeming to forget about it for a while, going to bed, and then waking up in the dark hours of the morning when the answer emerges in a flash of insight. Obviously the matter's been thought out in an unconscious fashion, with the conscious realization simply being a display of the results, the conclusion being quite useless if it isn't available for consideration. That leads to the question of whether consciousness serves any purpose at all in itself, some having suggested that consciousness is functionally irrelevant, a mere side-effect, what in evolutionary terms is called a "neutral feature" -- though this notion is regarded as extreme.

There is also the clear fact that we are not as aware as we think we are. We seem to perceive a world of enormous detail around us, but our eyes only have high resolution at the center, like viewing the world through a gunsight surrounded by a field of view of very coarse resolution. We build up a model of the outside world by scanning attention-getting details, with the brain filling in the scene. As stage magicians and makers of optical illusions know, the brain can easily fill in the scene incorrectly and it is not difficult to trick human senses.

To the extent that we are conscious, it is due to the sprawling networks of "pyramidal neurons" in our brain, which provide a "broadcast medium" for the brain's system of agents. It's been called "fame in the brain": one agent broadcasts to the other agents, which then decide on a course of action, if any, to be swiftly replaced by a broadcast from another agent.

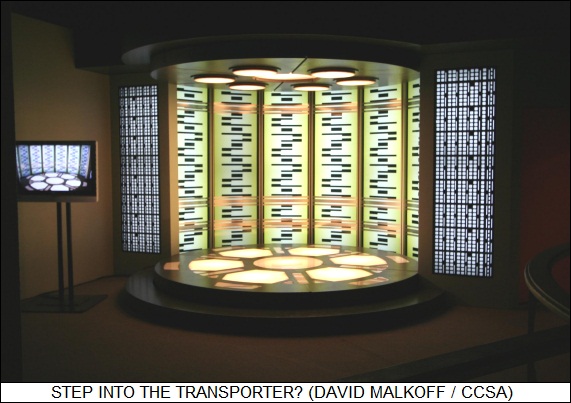

* Given a mechanistic concept of consciousness, we would be hard pressed to see it as anything more than the stream of consciousness, derived from organized neurological processes, backed up by our memories. This is flatly saying there is no "inner self", the notion is a fantasy. It is, however, a fantasy that humans have trouble letting go of. To illustrate, sci-fi series like STAR TREK like to envision a "matter transporter" in which Mr. Spock is scanned down to the atoms in a transmitter, with information produced by the scan sent to a receiver, where Spock is reconstructed. The trick is that the transmitter tears Spock to pieces down to the atoms; does that mean that Spock is dead, and that the Spock that walks out of the receiver is just a "clone"? The clone himself of course would not perceive the death of the original.

It might seem obvious that Spock dies, but even in our normal existence, the person we were a moment ago doesn't exist either, any more than does the Spock who was scanned by the transporter. We can argue that we do have a continuity of consciousness from the past to the present moment and into the future, but we go to sleep every now and then, or get put under general anesthetic. The continuity is broken, we sink into oblivion and revive later. We only live in the here and now, and the sense of continuity with the past and future is an illusion, supported by short-term memory.

* Finally, consider the question of whether animals are conscious. Descartes believed they were not, that lacking a soul they had no consciousness at all, being merely "meat machines". Few swallow this notion today, and in fact it's a bit hard not to think that Descartes had sacrificed sensibility to dogma. Anybody who's ever had a cat or dog knows they have distinct personalities and hardly seem machinelike. Certainly nobody but a sadist listening to an injured pet in severe pain can help but empathize with it. There are obviously things going on in the human head that nobody believes can happen in the mind of an animal -- working out math problems for example -- but it's hard to buy that there's a discontinuous gap between the minds of humans and the minds of animals.

The other side of this question is whether a machine can ever be conscious. There's another interesting thought experiment that provides some insight into this issue. Consider the notion of a person who is what might be called a "zombie", who functions by all appearances as a normal human being, but has no consciousness. The first question in this scenario is: how could we distinguish a zombie from the rest of us? By definition, we can't. By the same coin, how could any one of us know that he or she is the only conscious human and the rest of us aren't zombies?

This sounds absurd, and the American philosopher Daniel Dennett has suggested that it is. According to Dennett, any being that is capable of conducting itself as perfectly human will be as conscious as any other human. Dennett does not believe this simply as an operational assumption: If we can't tell the difference, we might as well not worry about it. What Dennett points out is that if we see a perfectly normal human in action and try claim that this person is a zombie, then we have to ask: What is that person functionally missing?

From an evolutionary point of view, consciousness would have to be judged to have evolved to support specific behaviors to enhance the survival and propagation of the human species; any element of consciousness that doesn't support such useful behaviors is evolutionarily irrelevant. By the reverse logic, if a particular entity has all the behaviors, the consciousness underlying that behavior would seem to be necessarily there as well. What is the magic "something extra" the zombie is supposed to be lacking?

Dennett's reasoning is hard to dismiss: if we don't see consciousness as an inescapable result of intelligence, then we have to judge it a functionless side effect. If it is, then we could imagine biological or machine intelligences that are just as smart as we are, indeed vastly smarter, but that aren't conscious. If so, then they might well wonder why we make such a fuss about consciousness -- but if they weren't conscious, how could they wonder about anything? How could they "think things over?"

In any case, by Dennett's thinking, if we create a machine that can conduct itself like a human, then it will be as conscious as any human. The interesting item is that if we did create such a machine, we would be able to then simply ask it: "Are you conscious?" If it answers "yes", we would have very little alternative to accepting that answer as the truth. We would not be able to design the machine to be conscious, since we don't know how we would, and if anyone were to cheat, that would be quickly revealed by inspection of their code.

There isn't any other test for consciousness except to ask, any more than we could know if a person prefers chocolate to vanilla ice cream, or likes or dislikes both, except by asking. To pose the question: "What do you think about that?" -- is just a specific case of the meta-question: "Do you think?" It's actually hard to see any real objection that could be raised to such a test. Do we believe that a dog is conscious? Most of us do, because it acts like it is. If a machine acts like it's conscious, why would we not believe it is as well? We can't ask a dog if it's conscious, we still think it is; we could actually ask the machine, and if it said YES, it is hard to see how any constructive objection could be raised, or why anyone would want to try.

The difficulty with the question of consciousness is that it is not clear the question makes real sense. If we accept the idea that consciousness is merely the experience of being an intelligence -- at least a functionally human-like one -- then consciousness is an uninteresting consideration in itself, though it leaves open the big questions of what precisely is meant by "human-like", and how to build a machine that behaves in such a fashion.

That's not trivial, but the alternative is hopeless: to claim that consciousness is due to some unexplained phenomena that we cannot describe in any specifics; nor propose any way of tracking down, even in principle; while being completely unable to give any reason why that it should be so, other than vacuous incredulity. That amounts to no more than manufacturing problems for one's self, and leaves nothing useful to discuss.

BACK_TO_TOP* BUILD A BETTER DUMPER: ECONOMIST.com was proud to present a report from a correspondent who attended the World Toilet Summit in Delhi. Toilets may be an unsavory subject, but they are also important from the point of view of the environment, public health, and simple personal convenience. Many of the world's poor have lavatory facilities that are inadequate in all three of these regards, and that was the issue the Toilet Summit was organized to address.

The UN's Millennium Development Program includes among its goals providing proper lavatory access to all the world by 2025. This is a considerable challenge, since 2.6 billion people don't have proper facilities at present, leading to inadequate disposal of hundreds of billions of tonnes of human waste. The biggest challenges for meeting the goal of proper lavatory services for all are money and water -- there is clearly not enough of either to go round to do the job. Most towns in India do not have sewage systems, and Indian families cannot afford a septic tank, so those are not realistic options over the short run. Most of the demonstration technologies shown at the Toilet Summit focused on using solar heat to accelerate the natural decomposition of human waste.

One such demonstrator -- presented by the Sulabh International Social Service Organization (SISSO), an Indian nongovernmental organization -- is already in use in thousands of public facilities. It features a shallow toilet bowl that can be washed clean with two liters of water, a fifth that used by an ordinary flush toilet. The toilet empties into one or two cesspits, which are rotated once every three or four years. The unused cesspit can be allowed to stand and dry out, with its contents then used as fertilizer.

The decay of human wastes does release methane, a potent greenhouse gas. Most of the methane produced in the cesspits is absorbed into the soil, but some of SISSO's larger facilities have biogas digesters that allow the methane to be used for fuel, to be burned into water and carbon dioxide, a far less potent greenhouse gas. A biodigestion facility does require at least 300 flushes a day to be cost-effective. However, SISSO calculates that a public lavatory with 2,000 users a day would produce 60 cubic meters of gas that could be used to run a 10 kW generator eight hours a day, enough to keep the lavatory lit up. The organization's biggest lavatory complex, near a Hindu pilgrimage site near Mumbai, produces a surplus of methane, which SISSO is promoting as a cooking fuel. Work is underway on means of gas storage and distribution.

SISSO is also linking waste-water treatment to aquaculture, growing duckweed in domestic waste-water, and then fattening fish on the duckweed. The output water is useful for fertilizer. There are of course health concerns over raising fish using sewage as an ultimate feedstock, but advocates believe that such issues can be dealt with.

BACK_TO_TOP* COUNTING NOSES: Trying to obtain statistics on the public can be controversial, and as reported in an article in THE ECONOMIST ("Census Sensitivity", 17 December 2007), public statistics don't come any more sensitive than they do with a census.

There is nothing new about taking a census: Biblical rulers did so, though when David, King of Israel, ordered a census a plague struck the land, killing tens of thousands. David had to atone for his sin, and the fiasco helped give the procedure a bad name from then on. In 1634, John Winthrop -- governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony -- chose to estimate the population of his domain, explaining to a correspondent: "David's example stickles somewhat with us." When a Census Bill was debated in the British Parliament in 1753, there were warnings that performing a census would result in riots.

The real problem with a census was actually public suspicion, not divine wrath. The trouble was that a census was traditionally about war and taxes: it helped to know the structure of the population to levy taxes, and it helped to fight a war if there was information on how many warm bodies could be obtained to fight it. Since census information could also be used to determine the defensive capabilities of a country, census data was sometimes a state secret.

However, as societies became more elaborate, the need for information expanded beyond war and taxes. Following the London plague of 1603, weekly bills of mortality were published, listing the deaths in the city; from 1629, the causes of death were listed as well. Such data was obviously useful for public health measures, and began what would become a detailed craft of the statistical analysis of public data. In 1731, Benjamin Franklin began to publish data on the comings and goings of vessels at ports in the northern American colonies in his PENNSYLVANIA GAZETTE, the goal being to estimate the level of commerce.

Later, the creation of the new United States of America led to pressures to perform a comprehensive census to make sure that each state was allocated its proper number of Congressmen in the House of Representatives; of course, that meant that a census had to be performed periodically to adjust representation as populations increased. The first American census was performed in 1790, and it was something of an innovation, mostly because it was the first census to be mandated in a national constitution. The exercise went well -- no plague was visited on America, or at least not one that was out of the ordinary -- and other countries began to get the census bug as well.

Once people were inclined to sort through this kind of data, all sorts of interesting patterns popped out. In the 19th century, two French statisticians, Andre-Michel Guerry and Adolphe Quetelet, analyzed statistics on crime and were astounded to see how predictable crimes were on a statistical basis. They could estimate how many forgers would get caught, how many murders would occur, and so on, with Quetelet suggesting that there was no such thing as free will, a notion now mocked as "statistical determinism" -- a certain number of people in a society were going to be murderers, and there was absolutely nothing that could be done about it. Nobody accepts such fatalism now, believing instead that such statistics should be used to help zero in on problems and reduce their impact. That is partly due to the work of Florence Nightingale, who tended to the wounds of British soldiers during the Crimean War. She is remembered as an "angel of mercy" by most of the public; statisticians also honor her as one of the founding figures of statistical analysis in health and other public services, with her meticulous and elegant graphs outlining the causes of death among soldiers under treatment to show the authorities what needed to be done.

* A census is now a normal procedure of a modern state. In 1995, the United Nations (UN) asked all member states to hold a census within a decade to provide data for UN decision-making. However, a census can still be a sensitive matter. The Germans are very touchy about a census, because all know how the Nazis used census data to round up "undesireables" and put them in concentration camps. When new questions were added to a German census in the 1980s, there was a uproar and the courts struck them down, citing a conflict with a "right of informational self-determination." Germany is planning a census in 2011, the first since reunification, but it will be a sampling, not a full census; identification data will not be retained, and questions will not be asked on religion and ethnicity.

In authoritarian states, a census can be unwelcome and blatantly intrusive. China performed a census in 2000; it asked somewhat nosy questions, such as: "How often do you bathe?" -- but what really made people apprehensive were questions designed to see if people were violating the "one-child" rule, having more kids than they were allowed.

In a more open society like the USA, instead of people worried about being counted, they tend to worry about not being counted. The more people in a particular interest group -- ethnic groups, religious groups, the homeless, whatever -- the more social clout that group has. That means that there is pressure on census takers to ensure that surveys are meticulous and correct to prevent undercounting. In the UK, church leaders were gratified that the 2001 census showed that 70% of Britons called themselves Christian, boosting the influence of churches in British society. However, that figure also highlighted the tendency of census questions to mislead, since church-attendance figures suggested the bulk of those Christians only attended church once a year at most. It is not easy to create a valid public survey, since their results are very sensitive to the way the questions are posed, and of course they compress attitudes that may be very subtle and highly varied to short lists of simple questions.

Misleading though such statistics may be, British gays and lesbians were disappointed when it was announced that the next UK census in 2011 would not ask about sexual orientation -- it wasn't that government statisticians didn't want to know, it was just that nobody could figure out a formula for asking for that kind of information that didn't offend some people and confuse others. Illustrating the problem, the Metropolitan Police in the UK conducted a survey on sexual orientation and got as the most common response: "What is heterosexuality?"

That gays and lesbians wanted to be counted was a testimony to the basic tolerance of British society. Minorities living there might not agree with that notion, but tolerance is a relative concept, as the difficulties of performing a census in nations with deep social divisions shows. Nigeria hasn't had an uncontested census since the nation's independence in 1960 -- too much social chaos, too much incompetence. There's much at stake, since the census helps divide up the country's oil money, but that leads to quarreling. In the most recent census, in 2006, leaders in the Muslim north insisted that questions on tribe and religion not be asked; leaders in the Christian south demanded that they be included. The results were of course contested.

The shakier the state, the more hassles there are over a census. Trying to perform a census in Iraq is obviously troublesome; Lebanon, with a government apportioned between quarrelsome religious factions, hasn't had a census since 1932 because too many people in power fear it would upset the status quo, which is unstable enough already. In a really mad state, a census can be nightmarish. In 1936, Josef Stalin told his census takers that the census to take place in 1937 would show the population of the Soviet Union in 1937 would be 170 million souls. The officials apparently didn't understand that he was not venturing a guess, he was giving them an order. When the census takers came back with a population of 162 million and added unwelcome data, such as the fact that at least half of Soviet citizens still believed in God, they were either imprisoned or shot. In the 1939 census, the replacement group of census takers got much the same results -- but wisely classified them as state secrets and declared that the population of the USSR was, of course, 170 million people.

BACK_TO_TOP* TECHNOLOGY & GOVERNMENT (1): THE ECONOMIST is fond of publishing extended surveys on a range of subjects, and the 16 February 2008 issue featured a survey titled "The Electronic Bureaucrat" (by Edward Lucas -- they're about the only materials in the magazine that have an author with a real name), concerning government through technology, or "e-government".

The survey starts out with a closeup, concerning Britons trying to get visas from two foreign embassies in London. At the Indian embassy, applicants have to stand in line, usually from the dark hours of the morning. All the effort has to be done in person, they have to pay in cash, they have to fill out all the forms by hand, they have to submit a printed photo for the visa. The procedure is pretty much the same as it was in the 1950s. Compared to the other aspects of taking a trip to India, for example lining up hotels and airfares on the internet, the whole matter seems ridiculously antiquated.

At the fortresslike US embassy in London, applicants still have to get in line to get a visa, but they make their application and payment online, obtaining by email a printout with a barcode that they take to the embassy. On entry, the barcode is scanned, digital fingerprints are taken, and a visa is promptly printed out. The visa itself has banknote-like security features.

* It has been said that dealing with a government is like kicking a one-ton sponge, but as this story shows, technology can help reduce the size of the sponge considerably. The story has another side, however, since in the cases of both embassies, applicants are still subjected to ridiculously intrusive questions that almost encourage them to lie, all the more so because the questions are usually unverifiable and unverified. Technology can streamline a system, but it does not change its goals -- and if the goals are hidebound and bureaucratic, so is the system, no matter how much technology is applied.

Governments are trying to obtain leverage off of technology to improve their interactions with the citizenry. They have made some progress with "i-government", the online distribution of forms and other information. The internet is also being used to share data between government departments, though there are privacy concerns over this, and so non-citizens tend to be more roughly handled in the process than the citizens. In the wings is the delivery of services online, what is called "m-government" -- for example, providing a visa that can be downloaded into a smart card or mobile phone -- and "e-democracy", linking the offices of politicians with the voters.

To create effective e-government, governments will have to be able, at least to a degree, to compete technically with the online systems of internet giants like Amazon.com. The e-government systems will have to be as easy to use; they will have to personalize their interactions, recording data on each user and tailoring the transactions accordingly; they will have to be running all day, every day. However, there are limits to how much an e-government operation can imitate Amazon.com, since the missions and roles of governments are very different from those of businesses. People generally want to buy something from Amazon.com, while a driver's license is something they are legally forced to get whether they like it or not.

E-government is a promising new frontier, and governments in wealthy countries regard it as a high priority. Massive sums have been pumped into it, though so far the results have been mixed. The problem is that government is so inherently complicated and conflicted. There are debates over what government should and can deliver; how the effectiveness of delivery can be measured; what trade-offs there are between government efficiency and citizen rights; and what trade-offs there are between citizen rights and public security. It's not surprising that hammering out workable systems has been troublesome. [TO BE CONTINUED]

NEXT* INFRASTRUCTURE -- SHIPPING (2): The classic notion of a freighter is the "break-bulk" freighter, in which various cargoes are loaded individually or on pallets. These days, break-bulk freighters have generally been replaced by container ships, though break-bulk freighters do still service smaller ports where there are no container handling facilities. Such freighters carry their own loading and unloading facilities, traditionally being fitted with derricks, consisting of a boom hung from a central post. Derricks are effective but a bit tricky to operate, so more modern break-bulk freighters use cranes.

The cargo is loaded into a break-bulk freighter's hold through deck hatches, which may be as big as a tennis court. The hatch openings have waist-high raised sides, called "combings", to help keep out water; the hatches are "battened" with bolts or heavy clamps. Placing the cargo, incidentally, requires a bit of planning lest the load become unbalanced and make the vessel prone to capsizing. A "loadmaster" plans out the proper distribution of the cargo.

A traditional freighter had a "three-island" structure, with a "forecastle" or "foc'sl" at the front, a "bridge" in the middle, and a "poop" in the front. The seamen lived in the forecastle, engineering officers lived in the bridge (the engines were generally just below), and the officers lived in the poop. Modern merchantmen are more automated and have smaller crews, so there is only one island, a deckhouse / bridge structure, usually at the stern, where everybody lives.

* Some commodities, such as ore or grain, are shipped in such great quantities that it makes sense to build freighters dedicated to carrying them. Such vessels generally look like break-bulk freighters, but without the derricks or cranes; dock facilities handle loading and unloading. In the case of ore freighters, the ore is dumped into the hold directly from railroad hopper cars, and removed at the destination by scoops or other excavators. Grain can also be loaded from hopper cars, but it's removed by suction hoses. Incidentally, while it doesn't take a lot of planning to distribute the weight properly on a bulk carrier, loading up the bulk material requires some caution, since simply dumping it in on one side might well cause the vessel to capsize at dock.

Of course, oil is a form of bulk commodity, and the "supertankers" that haul it are famous for their size, with such vessels in some cases bigger than aircraft carriers. As mentioned earlier in this series, supertankers are so big that it's hard to find ports that can handle them, and so in many cases the oil is offloaded to smaller tankers for ultimate delivery, a process called "lightering". Incidentally, the transfers take place with both vessels under power, since they are more controllable than they would be if they were at anchor.

A tanker is mostly empty space, with a deckhouse / bridge at the stern, where the engines and the pumps used to load or unload the oil are placed as well. The hold is divided into sets of tanks, with at least five dividers lengthwise and at least three across the beam. The hold is divided into separate tanks to permit hauling different oil products; to prevent dangerous sloshing in heavy seas; and to limit losses in case the tanker is holed. There are pipes on deck to access each tank, switched to a connecting header. Loads can be transferred through a big flexible hose, or through a swiveling pipe "hard arm".

A heavy electrical cord is attached from the ship to shore when transferring fuel -- this is a grounding strap to prevent electrical sparks from literally raising hell. Fire is unsurprisingly a major hazard on a tanker; it has been commented that all tankers seem to be named NO SMOKING. The danger is not so much from the cargo itself, but from the fumes from the cargo that accumulate in the empty space or "ullage" at the top of the tanks, which can light up explosively. To reduce this hazard, the tanks are topped off with inert gas filtered from the ship's engine exhaust.

Tankers are infamous for oil spills, but for a long time they were causing major pollution problems just in normal operation. When coming back after a delivery, the tanks were filled with sea water as ballast, and the water was also used to clean the nasty sludge or "clingage" left by the oil out of the tanks. In 1973, laws were passed to require separate tanks for oil and ballast. Procedures were developed to use oil itself to wash out the clingage, which also ensured that more product was delivered to the refinery. Laws were later passed to require tankers to have a double hull to give them more protection in case of an accident.

Of course, a tanker has its own supply of bunker fuel, and doesn't use any of the product it's carrying. This is because the tanker company doesn't own the cargo, it belongs to oil companies, and the bunker oil that the tanker burns is less valuable than the crude, being little more than refinery waste.

Despite the size of supertankers, they have small crews. Crews used to be about 30, now it's more like half that. The navigation officers have to mount round-the-clock shifts, but the "mechanics" that keep the ship running can operate on an eight-to-five basis. In port, the crew loads or unloads and then returns to sea. Tankers are very slow, and so the voyages are long and monotonous. Given that any source of excitement in such an environment is likely to be unwelcome, there's something to be said for boredom. [TO BE CONTINUED]

START | PREV | NEXT* ANOTHER PROBLEM WITH ETHANOL: The race towards biofuels has not been without its critics, particularly of corn-based ethanol, with claims that it produces only marginally more energy than that put in to synthesize it, and that biofuel production is squeezing corn supplies, making food prices rise dramatically. Now, according to an article in THE ECONOMIST ("Don't Mix", 1 March 2008), ethanol production has another strike against it: water usage.

City authorities in Tampa, Florida, were a bit startled when they got a request from US Envirofuels, a company building Florida's first ethanol production plant, for 1.5 million liters (400,000 US gallons) of municipal water a day to support the plant. This would make the plant one of the city's ten biggest water users, and long-range plans envisioned that the plant would eventually double in size. Since Florida is in the middle of a long drought, nobody was able to figure out where the water was going to come from.

The number of biofuel plants in the USA has risen from 50 to about 140 over the last eight years, and about 60 more are under construction. The Federal government wants biofuel production to expand fivefold by 2022. However, as one think-tank put it, "water could be the Achilles heel" of ethanol. Ethanol production is heavily dependent on water, which is used in the boiling and cooling components of the distillation process. Residents in several states are taking legal action to block ethanol plants being built that tap local aquifers.

One bit of good news is that ethanol plants have cut their water usage in half over the last decade, and some believe they can cut their usage in half again, mostly by using "closed loop" processes where the water is continuously recycled. However, as one industry expert puts it: "There are things you can close-loop and things you can't."

* TOXIC CFLS: We now live in an era of energy-technology revolution -- and like all revolutions, things don't necessarily happen the way people would like them to. As another case in point, SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN had a brief article ("Toxic Bulbs" by David Appell, October 2007) on compact fluorescent lightbulbs (CFLs), the energy-efficient bulbs that are gradually replacing the old incandescent lightbulbs.

CFLs are marvels of technology, using only a quarter of the power of incandescents and lasting an order of magnitude longer. However, they have a problem: they contain mercury. About two billion CFLs were sold in the USA in 2007, which at about five milligrams of mercury per bulb equates to ten tonnes of mercury to be ultimately dealt with. Manufacturers have been able to reduce the amount of mercury, but haven't figured out a replacement for it.

The answer over the long term is probably energy-efficient LED lighting, but over the short run there's a need to recycle CFLs. The recycling rate in the USA is only about 24% at present, with the procedures and regulations for recycling being very inconsistent. Sylvania offers a send-back kit for a dollar; it's hard to think it's very popular. Walmart is more practically setting up recycling kiosks their stores, but for the moment only in California. The US Postal Service is considering a recycling program that could establish a national standard. Until something like that happens, however, CFL recycling by consumers is going to remain haphazard. [ED: As of 2022, CFLs are out of business, replaced by LEDs. It is still possible to find places to dispose of them.]

BACK_TO_TOP* ELECTRIC DRIVE FOR SHIPS & PLANES: The idea of propelling a naval vessel with electric motors is not new: the classic diesel-electric submarine runs on electric motors driven by banks of batteries when submerged, with diesel engines providing propulsion on the surface and charging up the batteries by running the electric motors in reverse. However, while surface warships were experimentally fitted with a "hybrid" system using combustion engines and electric motors as far back as 1912, the idea didn't catch on: it was fuel-economical but too complicated.

According to an article in THE ECONOMIST ("Making Waves", 8 December 2007), that's now poised to change. The main driver for "going electric" is that modern warships have a lot of high-power electronic systems, such as long-range radars and big banks of computer processors, and electric power for such systems can account for as much as 30% of the fuel use on a warship. The power demand is clearly going to get more severe in the future as navies begin to deploy electric-drive railguns and directed-energy weapons on their vessels. Once the shipboard electric power system gets that big, there's no good reason not to go all-electric and be done with it.

The main technology enablers for electric-drive ships are modern power electronics and digital power control systems, which can reliably and easily shunt as much power as needed to whatever system required. Electric drives can be distributed around a ship, making the propulsion system less vulnerable to battle damage; in addition, electric drives allows one propulsion unit to be repaired while others stay online. The hybrid system is more fuel-efficient than direct drive by diesel or turbine engines, simply because a combustion engine is only efficient at a narrow range of speeds; in a hybrid system, the combustion element operates at a constant speed to run a generator system, which not only makes the combustion engine more efficient, it permits it to be simpler and lighter. The British Royal Navy's new Type 45 destroyer, being designed with a hybrid system, will have four engines, and when on a slow cruise it will only use one of them. Fuel economies are seen as running in the range of 10% to 25%.

Hybrid systems are showing up on commercial vessels as well. The ocean liner QUEEN MARY 2, at the time of its launch in 2003 the biggest ocean liner in the world, uses a hybrid drive, with a power system that could supply electricity for a city of 700,000. During the day, the drive runs air-conditioning, theaters, and other systems; at night, it propels the ship at high speed to the next port of call. At least 4% of liquefied natural gas tankers now being launched are hybrids. The US Navy has performed research into electric motors using coils made of high-temperature superconductors; not only would such motors be more efficient, they would only weigh a third as much, more than compensating for the need for a cooling system.

* There's also the possibility of hybrid aircraft. Aircraft are already using an increasing amount of electricity, with airliners having elaborate entertainment systems for passengers and combat aircraft carrying a lot of high-power electronics gear. The use of electricity is likely to increase further as reliable electric motors gradually replace traditionally more powerful but less reliable pneumatic and hydraulic actuators. Work is being performed on jet engines with high-power electric generators as an integral component, not just a tack-on accessory, to provide the power needed for directed-energy weapons and the like.

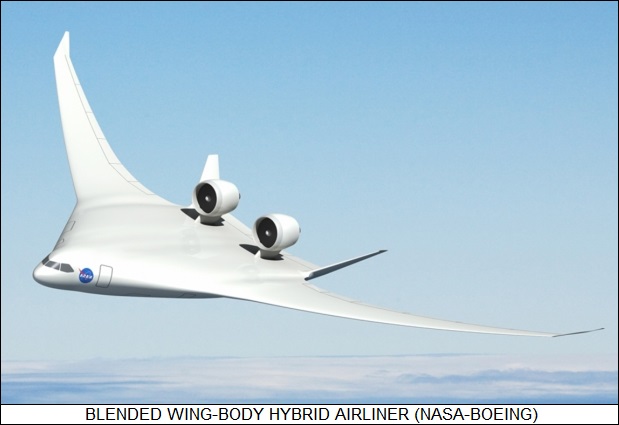

Then there's the option of the all-electric propeller aircraft. Small drones are already available that run on lithium batteries driving efficient, lightweight motors. It does get more difficult to use an electric drive system as the aircraft gets bigger, since an electric drive system is heavier than a jet engine system with the same propulsive thrust. However, new "blended-wing-body (BWB)" aircraft designs -- basically a variation on the classic flying wing, giving an aircraft reminiscent of a manta ray -- are very aerodynamically efficient, meaning the weight penalty might become more tolerable.

Imagine a BWB with a bank of fuel cells or a combustion turbine mounted amidships, driving sets of superconducting motors turning props or ducted fans. We've got so used to piston and turbine propulsion for aircraft that the idea of using electric drive seems all but unbelievable; but maybe a few decades from now, we might not think twice about flying the electric skies.

BACK_TO_TOP* HARNESSING BRAIN POWER: Anyone who spends much time online knows about the little tests websites use to ensure that a real human is performing a transaction and not some netbot, in which the user is asked to type in a unique codephrase displayed in a graphic with skewed letters and numbers. Such a test is called a "Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers & Humans Apart" -- or blessedly "captcha" for short.

As reported in an article in WIRED ("The Human Advantage", by Clive Thompson, July 2007), captchas were invented in 2000 by Luis von Ahn, a professor of computer science at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He grew up in Guatemala City, the son of two doctors, who told him they didn't care what he did as long as he didn't become a doctor. He liked to tinker with computers and ended up getting a computer science doctorate from CMU, which has one of the world's most prestigious computer science departments. Von Ahn came up with captchas while working for his doctoral thesis, and no time at all they became a standard technology, throwing a spanner into the works of obnoxious netbots that had been previously running wild.

Captchas were enough to give von Ahn a superstar reputation, at least among the computer geek community, but he didn't want to stop there. He got to thinking about how much computing horsepower there was in the human "meat computer" between the ears; almost anybody could deal with a captcha that stopped computer character-recognition software cold. He got to wondering how this brainpower could be exploited.

One interesting problem was indexing the vast quantities of images available on the internet. An image search involves a user typing in a text description of a desired image, with images matching the text description returned for inspection. Not surprisingly, getting a close match between the search text and the images returned is troublesome, all the more so because by default, the only thing the search engine can do is scan the web page containing an image in hopes that text surrounding the image provides some descriptive information on the image. This is not always the case. What if, von Ahn thought, there was some way to encourage users to provide useful indexing text for images that would make them easier to search for? Search engine operations like Google would kill for such a capability.

Von Ahn figured out that he could get people to contribute brainpower by handing them an intriguing game -- after all, people spend large amounts of time playing games online without worrying about payment, and if he could give them a game that was enough fun, plenty of enthusiastic worker bees would show up. He cobbled together a quick prototype that he titled the "ESP Game", which involved two randomly-chosen online users presented with the same image. Each would try to enter keywords describing the image, with points awarded when the two users provided matched keywords. Such matched keywords were likely to be good index keys for the image, much better than those a search engine could extract from textual context.

Much to his surprise, von Ahn's ESP Game became a big hit through word-of-mouth, overloading his server. The index keywords produced by the game were far more accurate than those of existing search engines: a Google image search on "dog" gave dogs in only two-thirds of the images, but the indexing provided by the ESP Game had very few misses. He made a pitch to Google brass in December 2005, and they were sold, introducing a production version in August 2006 as the "Google Image Labeler".

* Von Ahn realized that he was on to something, and since then he has developed a number of other work-as-play games:

Building games is not easy, as von Ahn admits; it's certainly not the sort of thing academics are trained to do, so he has recruited help from game designers. He says: "Game design is a very funny thing. There are people out there who are really good at it, but it's not clear that they can teach it. It's a very intuitive process. It's an art." Along with the games his team has introduced, many more have been scrapped since they're just not fun to play.

* Von Ahn hasn't forgotten about his first claim to fame, captchas, while he's working on games. He's got a strong cryptology bent, and as any good cryptologist knows, any lock that can be built can be broken one way or another. Spammers have gone to the trouble of hiring third-world workers to crack captchas, but he doesn't worry about that much, since the rewards for spamming are too low to make such an approach profitable. The real problem is the emergence of character-recognition software that can crack captchas.